The rise and fall of an Afghan strongman

Leaders of armed groups have infiltrated Afghanistan’s fragile education system.

Ghor, Afghanistan – After three years of studying international law in India, Fakhrudin Sharyar Shark was certain he would get himself a plush job when he came home to Afghanistan.

But he was returning to Ghor, the impoverished central province where members of illegal armed groups outnumber Afghan National Police forces by almost five to one.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsThirty years waiting for a house: South Africa’s ‘backyard’ dwellers

Photos: Malnutrition threatens future Afghan generations

From prisoner to president in 20 days, Senegal’s Diomaye Faye takes office

Many of the country’s large employers most often looked to by recent graduates – foreign businesses, international NGOs and government ministries – are either under the control of armed groups or simply do not exist in Ghor.

Sharyar returned to Ghor in July 2012, aged 25, confident that his bachelor’s degree would gain him a high-ranking government position. The province of Ghor, after all, could only boast an 18.5 percent basic literacy rate, according to the ministry of education.

Within days of his arrival, he turned to Sema Joyenda – one of Ghor’s six representatives in the Afghan parliament – asking her to put in a good word for him with provincial governor Abdullah Hewad.

Sharyar had his eye on the position of deputy governor.

Joyenda told Al Jazeera the young man who had been so bold as to approach her was “talented and intelligent”.

Clearly impressed with his ambitions, Joyenda promised Sharyar she would do what she could – despite a reportedly fractious relationship with the governor.

But even with his academic qualifications, she advised him to gain some experience and work his way up. Disappointed that his expectations could not be met immediately, the impassioned young man soon grew impatient.

Taking up arms

Situated on the infamous drug-smuggling route from northern Faryab to southwestern Helmand, and home to a bustling arms trade, Ghor afforded Sharyar little opportunity to make use of his degree in international law.

As his dreams of joining the ranks of senior civil servants crumbled, he sought a leadership role in a different form of rapidly growing organisation – he picked up a gun, joining the ranks of 6,500 other young men in Ghor.

Sharyar soon led one of the province’s 130-plus illegal armed groups.

|

| The road from Kabul to Khor was closed down for three days [Obaid Ali/Al Jazeera] |

Over the course of nine short months, he earned a reputation for harassment and exploitation. Extortion became Sharyar’s chief means of income.

The man who could not find a job months prior was soon employing barely educated Ghoris as his foot soldiers who asserted his dominance over the district of Dawlatyar.

With 65 percent of Ghoris classified as either jobless or making meagre wages, Sharyar had no shortage of men to choose from.

For three days in May, Sharyar closed down the road between Kabul and Ghor, in search of a young boy and girl who had run away together. While disapproving of the young couple’s actions, the community was not pleased to have the main road blocked by an aspiring strongman.

Later that month, Sharyar and his men held a 90-minute standoff with a rival leader – when Sharyar demanded wheat and money from the people of Dawlatyar.

Political support

Shams ul-Rahman, a Dawlatyar resident, told Al Jazeera that there were several formal complaints lodged against Sharyar and his men, but little had been done to stop them.

Despite a much-feared reputation among the people, Sharyar continued to earn the support of Ghor’s political representatives in Kabul.

When he was killed on May 19, there was relief in the community and outrage among the political elite.

Ghor parliamentarians, incensed at Sharyar’s death after a prolonged gunfight between his group and the Afghan National Police, took the case to the Upper House of the Afghan parliament. There were discusssions – but soon the entire matter was dismissed.

The police here maintain that Sharyar was little more than a strongman quickly rising up in the ranks.

“Does a civil society activist lead armed groups elsewhere in the world?” asked Delawar Shah Delawari, the provincial chief of police.

Joyenda, the parliamentarian Sharyar had turned to months previously, said his death was an unacceptable targeted killing.

“If they really wanted to capture him, why didn’t they go after him two days before – when he had personally gone to see the governor?” Joyenda asked.

”The

10 uneducated people.”]

That Sharyar was the only person killed – despite a fierce firefight – is something which fuels more of Joyenda’s doubts.

In the impoverished province, Joyenda told Al Jazeera Sharyar’s death was a particularly heavy blow.

“The killing of even one literate person is more painful than [that of] 10 uneducated people,” she told Al Jazeera.

Joyenda, who described Sharyar as “utterly intelligent”, accused the police of misplaced priorities:

“If the police chief wants to bring security to Ghor, why not address those who take up arms ten kilometres from the police compound? Why target him?”

Joyenda was referring to armed men who, on the periphery of the Afghan government-controlled area, have organised locals, in order to exert control over an estimated 70 percent of the mountainous province.

But Sharyar’s story is anything but rare in Ghor.

The arms trade and drug trafficking industry have created a cycle that has allowed illegally armed groups to infiltrate all aspects of life in the province of 650,000 residents.

In 2011, the relocation of five district-level courts to Chaghcharan, the capital, was cancelled due to the lack of security. The residents of Charsadda, Du Lyna, Pasaband, Saghar and Shahrak districts said this only strengthened the grip of local commanders.

