Realising the Zionist dream

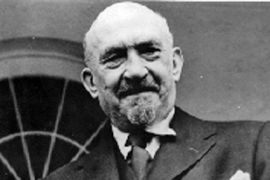

Chaim Weizmann became the first president of Israel.

|

| Chaim Weizmann, right, nurtured relations with US President Truman, left |

To the more scientifically-minded, Chaim Weizmann may be considered the father of industrial fermentation but to most he is known as the first president of the fledgling state of Israel and contender – along with Theodor Herzl – to the more controversial crown, the father of Zionism.

As unrelated as his scientific and political careers may appear, it was in fact the former that brought him to the attention of high-ranking British government officials, gaining him the contacts and influence he would utilise so effectively to establish the latter.

But the story began far from either England or Palestine, in the small town of Motol in the Pale of Settlement – the part of Russia to which Jews were largely confined.

It was there that Weizmann was born to an observant Jewish family in 1874 and began his formal Jewish education when he was just three years old.

Weizmann excelled at science and went on to study in Germany and Switzerland before taking up a teaching post at the University of Geneva. It was during this time that he started to make his mark within Zionist circles.

The first Zionist conference was held in Switzerland in 1897. Travel problems stopped Weizmann from attending but he became a regular at every subsequent Zionist congress.

‘Rock of Gilbraltar’

In 1904 he made his move to England, taking up a teaching post at the University of Manchester. While there he met the then British prime minister, Arthur Balfour, who was also the Conservative MP for Manchester.

Balfour was in favour of the creation of a Jewish state but felt that its establishment in Uganda would receive more political support. Weizmann has been credited with persuading Balfour to switch his gaze to Palestine. It was the beginning of a relationship that would have huge ramifications for the goals of the Zionists.

Upon the outbreak of World War I, Weizmann, who was now a British subject, accepted a government appointment supervising the production of acetone, which was vital for the production of mortar shells.

With this new role, his political influence grew and, working without the official authorisation of the Zionist agency, Weizmann was able to sell the Zionist dream to leading British politicians.

Weizmann’s diplomatic labours bore fruit firstly, and perhaps most significantly, with the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which promised British support for the establishment of a Jewish national home in Palestine.

This was further cemented when, in 1918, Weizmann led the Zionist Commission, which visited Palestine and worked to establish a basis for cooperation with the British military administation there.

In 1919, he led the Zionist delegation to the Paris Peace Conference which signalled the end of World War I, helping to secure confirmation of the British mandate.

Comfortable within British political circles, Weizmann always worked to balance Zionist aims with British interests in the region. He referred to this alliance between Zionism and Britain as the “Rock of Gilbraltar” of his approach.

Zionism from below

But as much as his diplomatic skills propelled him to prominance within Zionist circles and were critical in fulfilling Zionist aims, Weizmann believed that the creation of a Jewish state could not be achieved solely through political moves from ‘above’.

|

| Chaim Weizmann (left, wearing an Arab outfit as a sign of friendship) with Faisal I |

He argued that any political gains could not be maintained if there was not a simultaneous movement from ‘below’ through active and practical settlement of the land.

In a 1907 speech he made this position clear:

“The governments of the world will pay attention to us only as they will become convinced that we are capable of conquering Palestine through persistent practical work.

“Political Zionism means to make the Jewish question an international one. It means going to the nations and saying: ‘We need your help to achieve our aim; but we ourselves are doing all in our power to strengthen our position in the land, because we regard Palestine as our homeland.’ We must explain Zionism to the governments in such a manner that they shall understand it as the Jews understand it.”

Figurehead

In 1920, he was elected president of the Zionist Organisation. Although challenged by some who questioned how closely he had tied Zionist interests to those of the British, he was for much of the next 20 years the figurehead of Zionism.

But as British policy began to change – culminating in White Paper of 1939, which severly restricted Jewish immigration to Palestine, and with the revelation of the extent of the Holocaust, Weizmann was increasingly sidelined by more aggressive Zionist leaders. In 1946, Weizmann received a vote of no confidence at the post-war Zionist Congress.

However, in February 1949 – a month after Israel’s first elections – an ailing Chaim Weizmann was elected as the first president of Israel.

It was a largely ceremonial post and Weizmann found himself and his ideals frustrated within a government led by David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister. A Time article after Weizmann’s death in 1952 reported a conversation Israel’s first president had with an aide.

A year before his death, in a rare public appearance, Weizmann dropped his handkerchief. When an aide picked it up, Weizmann said: “Thank you, thank you very much, thank you very much indeed.” When the aide reflected that it was only a handkerchief, Weizmann replied: “My handkerchief is terribly important to me. It’s the only thing in the country I can stick my nose into. Into everything else, it’s Ben-Gurion’s nose.”

The man Arthur Balfour described as being able to “charm a bird off a tree” was buried in the grounds of his estate in Rehovot, near the campus of the Institute of Science that bears his name.