Action urged to avoid social chaos

ILO chief tells Al Jazeera migrant workers to be among hardest hit by economic crisis.

|

| The global economic crisis has serious implications for migrant workers across the world [AFP] |

The International Labour Organisation has predicted that the global economic downturn could see up to 50 million people lose their jobs in 2009.

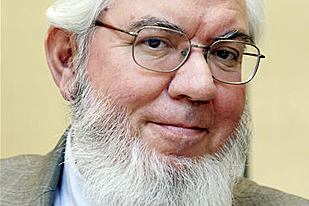

Juan Somavia, the director-general of the ILO, answers questions about the full implications of the crisis and what can be done to relieve it.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsA flash flood and a quiet sale highlight India’s Sikkim’s hydro problems

Why is Germany maintaining economic ties with China?

Behind India’s Manipur conflict: A tale of drugs, armed groups and politics

Al Jazeera: What should the G20 summit focus on?

Somavia: Above all they need to agree on how to solve the credit crunch which is paralysing investment, trade and consumption. At the same time, the summit should give priority consideration to the need to address the jobs crisis and social protection for people and families.

Beyond this, we need a new governance system based on the four normative pillars of finance, trade, labour and environment. They need to be mutually supportive as a foundation for a fair globalisation that is inclusive, sustainable and produces equitable results for everybody. We need a new basis for a charter for coherent and sustainable economic governance.

Filling the global policy and institutional vacuum is key. This was the main subject of a meeting last week called by Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, with the heads of the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the World Trade Organisation, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the ILO to discuss how to work together better to foster recovery and establish a stronger, cleaner, fairer economy.

Nicolas Sarkozy, the French president, and Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero, Spain’s prime minister, have already called on the tripartite ILO to participate in the formulation of new global governance institutions.

Italy, currently chairing the G-8, has emphasised the importance of the ILO’s role in dealing with the social dimension of the crisis. Lord Mark Malloch-Brown, the British minister for the United Nations, is coming to the ILO on March 4 to present a first-hand view of preparations for the London summit.

How does this crisis measure up to unemployment crises of the past, and does it have wider-reaching implications globally than previous crises?

In 2009 the recession will lead to a dramatic increase in unemployment in developed countries and in working poverty/vulnerable employment in developing countries.

The ILO estimates that in 2009 open unemployment may increase by between 30 and 50 million people in comparison with 2007, reaching a total of 230 million, a global unemployment rate of 7.1 per cent.

The number of working poor in developing countries could increase by as much as 200 million. If so this will take the world back to poverty levels of 1997, wiping out nearly all the gains of the past decade. It will all depend on successful recovery policies being implemented.

We must not forget that before this financial crisis there was already a major socioeconomic crisis, with continuing massive poverty, under-employment, growth in inequality and difficult social conditions for large segments of the world’s population, in both developing and developed economies.

The benefits of globalisation had not been widely or fairly shared and the backlash was already there. For many, this was globalisation without a moral compass, which the financial crisis confirmed.

There is a growing sense that globalisation has become unfair and unbalanced with inequality growing. That no one was providing thoughtful guidance and oversight. That no one seemed to be in charge. This became evident when the financial crisis erupted.

As a result, the share of wages in Gross Domestic Product has gone down almost everywhere. In many countries consumption had been stimulated on the basis of increasing personal debt. Now governments are desperately trying to stimulate consumption – when in fact if higher productivity had been transferred into higher wages, demand would be also higher today.

Everything we know about past economic crises, from the Great Depression to the Asian financial crisis in 1997, indicates that their social impact will be deep and long lasting: job losses; declining incomes, wages and purchasing power; social spending affected; houses lost; deferred new investment; slowing international trade: in sum, progress in poverty reduction backsliding and middle classes worldwide weakened.

The highest price will be paid by the weakest and more vulnerable segments of society. There is fear that the economic downturn and looming recession will turn into a social recession. This process has already begun.

Which countries are likely to be the worst hit?

Compared with 2007, the largest increase in a regional unemployment rate was observed in the Developed Economies & European Union region, from 5.7 to 6.4 per cent. Here the number of unemployed persons jumped by 3.5 million in one year, reaching 32.3 million in 2008.

|

| Juan Somavia is calling for decent work creation [AP] |

In North America, the economy of the United States shrank at its fastest pace in 26 years in the last quarter of 2008. In the Eurozone (EU 16) the rate of unemployment climbed to 8 per cent in December.

We know that the effects of the crisis will continue to expand in developed and developing countries, but in the latter, we must remember that many people do not have the opportunity to move into “unemployment”, with the social protection that developed countries attach to that term.

So in this sense the worst hit countries will be those which do not have sound systems to ensure the most vulnerable have some form of protection to fall back on as well as those countries depending heavily on foreign direct investment, external remittances, international trade and tourism.

Countries with sound banking systems, larger internal markets, high saving practices and strong reserves will have more resources and space to weather the crisis. But everybody will be affected.

What trends are we likely to see emerge from rising unemployment?

There is a significant risk of a prolonged labour market recession. The long-term unemployed may have considerable difficulty obtaining new employment. Some people who lose their jobs, notably women and older workers, may be pushed out of the labour market altogether.

