‘Not a quitter’: The Karachi doctor taking rapists to court

In an old surgical wing, Dr Summaiya Syed faces great odds to bring justice to rape victims.

Warning: This article includes details about sexual abuse that some readers may find disturbing.

Listen to this story:

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsTen years after Chibok girls kidnapping: One woman’s struggle to move on

Poland lawmakers take steps towards liberalising abortion laws

Arizona’s top court allows near-total 1864 abortion ban to go into effect

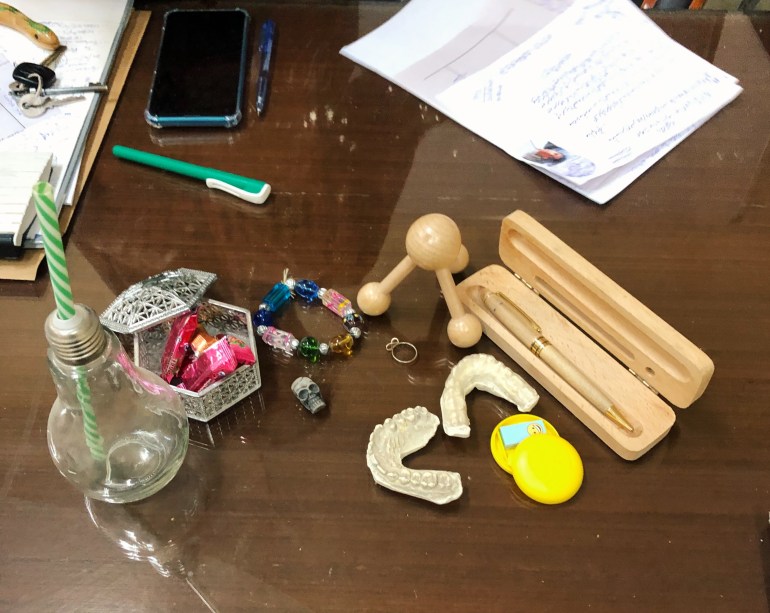

The toys on the desk are “ice-breakers” for the children, the doctor tells me. A beaded bracelet, a small toy skull, chalky white dental moulds, a glass shaped like a lightbulb with a green candy-striped straw.

When her son and daughter were younger and would eat McDonalds’ Happy Meals, Dr Summaiya Syed would save the toys from them and bring them to work to add to the stash.

She would buy dolls and hand them to a child sitting across from her in the hospital room and play a game. The doll has been hurt. “Can you show me where it is hurting?” she would ask. “Did someone touch the doll?”

If the child showed her where it hurt, where the doll had felt an unwanted grasp, Dr Summaiya would ask, “Who did this to the doll?” There are no dolls here today. The children keep them when they leave the hospital.

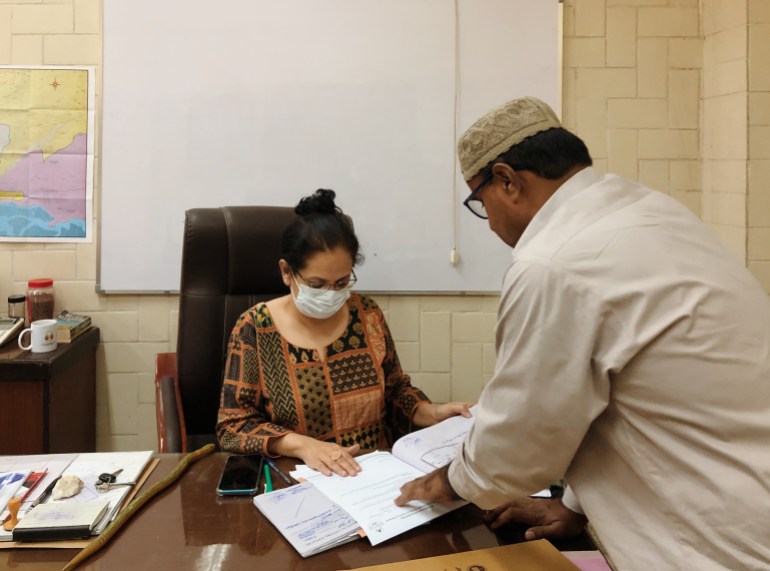

Dr Summaiya has been a woman medico-legal officer (WMLO) for 23 years. The bespectacled 50-year-old doctor looks like a kindly but firm teacher. She has a warm smile and she patiently answers questions, but when a visitor asks her to tweak the rules just a little for some paperwork he needs, she adamantly refuses.

