Hummus and chill: Doha weekends courtesy of Beirut Restaurant

Doha, Qatar – You know how they say good things come in small packages? While technically not small, Beirut Restaurant is certainly unassuming, and it is certainly good.

It is also part of Doha’s history and fabric, the source of many leisurely weekend takeaway breakfasts, drop-in dinners and deliveries devoured between meetings at work.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsRevisiting molokhia amid war and displacement in Gaza

Maqali, a simple Syrian dish that saved a displaced family’s Ramadan iftar

The Sikh kitchen that feeds Manila’s moneylenders

If you’ve lived in Doha, you know that Beirut is where the city’s best hummus is.

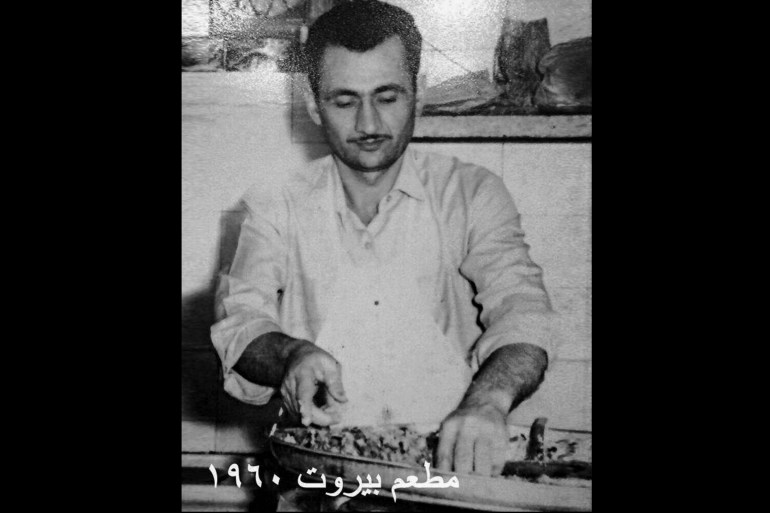

Ali Shaheen is very welcoming on the phone, confirming that, yes, he is one of the Shaheens, that his uncle founded Beirut Restaurant in 1955 and that he is an authority on all things hummus.

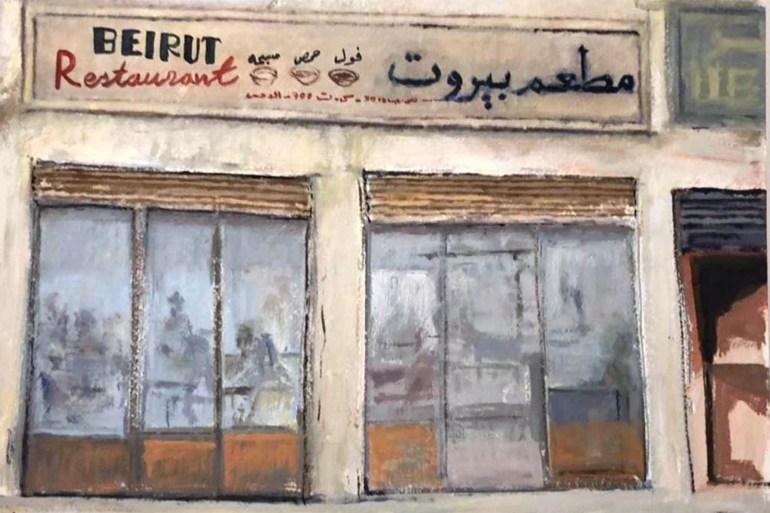

We head to Beirut’s new(er) location for a chat and a meal, winding through the streets of old Doha, shopfronts clustered along the street and parking hard to find in the bustling neighbourhood of Bin Mahmoud. Keep an eye out for a big red facade with a silver Lebanese cedar over the door.

This is not a fancy place, but its bright, clean interior makes use of those big plate glass windows, and really everyone is here to eat, eat well and go home. Ali welcomes us with a full-face smile from behind the counter, where he’s sitting with his nephew Dib.

