An unsolved murder amid Costa Rica’s Indigenous land disputes

Questions of heritage and who the land belongs to remain difficult to answer.

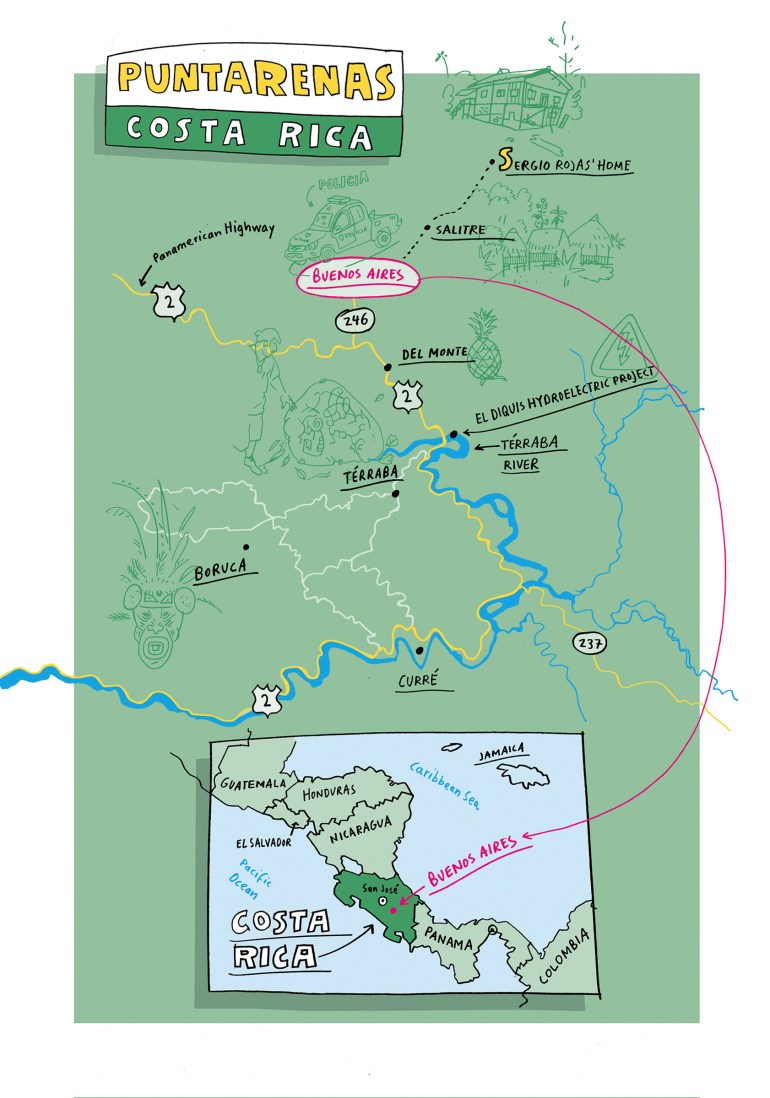

It was about three hours after sunset on March 18, 2019, when a resident of Yeri, a remote Indigenous settlement near the Pacific Coast of Costa Rica, heard the sound of gunfire from his neighbour’s home. When two policemen arrived at the crime scene a couple of hours later, they found a 59-year-old man lying in his bedroom with seven 9mm bullet wounds across his back.

News spread quickly of the murder of Sergio Rojas, the most prominent Indigenous leader in the country’s recent history.

Carlos Alvarado, the president of Costa Rica at the time, described Rojas’s death as “tragic”, not only for Indigenous peoples but also for the whole country.

Rojas, the leader of the Bribri tribe, had fought to reclaim Indigenous ancestral land, the vast majority of which had been illegally occupied since at least the 1960s.

Land is vital to the histories and identities of Indigenous people around the world, including those in Costa Rica. Their relationship to a given territory is often familial and spiritual, not to mention critical to sustaining their agricultural livelihoods and lifestyle close to nature. Rojas fought not only for land as an economic resource, but for what he believed to be the cultural integrity and dignity of his people.

But he had been a controversial figure.