On the day we meet, her hair is pulled back in a bun and she is wearing a casual orange and black kameez with black jeans and sandals. Dupattas only get in the way, she says.

The door to her office does not remain closed for long, with staff popping in to run a decision by her or give updates on a case. Some of them call her ‘Sir’. She answers their queries and picks up the thread of our conversation without pause.

If I’m waiting for a lull to begin asking my questions, I’ll be here a while.

“We don’t stop for anyone,” she says.

‘The bowels of society’

In 1999, Dr Summaiya, fresh out of medical school, was posted at the police surgeon’s office at Karachi’s Civil Hospital, where it was her job to examine female victims of violence including rapes, assaults and unnatural deaths, such as suicides, homicides or accidents.

At that time, she says, they didn’t even use the words “domestic violence”; it was just called “physical assault”.

“I had no idea what I was in for,” she recalls.

In medical school, while her peers were interested in lucrative specialisations, she told a friend she would like to be a coroner. And so it felt like a stroke of luck to her that she was a 27-year-old with a stable government job at a public hospital that paid 6,000 Pakistani rupees ($34) a month, tasked with determining the circumstances under which someone had lost their life or been injured.

Not everyone thought that. This is a job where you get your hands dirty.

“The MLO sits in the bowels of society,” Dr Summaiya explains. “I’ve seen bodies with heroin capsules in their abdomen, I’ve dealt with new-born children thrown on rubbish dumps, battered women, we go to graveyards for exhumations, you have to deal with the police and go to court to present your findings…” She trails off.

Most of the doctors who had been inducted with her, especially the women, requested transfers. In a city of roughly 10 million people at the time, there were only four WMLOs and, as far as she can remember, 20 male MLOs.

In the first month of her new job, Dr Summaiya dealt with the case of a girl who had been raped by her sports teacher. She was summoned to court – her first time there – to present her evidence.

Even after all this time, she still remembers the judge’s name and the court room number. “Jaffrey sahib in court room number one.”

When she was grilled in cross-examination about why the girl’s hymen seemed to have escaped injury, she quoted from the MLO’s “holy book”, Parikh’s Simplified Textbook of Medical Jurisprudence and Toxicology to explain why she could not conclusively say that it had, as she was unable to see the hymen clearly to check for injuries. “I knew that with children under the age of 10, the hymen cannot be easily visualised, and I knew exactly which page it said so in the textbook,” she says.

The judge turned to her and said, “You’re in the right field.” The perpetrator was sentenced to 14 years. It was Dr Summaiya’s first conviction. She hasn’t looked back since. “I thrive on this work,” she says.

Each case is a puzzle

An MLO is responsible for conducting a complete physical examination of a victim, collecting evidence for testing, providing treatment (such as emergency contraception in the case of rape), referring the case to the police and testifying in court if necessary. An MLO can deal with victims of incidents such as bombings, firearm injuries, physical assault, homicide, suicide, rape and sexual assault. The MLO writes a report based on their examination and records statements from living victims. Both are submitted to the police.

“I tried my hand at paediatrics, but I was too emotional with my patients to be of any use to them,” says Dr Summaiya. Even now, she is greatly troubled when she has to examine the bodies of children or pregnant women who have suffered violence.

“I can imagine the agony they were in in their last moments,” she says. “It’s a curse. I had to learn to compartmentalise and not lose my objectivity.”

Dr Summaiya is motivated by the prospect of an investigation. “I cannot sit still until a case is solved.”

