An education in conflict

In conflict-affected states, children are being left behind by state and private schooling networks.

|

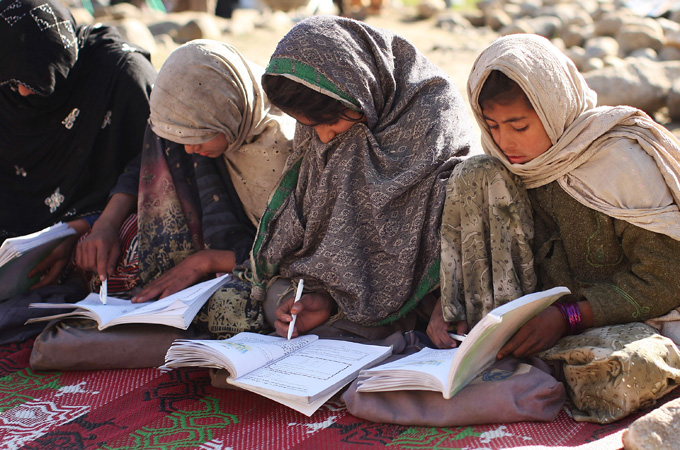

| One in three children in conflict-affected fragile states do not go to school [GALLO/GETTY] |

Despite widespread commitments on paper to the second Millennium Development Goal – the provision of universal primary education by 2015 – 72 million children remain out of school. More worryingly, 39 million (54 per cent) of these children reside in conflict-affected fragile states (CAFS), where they face multiple pressures in terms of lack of access to basic rights, and an accompanying unwillingness on the part of international donors or even local governments to place an emphasis on providing education.

As a result, one in three children in CAFS do not go to school, compared to one in 11 in other low-income countries, according to data compiled by the UK-based charity Save the Children (STC).

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘We share with rats’: Neglect, empty promises for S African hostel-dwellers

Thirty years waiting for a house: South Africa’s ‘backyard’ dwellers

Photos: Malnutrition threatens future Afghan generations

“It is obviously practically difficult, both logistically and in terms of safety for students and staff,” says Tove Romsaas Wang, the head of STC’s worldwide Rewrite the Future (RTF) campaign, which aims to prove that primary education can be provided even in the difficult circumstances presented in CAFS.

“But our starting point is that every child, whether you live in a conflict area or not, has the same right to education.

“Conflicts today may last 10 or maybe 30 years – if you don’t provide education in conflict situations, you may miss out on five or six generations of primary school children.”

Decimated teaching force

Undertaken in 2006, the RTC campaign has so far reached more than 10 million children in 20 countries – mainly located in Asia and Africa, and including Angola, Afghanistan, Haiti, Cote d’ Ivoire, Southern Sudan and Uganda. Its aim is to both increase enrolment and improve the quality of education in CAFS, in partnership with local ministries of education, through a combination of direct investment of aid and pressuring governments to live up to aid commitments.

RTF is funded through a combination of national, private and corporate donors, the more significant of which include Australia, Canada, Denmark, the Netherlands, the UK, the US, the EC, the UN, UNICEF, the World Bank, Accenture, ExxonMobil Foundation and Ikea.

There are several challenges when it comes to delivering education in areas which are either experiencing conflict, or where conflict has recently ended, according to John Gregg, the director of the Qatar-based Education Above All NGO and strategic planner at the office of Her Highness Sheikha Mozah Bint Nasser Al Missned of Qatar. With active hostilities, he said, logistics can be a challenge, but the lack of teachers can often be of even greater concern.

“Often the first wave of violence will actively target the elite, and this includes teachers – either as pro-government figures, or as community leaders. So you get situations where your actual teaching force has been decimated by the conflict.”

Exacerbating existing barriers

But the lack of teachers in these areas, while a key concern, is simply the tip of the iceberg.

In areas where conflicts are either ongoing or recently concluded, it is often a serious logistical challenge to build new school structures, deliver school materials – such as textbooks, desks and writing materials – or revise curricula if need be. Moreover, in CAFS, the conflict often exacerbates existing barriers such as poverty, lack of infrastructure and discrimination in admissions policies – both economic and otherwise.

The RTF approach, Wang said, is that the actual school building itself is secondary – teaching may happen “in someone’s home, or even under a tree”. But while the teaching can occur in makeshift spaces, what is important, she added, is to ensure that the education that is being delivered is of a high quality.

