Brazil’s Syrians divided on Bashar al-Assad

With Syria embroiled in civil conflict, immigrant community in Sao Paulo is at odds over support for the ruling regime.

Sao Paulo, Brazil – The ornate conference room looks like what you might expect to find in an office of a top government minister in Syria: Comfortable chairs neatly organised around an oval, perfectly polished oak table, tasteful pieces of Arab art lining the walls, and long drapes over the windows. Directly in the centre, at eye level, is a framed photo of stoic-looking Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

But this is not Damascus, rather the view from inside Club Homs, a decades-old social club rooted and named after the first group of Syrian immigrants to Brazil.

Club Homs sits on busy Avenida Paulista – one of the busiest streets in Sao Paulo. But with its discreet and simple lettering in front, the club is easy to walk right past without noticing.

The club is a symbol of the first group of 400 Syrian immigrants – all from Homs and most Christians – who came to Brazil at the invitation of Brazilian emperor Dom Pedro II, ruler from 1831-1889, a worldly globetrotter who spoke Arabic among multiple other languages.

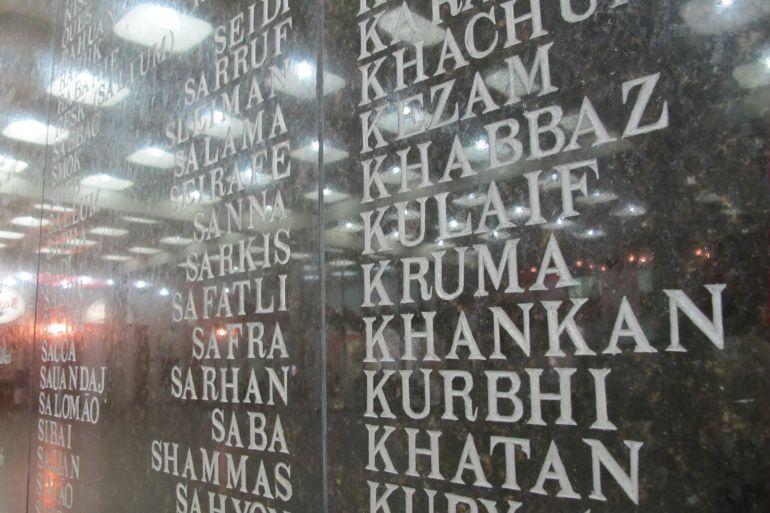

Today look around Sao Paulo and symbols of Syrian influence are evident in the Hospital Sirio-Libanes (Syrian-Lebanese Hospital), the Syrian Arab Republic Viaduct, the Syrian Orthodox Cathedral, the Esporte Clube Sirio (Syrian Sports Club), not to mention dozens of shops and restaurants downtown run by Syrians.

|

| Club Homs, the social club on busy Avenidua Paulista in Sao Paulo. [Gabriel Elizondo/Al Jazeera] |

There are no exact statistics, but it’s generally accepted there are about four million people in Brazil who are citizens or descendents of Syria, according to Tammam Daaboul, a Syrian writer in Sao Paulo who runs arabesq.com.br

With Syria embroiled in escalating civil conflict, those in Sao Paulo find themselves largely divided, just like their homeland.

On one side there is Eduardo Elias, a descendant from Syria, a longtime member of Club Homs and current president of the Federation of Arab Entities in Brazil.

Elias is deeply troubled by the conflict in Syria, but stands behind al-Assad.

“I think it’s my obligation, as a son of a Syrian immigrant,” Elias said. “I swore to my father that I would always defend Syria, and I always will. This conflict cannot continue. What is happening in Syria is foreign fighters that are attacking and it’s also Syrians that are not thinking of their country, only power and politics.”

As Elias sits in the conference room at Club Homs, he enjoys telling stories of his more than two dozen trips back to Syria, and showing photographs of himself with al-Assad and his wife Asma when they visited Brazil in 2010.

“When Assad came here to Sao Paulo, he made a speech, and he gave us a big responsibility,” Elias remembers. “He said, ‘each one of you is an ambassador to Syria, be good citizens to make Syria bigger.’ I had a private conversation with him, and it didn’t seem to me that he was evil or the devil that everyone now is making him out to be.”

Different points of view

But on the other side of the city, in a small house in a working class neighbourhood, the view is very different.

That is where Amer Masarani, a Syrian who has lived in Sao Paulo for 15 years, is hunched over his desktop computer updating the anti-Assad Facebook page he manages that also serves as a support network for Syrian refugees in Brazil.

This year there have been 90 requests with Brazilian immigration authorities by Syrians looking for refugee status. Thirty-four have been granted, and the others still being evaluated.

Once Syrians arrive in Brazil, one of the first people they call is Masarani.

|

| Amer Masarani, a Syrian who has lived in Sao Paulo 15 years, runs an website that helps Syrian refugees in Brazil. [Gabriel Elizondo/Al Jazeera] |

“We are receiving refugees here who bring their kids who are now so traumatised by what they have seen and heard in Syria,” Masarani told Al Jazeera.

“There is one child, only two years old, who just came from Syria with the parents, and when there is an explosion or a balloon pops they cry and go under the table thinking it is shooting.

“And I see these pictures of dead children. What did they do? Are they to blame for their own death because their father doesn’t want Assad in power? Assad is killing his own people. He is the worst dictator ever.”

On a recent evening at Masarani’s house, there are six other immigrants from Syria, one of whom, Jehad Mohamed, recently fled when some of his family members were arrested and tortured by al-Assad security forces, he says.

‘I can’t go back, and they can’t leave’

In another neighborhood of Sao Paulo there is Ahmed, a young Syrian who served two and a half years in the army in his country. He asked that his real name not be used in fear of repercussions.

Ahmed has lived in Sao Paulo for one year, and is fearful to return to his homeland because he’s still a reserve in the Syrian army. He says he would certainly be called up to fight with al-Assad forces, something he said he won’t do because he is against the regime.

He’s worried about his mother and other family back home, but they are too afraid to leave in fear of something happening to their home while away and then losing everything.

“I can’t go back, and they can’t leave,” Ahmed said matter of factly. “It’s all so complicated.”

The uncertainty with the Syrian community in Brazil can be traced back to a generation divide, according to Daaboul, the Syrian writer.

“The group that supports the Assad government in Brazil is born from fear and worries that Syria could turn into an Islamic state, which could harm the interests of the Christians, most of whom are the early immigrants to Brazil,” Daaboul said. “The opposition to Assad is coming from recent immigrants who know more about the current socio-political situation, and who don’t believe the argument about sectarian violence.”

All sides do share two things in common, namely, a genuine love for their homeland, and a frustration in watching from so far away as it spirals into further violence.

“Everyone is praying for this to be over soon,” Elias said, pausing and taking a deep breath before adding, “But I personally think it will go on for a long time.”

Follow Gabriel Elizondo on Twitter @elizondogabriel