Each case, she says, is like a puzzle, one that requires not just a close study of the textbooks, but good instincts. In one case, for instance, a girl was brought in by her father as he said she had been raped by their neighbour. “I felt suspicious about why the mother was not with the child at this traumatic time,” Dr Summaiya explains. She asked for the father’s blood sample.

The cells from the girl’s vaginal swabs matched with the father’s blood sample. He had lied about the neighbour to cover up for sexually assaulting his child. “These puzzles don’t bring me down, they wake me up,” she says.

When I ask where she developed a taste for mystery, she laughs. “Who knows! Agatha Christie books? A hefty dose of Famous Five? Maybe Nancy Drew or jasoosi (spy) novels.”

‘Not a regular mom’

There is no satisfaction, however, in some cases. In May 2020, when a plane crashed in a residential neighbourhood in Karachi, killing 97 passengers, Dr Summaiya did 34 autopsies in one day.

And in this city, where everyone has a story about a mugging gone awry or can tell you exactly where they were when a riot broke out, it didn’t take long for a familiar face to arrive on a gurney in her examination room. In one case, the body of a 16-year-old girl who had been stabbed by a home intruder was brought in. She was a friend’s daughter. “I lost count of the wounds,” Dr Summaiya recalls quietly.

Three years into her first job, Dr Summaiya’s son was born. When he was not even a year old, she would bring him in to work with her when she was on night duty. “You’re on call 12 hours a day, with no days off for Eid, no sick leave, no days off for a death in the family,” she says.

Her son was learning to walk, still wobbly on his legs, as she would sit at her desk and write her notes from examinations. The violence she witnessed indelibly seeped into her experience as a mother. By the time her daughter was born in 2004, she says, “I was a traumatised mom, not a regular mom.”

While her children, now 18 and 20, joke that they’re ‘prisoners’ because of her rules (curfews, no riding motorbikes, all friends must be introduced to her), she explains, “Here’s what I knew even before they were born: at even six months, a child can be raped. At 10, they can be kidnapped.”

When her son went to a concert on Valentine’s Day this year, she called him close to his 10pm curfew. He didn’t answer the phone. The concert was in a basement venue and he had no cell reception there. “For an hour, I was going crazy with worry,” she says. “I stopped short of calling the police in that neighbourhood’s jurisdiction to raid the venue.”

Changing the system

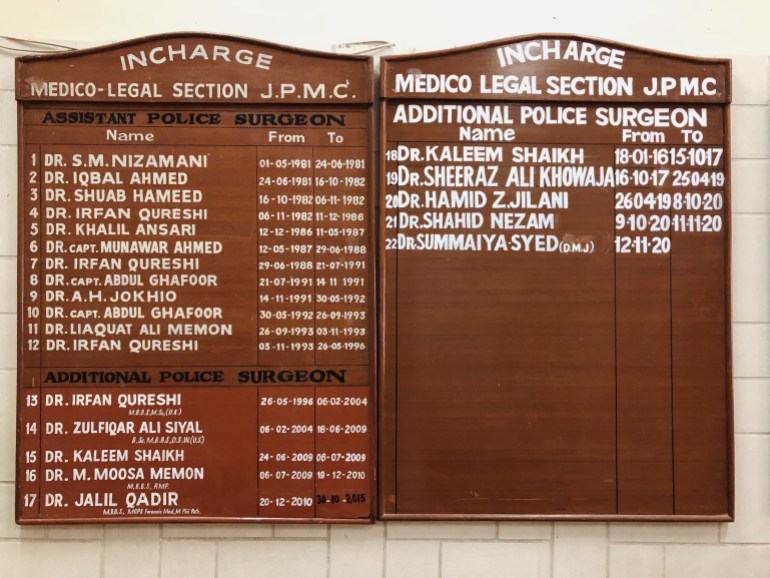

In November 2020, she started a new role, becoming the first woman to hold the post of Additional Police Surgeon, Karachi, at Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre (JPMC), one of the city’s busiest public hospitals. “I was posted here by some people who thought I could bring about a change in the system,” she explains. “My colleagues and I wanted to make this hospital the face of medico-legal standards in the country.”