To this end, RTF’s approach focuses on training teachers, helping communities rebuild their schools and providing school materials.

“One of our key learnings [sic] was that when we manage to work very closely with the community, and the community takes ownership of the school, [it] is likely to succeed,” she stressed. In this respect, STC is better placed than many other international actors, according to Wang, because of the charity’s long-term presence in these states. “We have been in these countries for years. So this allows us to build trust with local communities, networks and actors.”

From the ground up

But having a context-driven, flexible approach to each state is simply not enough. Resources, as ever, remain an abiding problem.

While CAFS represent 60 per cent of the current annual funding requirements for education – which stands at $16.2bn – only about 10 per cent of what they need is being committed to them, and even less actually gets to them.

“Often the priority for those who want to respond [to conflicts or emergencies],” said Gregg, “is in a physical thing. So, for instance, they say ‘I want to build 70 schools’.

“Okay, that’s very nice, but where are the teachers for the 70 schools, where are the desks, where are the books? How about the teacher training, or the psycho-social support for both students and teachers?

“Donors often get concerned about giving money in fragile environments, so they’d rather invest in something concrete.”

The data reveal a telling picture. As CAFS tend to also be low-income countries, comparing their expenditure on education with other low-income countries is a useful indicator. While other low-income countries devote an average of 16.9 per cent of government expenditure to education, CAFS spend just 13.5 per cent, even though their needs may be far greater, given that in many cases they have to rebuild education systems from the ground up.

Funding shortfall

This shortfall in local expenditure means that foreign donors become particularly relevant in the case of CAFS. The 2010 UNESCO Education For All Global Monitoring Report estimated that CAFS require $9.8bn in education aid. The actual amount committed, however, remains a paltry $1bn, of which less than 12 per cent ($113mn) has actually been delivered.

The issue is not just that there is a funding shortfall, but the way that global education aid is structured. Not only is the aid tied to government’s domestic concerns (which have seen aid commitments from countries such as the UK, Canada and the World Bank actually decrease), but more than half of CAFS aid went to just five countries – Afghanistan, Pakistan, Ethiopia, Nigeria and Uganda.

Analysts say that this is often because these countries have a more well-proven ‘track record’ when it comes to aid, and also because delivery of aid to CAFS can often occur in unpredictable circumstances.

Wang, for example, pointed out that many donors would be unwilling to invest in building schools in ongoing conflict zones because there is no guarantee that the building will not be destroyed.

She asserted that this was a particularly unhelpful approach, as the structure itself was simply a starting point for aid, and that it can still be invested in many other, intangible education assets – such as teacher training or funding support for local ministries of education.

Furthermore, with the lack of coordination in aid into conflict zones, education often falls into the gaps between humanitarian and development aid, with pre-crisis levels perhaps supporting education, but emergency and post-crisis aid neglecting adequate investments in education.

‘Superficial’ measures

Finally, much of the aid coming in from national donors, according to Gregg, is often tied to very “narrowly defined government policy” outcomes. These measures may look good, but they can be very “superficial”.

Gregg pointed to the Millennium Development Goal itself as an example of this: “It’s a very shallow measure, really. Getting children into school is one thing, but is what they’re getting at the school equipping them for life? Is it a quality education? That’s a huge question that we’re not measuring. So sometimes some of the things we set ourselves as a goal or intent as a donor […] are a little bit superficial.”

Barriers remain high and funding scarce, but Wang said: “I think we have made the point that it is possible to deliver education in CAFS. When we deliver results, that will generate funding, as it is unrealistic to expect donors to invest without a model for success to follow.”

And the effect is showing, with the Netherlands and Spain both increasing their level of committed and delivered aid. The funding shortfalls, however, remain, and with education aid levels actually dropping between 2007 and 2008, it is clear that these are contingent upon domestic political realities.

With the world financial crisis, innovative financing options now need to be developed to allow money to continue to flow in in a manner that builds sustainable systems. Steen Jorgensen, the World Bank’s sector head of human development in the Middle East North Africa region, for example, has called for the development of a ‘human capital’ market, to be run along the same lines as the carbon market.

In the meantime, children in CAFS continue to face poorly resourced schooling systems, where governments remain either unable or unwilling to make the necessary investments to provide them with access to primary and secondary education, and barriers such as poverty, lack of teachers and lack of quality education continue to exist.

With these 39 million voices out of the net, the Millennium Development Goal remains a tool for rhetoric, in both possibilities for attainment, and, perhaps, even content.