In 2010, he launched a campaign to reclaim land, resulting in the seizure of 600 hectares (1,500 acres) of farms and homes owned by people his followers did not recognise as Indigenous.

At the time of his death, he was being investigated by the local Public Prosecutor’s Office for allegedly misappropriating nearly $800,000 worth of funds as president of the local governing body.

Contentious history

Rojas’s legacy is undergirded by a long and complex history of contention over land in Costa Rica.

Legal recognition of Costa Rica’s 24 Indigenous territories has been a prolonged and convoluted process since the 1930s. A lack of constitutional assurances for property and cultural rights spurred decades of tension, which led to the gunfire that took Rojas’s life.

At the heart of the violence has been a 1977 law that sowed confusion about who could own property in Indigenous areas. The nation’s eight tribes, who make up 2 percent of Costa Rica’s population of five million, live mostly in self-governed, remote corners of the country where poverty is high, access to social services is minimal, and disputes over territory are left unmitigated by government or police forces.

The law gave the Bribri and another tribe, the Teribe, legal rights to 11,700 hectares (29,000 acres) of land without allocating funds to compensate displaced non-Indigenous residents, despite a vague stipulation that they would receive payment.

The failure of the government to compensate landowners or control the illegal sale of land to outsiders has resulted in the displacement of people on both sides of the disputes.

Meanwhile, debate about who is considered Indigenous is nearly as contentious as the struggle for land tenure itself. Tribes have varying unique qualifiers for certification, a process fraught with disputes - the Bribri, for example, insist on express proof of a Bribri mother, while the Teribe accept Teribe lineage on either the maternal or paternal side within six generations.

Unsolved murder

Rojas, who became a lightning rod in this conflict, suffered a previous attempt on his life in 2012 when someone fired at his car.

In response, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights – a regional body with moral authority but little teeth – in 2015 ordered the Costa Rican government to adopt precautionary measures to protect the Bribri and other Indigenous people and investigate any danger they faced. Critics have said that no effective safeguards were put in place, particularly in the case of Rojas.

His murder remains unresolved, increasingly mired in controversy. In September 2020, investigators supervised by the Attorney General’s Office announced the dismissal of the case, arguing an absence of sufficient evidence after 18 months of secretive work.

No official suspects were produced by the investigation, although the culprit is widely considered by Indigenous activists to be either a political adversary of Rojas or a person displaced by land invasions.

Following a public outcry, the tiny court in Buenos Aires, the small capital of the Puntarenas region where Rojas lived and died, declared it would resume the probe. In January 2021, a human rights commission within the Legislative Assembly in the Costa Rican capital San José urged the central government to reopen the case. Nothing tangible has transpired since.

Who decides who is Indigenous?

Today, Rojas’s followers argue that government inaction leaves them no option but to forcefully invade property inhabited by those they deem non-Indigenous. “I will stop at nothing to continue Rojas’s legacy,” says Felipe Figueroa, who took over to lead the land reclamation movement after his death.

“We’re ready with weapons if necessary,” explains Jeffrey Villanueva, an Indigenous leader inspired by Rojas.

On the opposite side, those who have lost their land feel abandoned by the government. “My fight is against the government for not compensating me as promised by law,” says William Vega. Fifteen men with machetes who considered him non-Indigenous seized his property 10 years ago.

At the court in Buenos Aires, hundreds of cases mount from all sides of the conflict related to land reclamation, including attempted homicide, land misappropriation, and assault with a weapon.

Jean Carlo Cespedes, one of two judges in the region who preside over Indigenous land rights cases, said the central question in the continuing feuds is who has the right to define who is Indigenous.

Multiple organisations in each territory claim to certify identity, which means “everyone has an interpretation of the law designed to help their side,” according to Cespedes. No one centralised body has the power to resolve most disputes.

Without solutions from national leaders, the fight continues, the most visible conflict playing out between Indigenous and non-Indigenous neighbours. Yet Indigenous people are not necessarily united in their pursuit of justice – some continue Rojas’s legacy while others disagree with it. Others who consider themselves to be Indigenous are not recognised as such.

In remote communities far from San José and the court, tension simmers between neighbours.