Among the reforms on her agenda: the need for greater discussion on ‘object rape’, introducing standard operating procedures for the collection of samples for evidence, and no MLO working under her would be allowed to use the ‘two-finger test’ on rape victims.

Dr Summaiya describes the latter, whereby a doctor inserts two fingers into the vagina to detect if the hymen is present and how “habituated” a woman is to intercourse, as “akin to raping a survivor again”. Many MLOs, she says, persist in using the test rather than note bruising or injuries or speaking with the survivor to determine what has happened as they feel it is “quicker and easier”, and often don’t bother to take vaginal swabs or other samples once they’ve conducted the test.

In 2021, the Lahore High Court banned the test in Punjab province, saying it was “illegal and against the Constitution of Pakistan”; Dr Summaiya and a senior doctor, Dr Farhat Hussain Mirza, were tasked by the health department with supporting a petition calling for the test’s abolition in Sindh province, and the court ruled in their favour in September 2021.

“We have been working in the dark ages for so long, and that is why our judicial system is the way that it is,” Dr Summaiya says. She draws a triangle for me on a piece of paper. She writes at each point: MLO, prosecution, investigating officer. In the centre of the triangle, “judge”.

Each point needs to work together on a case for a successful conviction, she explains. In the case of sexual assault, a cursory look at the numbers tells you that this is not happening: more than 14,000 women have reportedly been raped in Pakistan in the last four years, and fewer than three percent of rapists in those cases were convicted.

Evidence for a watertight case

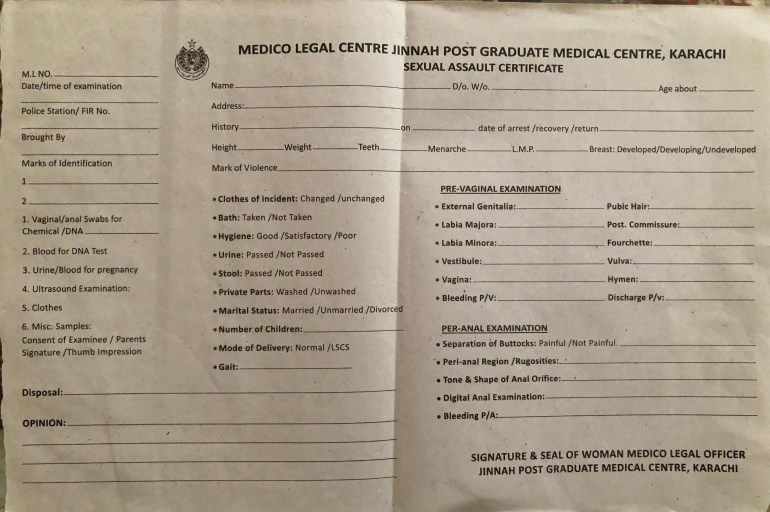

In her corner of the triangle, one of the changes that Dr Summaiya has been working on since 2016 is an overhaul of the way that evidence of sexual assault is documented.

She hands me a form with a few sections to be filled in. When she first started working, this is the kind of form she would be required to use to gather evidence. With experience, an MLO would learn that this form contains a fraction of the information needed for a watertight case. “A doctor would fill this form based on their expertise,” she explains. “A great deal was left to chance as a doctor with a day’s experience will record evidence very differently to a doctor who has 20 years of experience.”

That piece of paper is a crucial record. In 2002, in one of the most well-known cases of rape in Pakistan, 14 men in the village of Meerwala in Muzaffargarh district, Punjab, were accused of raping a woman named Mukhtara Mai as revenge for her 13-year-old brother’s alleged relationship with a woman from another tribe. She was then paraded naked through the village. Only six of the 14 men were convicted and sentenced to death. They appealed and five were acquitted. In 2005, the Supreme Court upheld this judgement by the Lahore High Court, citing a lack of evidence.

