In Pictures

The battle for Beirut’s skyline

Activists struggle to save what remains of Beirut’s architectural heritage.

Beirut, Lebanon – Following the chaos and destruction of the Lebanese civil war, the battle for Beirut’s skyline has endowed Lebanon’s capital with a schizophrenic urban landscape: modern luxury apartment blocks tower over crumbling Ottoman mansions, cranes pick at construction sites next to overgrown abandoned plots of land.

Civil activists have long lamented the government’s lack of concern over preserving Beirut’s architectural heritage, accusing it of prioritising lucrative real estate deals over the more expensive task of conserving the remaining Ottoman and French mandate-era buildings across the city.

The most recent statistic from 2013 showed that 80 percent of the buildings, originally listed as historical landmarks after the war ended in 1990, have since been destroyed.

Yet calls by NGOs such as Save Beirut Heritage and the Association for the Protection of Lebanese Heritage for the state to spend more money and time on the issue have largely fallen on deaf ears.

Instead, the task of keeping such houses from ruin and demolition has fallen to individuals and non-state actors.

Luckily, many have risen to the task.

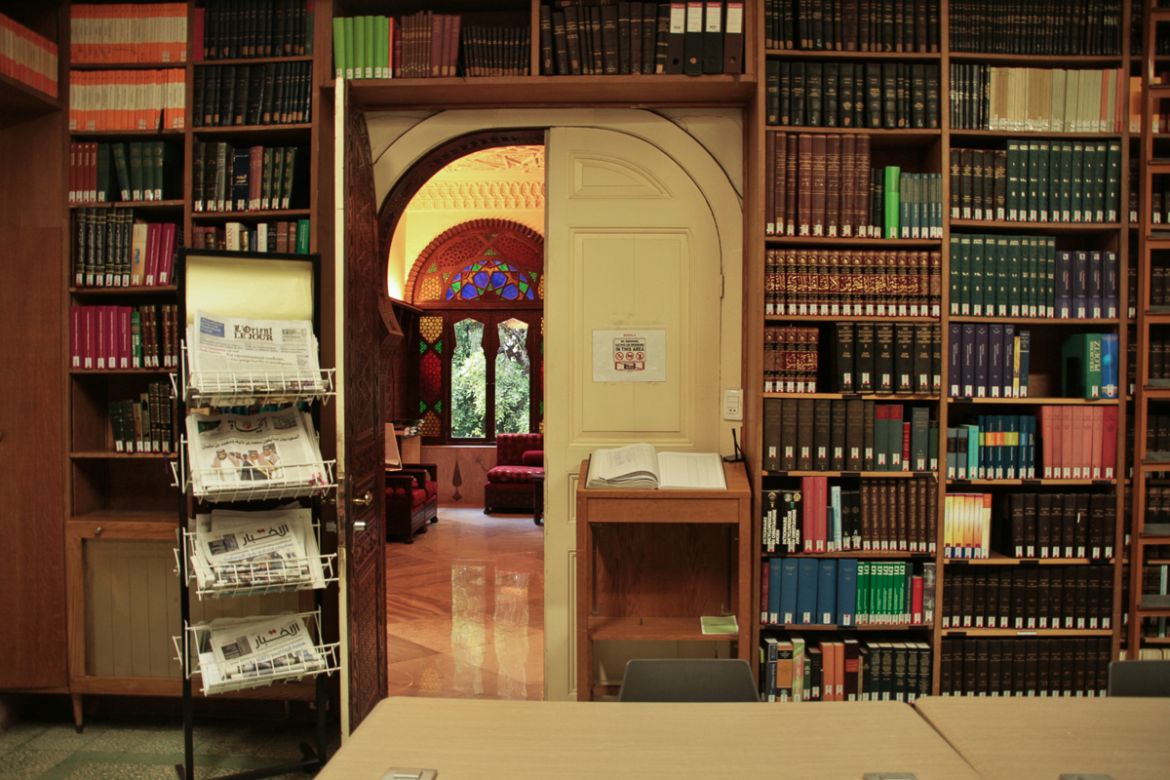

From spaces for performances, art exhibitions, and NGOs, to hotels, cafes and even an academic research institute, Beirut’s enchanting old houses are increasingly being given a new lease on life and new purposes, and as a result, being preserved and opened up for all to enjoy.