Beyond threats of insecurity, these illegally armed groups also hamper personal lives.

In a March 2011 IWPR investigation, police, government officials and local residents reported several cases of leaders of armed groups abducting, abusing and selling off local women.

These reports came a year after a video surfaced of two women in Du Lyna district being publicly flogged by the order of Fazl Ahad, another local strongman, for running away from their abusive husbands.

The instability and insecurity combined, bred by this hostile atmosphere, has affected everything from business to construction and education in Ghor.

“At the very least, you need a Kalashnikov at home to feel a sense of comfort,” one villager told Al Jazeera.

Education

In Ghor, where the shadows of strongmen loom large, every institution – even schools – have become party to the power struggles between rival factions.

|

|

| Schoolgirls in Herat speak of the importance of education |

The Lycee Gardelang, located in the capital of Du Layna district, has become yet another battleground for rival commanders. Here, Nasrallah and Mahmoud fight for control of the district’s 47,000 residents.

In an attempted show of strength, each commander approached education ministry officials to have the only boys’ high school in the district capital staffed by teachers loyal to them.

This has made local residents hesitant to send their children to the school, where they say madrasa-trained mullahs have replaced many of the former teachers.

Of the 42 schools in Du Layna district, only seven teachers are professionally trained educators, the rest, like in Lycee Gardelang, are mostly religious teachers, who are handpicked and rewarded for their loyalty to leaders of local armed groups.

Anjela Sharefi, a women’s rights activist and provincial council member, told Al Jazeera that in most villages, strongmen and tribal elders prevent schools from functioning unless they are able to appoint the teachers directly.

“When our children go to school, the teachers give more homework than instruction,” one local resident told Al Jazeera.

Many parents throughout the central province shared similar sentiments, saying the attitude of teachers was one of: “I can only teach you what I know. What I don’t know you will have to go find out elsewhere.”

When locals do step in to fill in the shortage of qualified teachers, the results are not much better.

In the empty yard of the Arzbegi village mosque, 35km outside Chaghcharan, an 18-year-old teacher standing in front of a blackboard admits to having no education training.

It was the double-digit unemployment and a teacher shortage that led him to teach Afghan history.

Asked who killed Nadir Shah, the former king of Afghanistan in the 1930s, the young teacher responded: “I don’t know. It could be one of these armed groups, I guess.”

It was a student named Abdul Khaliq who assassinated the former king, at a high school prize-giving ceremony.

For many Ghoris, a profound lack of faith in the province’s education system has convinced them that their children’s time would be better spent in other pursuits.

Though unqualified for his job, the young man was the only person – student or teacher – present at the school that day. “Everyone else [including the two other teachers] went off to a wedding,” he told Al Jazeera. “It’s just me.”

With the frigid winter approaching, many families will soon dispatch their children to collect firewood in preparation for the heavy snowfall that will leave much of the province largely inaccessible for up to four months.

With these strongmen holding sway over local education officials, it’s not just the quality of instruction, but also the physical structures of schools, which have suffered.

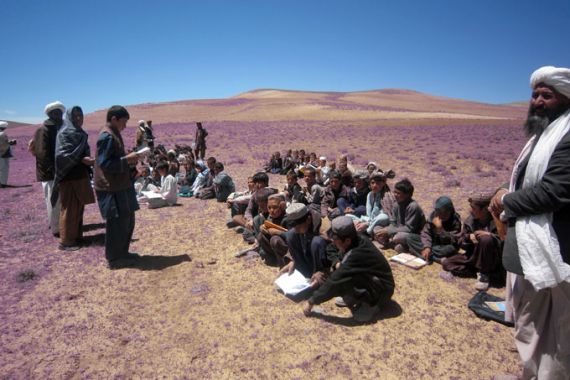

Only 10 of the 42 schools in the southern district of Du Layna are housed in permanent structures. The others consist of makeshift gatherings in fields and in UN-funded tents, Districy School Governor Khawja Hossein Daneshyar told Al Jazeera.

Mohammad Hassan Hakimi, a civil society activist based in Chaghcharan, reveals an “open secret” that illustrates the control these armed leaders have on the provincial department of education.

Though official documents list 30 to 40 teachers employed in each school, Hakimi told Al Jazeera that, in reality, the majority of schools are staffed by only a handful of teachers. The phantom teachers, said Hakimi, help to “line the pockets of the strongmen”, who claim the salaries of the non-existent educators for themselves.

Indeed, the local branch of the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission says 50 to 60 percent of the province’s 814 schools are closed – while the “teachers” continue to receive salaries.

Perhaps this was precisely the kind of situation Sharyar had thought his foreign education would distance him from.

Instead, for many in his home village of Shina, Sharyar was only perpetuating the system he had maybe hoped to rise above.

Obaid Ali is a researcher at the Afghanistan Analysts Network, where he has written extensively about Ghor.

Follow Obaid Ali and Ali Latifi on Twitter.