Dr Summaiya does not want anything to slip through the cracks. She places a second form on the table. It is far more detailed, with three sections documenting a physical examination, the doctor’s notes and opinion. “Look at this one,” she instructs. “Even if it was your first day on the job, the form guides you. With this, we do not have to rely on a doctor’s experience to check for certain things.”

For instance: Has the victim bathed, therefore getting rid of potential evidence? Does the victim have children and if so, what was the mode of delivery? “A woman who has had four children will present differently compared with a 14-year-old,” Dr Summaiya explains. “If she has fewer injuries, that does not mean she wasn’t subjected to rape.”

The new form asks the doctors to mention the victim’s gait. If a woman has been gang-raped, her gait is affected. A doctor must note down the dates of the incident, the victim’s recovery and the date and time they were examined. With the passing of each day, an MLO’s findings will change as evidence – traces of semen, blood, or marks of violence – can be lost.

“With all the additional information, I’m giving the police and prosecution evidence to build a case, to corroborate what the victim tells them,” Dr Summaiya says. The new form has two times the space to note down “marks of violence”, so a doctor can be as thorough as possible.

Resistance in her stride

A kitten mewls from under her chair. Dr Summaiya has forgotten to feed the litter of strays outside her office. “Come on, baby,” she says, getting up. Another kitten darts out from a corner. “The cats we take care of do have names but this is a new bunch, so for now their names are billi (cat) number 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5.”

When she returns, one of her clerks brings in a plate and she beams. Masala-covered French fries. He thought she might be getting hungry. She continues to explain the details on the new forms to me while nibbling on the fries. But then another member of her staff walks in and scolds her. “Your blood pressure is going to be high if you eat those.”

She ignores him and continues. “When I first started working, we did not have to record the victim’s consent to be examined,” she says. “If you forcefully examined someone who has been raped, what is the difference between you and the rapist?”

The forms were submitted for approval to the prosecutor general and they have been in use at JPMC for a year. Dr Summaiya describes them as an evolving document and she hopes that they will eventually be used across Sindh. She asks her MLOs – four women and three men – for feedback and plans to tweak them further, with the addition of sections such as pictograms to thoroughly document marks of violence on the body.

But the change has not come easily.

To the left of her desk is a small whiteboard mounted on the wall with the following instructions: “Stop expecting honesty from people who lie to themselves. Save your explanations for those who understand you. Give your silence to those who are determined to misunderstand you.”

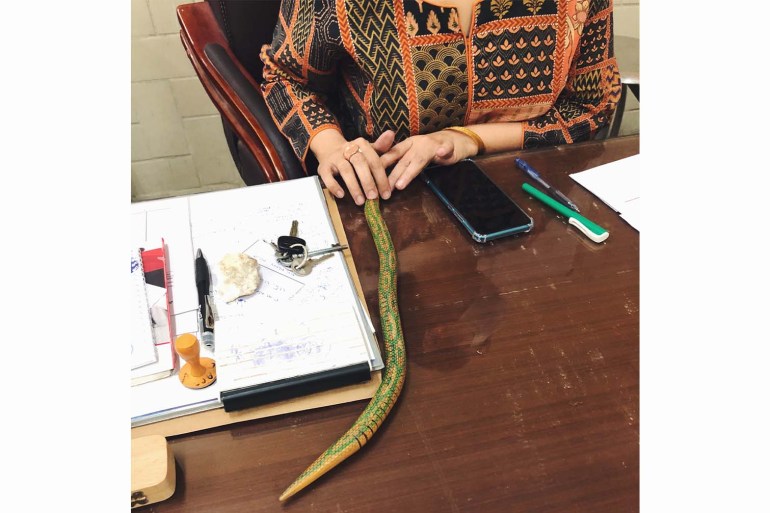

Dr Summaiya has glanced at this whiteboard often in the past year. She keeps a yellow and green rubber snake on her desk, to remind her of her enemies, she says, only half-joking.