Such trends are not easily reversed even if the economy recovers. Young people who leave school will have a more difficult start in the labour market. This is not only a social tragedy, but also represents a waste of human capital.

Will there be greater social unrest?

The current economic squeeze is provoking tensions and risks to social stability. As we all know the first signs are already there, there is a huge popular frustration brewing.

We will have to be extremely vigilant about a resurgence of social tensions in a context of economic distress, with added risks of discrimination, victimisation of trade union representatives and protectionist economic policies that would only aggravate the crisis.

We must all be sensitive to the fact that this crisis is affecting countries, enterprises and workers who have no responsibility whatsoever for its origin. Policies must protect workers and small enterprises world wide – these being the most affected.

What will the impact be for migrant workers?

The current global financial and economic crisis has serious implications for migrant workers worldwide.

Past experience makes us painfully aware that migrant workers, especially women workers and those in irregular status, are among the hardest hit and most vulnerable during crisis situations.

While the full impact of the crisis on migrant workers is yet to unfold, there are reports of direct layoffs, worsening working conditions including wage cuts, increasing returns, and reductions in immigrant intakes. Source countries are already grappling with the challenge of employment creation for their citizens including increasing numbers of return migrants and falling remittances.

I believe countries should put this issue in their bilateral and multilateral agendas. Managing the many dimensions of the problem is possible – but you need to address them before they get out of hand.

Could the crisis lead to greater exploitation as demand for jobs increases or companies struggle to stay afloat?

Workers who have jobs may become scared and accept wage cuts or worsening employment conditions. As a result, the crisis gets worse: the prospect of lower incomes and the risk of higher unemployment reduce confidence, affect consumption, and further aggravate production and employment.

As I have said, progress in poverty reduction is unravelling and middle classes worldwide are weakening.

Inequality not only leads to a decline in productivity but breeds poverty, social instability and even conflict. There is evidence that excessive income inequalities can be associated with lower life-expectancy and educational performance in the case of the poor countries, with malnutrition and an increased likelihood of children being taken out of school in order to work.

What can governments do to tackle rising unemployment, and are they currently doing enough?

For years now the ILO has been calling for a new globalisation model centred on decent work creation, not financial speculation; on a balance between government, markets and society. It is unfortunate to see, once again, that it takes such a deep crisis to prompt leaders in business and governments into action. I welcome such action.

The ILO message is realistic, not alarmist. We are now facing a global jobs crisis. Governments are aware and acting, they are trying to stop this steep decline with massive bail outs of the banks where necessary, as well as other measures. However, more decisive and coordinated international action, particularly on job creation and social protection, is needed to avert a global social recession.

Last November, the ILO was one of the first international institutions to propose a global approach. The Officers of the ILO’s governing body, (representing governments, employers and workers) have highlighted six priority policy actions: ensuring the flow of credit and stimulating demand; extending social protection, training and retraining opportunities, and other employment policies, with particular focus on the vulnerable – young women and men, workers in precarious employment, and migrant workers; supporting productive sustainable enterprises, particularly small enterprises and cooperatives; employment-intensive investment and green jobs; ensuring that fundamental principles and rights at work are not undermined and that respect for decent labour standards is promoted; strong cooperation between the ILO and the multilateral system, and deepening social dialogue and tripartism; and maintaining and expanding development aid and other investment flows to vulnerable countries.

I would add that the crisis should be used as an opportunity to make the economy more socially and environmentally sustainable. The short-term responses to the crisis should therefore pave the way for a fairer and greener economic growth model.

How long could it take for unemployment rates to start falling again?

It is unclear when this crisis will bottom out and when we will see signs of recovery. All forecasts available today are rather pessimistic. What we do know is that recovery from social recession is much slower than financial or economic recovery. Unemployment goes up like an elevator and comes down only slowly through the stairways, during which time valuable skills and motivation are lost.

More fundamentally, it may take just a few months for the crisis to jeopardise the gains made over the past 15 years or so with respect to tackling working poverty and promoting social inclusion.

It is important to pave the way for a better economic model, which avoids the excesses, instability and inequalities created by the present one – a model that gives much greater attention to employment and social protection.

The prospects depend crucially on the policy response to the crisis. Lack of coordination would be particularly harmful, as it would considerably reduce the effectiveness of stimulus packages.

From where I stand it appears that the crisis underscores clearly a vacuum in global governance. We have no comprehensive agreement on what policies are required to get us out of this crisis, and remember this is global, no country is immune.

Individual countries and regions must come together around a global and comprehensive set of policies that respond to the deep uncertainties of individuals, families and communities. Fortunately, the G20 have taken the lead and first steps. Action must then be followed up in the pertinent international organisations.

What measures can be taken to stop another financial crisis such as this one?

We must deal together with the immediate crisis and the crisis before the crisis. The ILO has been an advocate for a fair globalisation, a fair deal, providing opportunities to all. We believe a reformatted globalisation can deliver this, but some changes need to be made to the present model. Now is the time to do this.

Building a new system will require a reassertion of universal human values such as those expressed in the ILO’s constitution, and our declarations on fundamental principles and rights at work and on social justice for a fair globalisation.

If a large number of countries would decisively advance towards decent work and a sustainable environment, with a new global governance, then globalisation would be very different.