There has been resistance to the new forms. While some MLOs said it was not their job to gather extra data and it took too much extra time, others knew that it hampered their chances of fudging data, misreporting it or leaving out information in exchange for a bribe from the perpetrators.

The form reveals poor treatment: for instance, an MLO is now required to note the time a victim was brought in and the time they were examined. “If there is a gap of several hours, the MLO gets caught, you see, and they’re not happy about it,” Dr Summaiya says. The amounts slipped under the table can significantly supplement a meagre government salary. In one case, Dr Summaiya says she was offered – and refused – 2.5 million Pakistani rupees ($14,000) to record a homicide as an accident.

She has learned to take the resistance in her stride. The hurdles are not new.

‘Stepchildren of the medical system’

The office allotted to her is located in the hospital’s old surgical wing. Faded signs for the thyroid clinic and exam rooms remain on the doors. Files are laden on stretchers and three clerks have devised a system to keep them organised. Outside the office doors, men ride their motorbikes through the corridor and paan stains walls plastered with notices to respect the hospital space and keep it clean. The office we sit in has no air conditioner, no large windows for ventilation. It would be brutal in the summer heatwaves.

Dr Summaiya has been in this room for six months, as her last office, just across the corridor, became unusable when part of the ceiling crumbled and caved in. It is now filled with sacks of old files destroyed by water damage or termites. Some of those bags may contain reports needed in court, as cases can take six months to four years to go to trial. The last time Dr Summaiya was in court this year, it was for a case she documented in 2016.

Every day, people arrive here on one of the worst days of their life and they are at the mercy of a system that seems designed to fail. There is no budget for the forms that document the violence they have endured – every month, the MLOs contribute Rs1,000 ($5.60) each to pay for the printing of forms, and Dr Summaiya makes up the deficit.

This year, the Legal Aid Society, a not-for-profit organisation offering assistance and representation, offered the funds. The victims will be examined in a room with blinds that Dr Summaiya paid for to ensure their privacy, with bilingual posters she had printed to inform them of their rights. A victim relies on the MLO to collect as much evidence as possible, but what they may not know is that the MLO may be required to buy swabs, jars, or sterile casings for samples out of their own pocket if supplies fall short. “If you don’t take on the cost, you’re weakening the case,” Dr Summaiya explains. “In court, it’s not good enough to say that you didn’t do your job properly because you didn’t have what you needed.”

Ambulance drivers share clean sheets from their supplies to cover bodies, E.R. staff provide sanitiser, PPE or gloves. Once samples are collected, a police officer will transport them to the lab, often travelling on a motorbike. In one instance, an officer carrying glass vials of samples in plastic bags got into an accident. All evidence was destroyed. “We are the stepchildren of the medical system,” Dr Summaiya says with a smile. “No one is willing to accept us or provide for us.”

There is little interest, she says, in how crucial their work is. Most doctors dismiss the MLOs as a corrupt bunch. “Our reputation precedes us, and the few who aren’t dishonest are tarred with the same brush,” Dr Summaiya explains. “After all, you don’t eat the entire deg (pot) to judge the biryani, do you? You base your opinion on one bite.”

When I ask her if she ever thinks of quitting, she laughs. “Every day! Every day I tell my husband, ‘That’s it, I’m done, I’m not going in tomorrow.’ And he reminds me, ‘That’s what you said yesterday.’”

She pulls the rubber snake on her desk closer and strokes its webbed pattern. “This is a fight that continues, and if I quit, I’ve lost. I’m not a quitter.”

In Pakistan, the hotlines for gender-based harassment or violence are 1043 (toll-free; Punjab Commission on the Status of Women; 1098 (toll-free), 0311-6641098 or email madadgaar@cyber.net.pk (Madadgaar); or 0800-13518 (toll-free; Sahil).

From the Afghan woman who fought patriarchy and the Soviets to the mother who taught her daughter what it means to survive and the art of care, we are telling the stories of women – contemporary, historical, in the public eye and overlooked – who are shaping other women’s lives. In 2022, starting from Women’s History Month in March, these are the stories of women who are making a difference to other women.