We head over to sit at a granite-topped table with simple banquet chairs around it. At one end of the table is a box of tissues, a salt shaker and a metal shaker of cumin. These are your basic tools, but you can expect some olive oil in a no-nonsense stainless steel dispenser with your meal too.

A waiter puts simple paper placemats printed in red and green down on the table. That is the menu, in English and Arabic. There are fewer than a dozen items there because the team at Beirut knows what it does well. Ali looks at us, waiting because, of course, first we order, then we talk.

While it would have been easy enough to order everything on the menu, we defer to Ali to tell us what we should be eating. Smart move, because he turns to Dib and gives him a rapid-fire list. All we have to add is a request for mint tea and water.

Unnecessarily golden chickpeas

Dib is the third generation to be part of Beirut, which was founded by his great-uncle. The Shaheen brothers started in Lebanon, where they ran a restaurant in the 1950s, but work wasn’t going so well and they decided to leave the country in 1955. Abu Mohamed, Ali’s uncle, ended up in Qatar, and Abu Jihad, his father, ended up in Kuwait.

The brothers ran restaurants in their new hometowns for 20 years until Abu Jihad came to Doha for a visit and suggested to his brother that they sell one place and work together in the other. And so Abu Jihad moved to Doha with his family in 1975.

The food arrives before Ali finishes his story, and we suppress an urge to applaud as bowl after bowl is set on the table. Hummus, fuul, msabaha, mutabbal, falafel, tahini, teeny bowls of olives and chopped onions, and a basket of hot, fresh bread. Oh, and a no-nonsense stainless steel dispenser of olive oil.

A word before the meal begins: In Arabic, hummus refers to only two things, the chickpea itself and the puree made from chickpeas and tahini.

This hummus hugs the sides of its two bowls and surrounds generous scoops of unnecessarily golden boiled chickpeas piled in the middle and generously anointed with olive oil. Dib chuckles at our excitement as he supervises arranging the food on the table. Then we spot a third bowl of hummus, this one with a scoop of fuul (stewed fava beans) sitting in the middle.

This was the reverse of the bowl of fuul, which featured mashed, seasoned fava beans cradling a big scoop of chickpeas, the whole construction reassuringly covered in lovely olive oil. Fuul is a familiar sight, but the fuul-topped hummus is new. Ali explained that this is his favourite preparation: a base of silky hummus with a ladleful of fuul – carefully drained of any cooking liquid – straight out of the enormous stewing pots, finished with a drizzle of oil in the middle and around the outer edges.

It is sampled right away, and while silky is a word used often to describe hummus, Beirut’s version is in another league.

It is a cloud – a cloud of such savoury softness that your mouth is confused for a second: What just happened? How do chickpeas get this smooth? And what complex ingredients did it take to achieve this flavour?

The fuul beans, which sit high and dry on top of the hummus, are a great foil for all the softness. Their skins have dried a little bit, giving a nice contrasting chew, and their quieter flavour balances out the savouriness of the hummus. This dish is not on the menu, so whether you’re ordering it in the restaurant or through a delivery app, Ali says you have to specify what you want: Order a plain hummus, he says, and add (in the comments box for delivery apps) that you want a scoop of fuul from the pot and a bit of lemon on top.

Noted.

The recipe for Beirut’s hummus is a well-kept secret, and it hasn’t changed since 1975 when Abu Jihad and Abu Mohamed made it in their first Doha location, a little to the east on Kahraba Street (Electric Street), which has now been rebuilt as part of the new Msheireb Downtown. Kahraba is part of the older, more languid Doha with low-rise buildings on either side of a wide road that unfurls gently all the way to the arcades and shopfronts that sit right on it.

It is also known as the first street in Doha to have gotten electricity, no small claim to fame in a country where summer temperatures remain resolutely above 40C (104F) for weeks. Staff in the Kahraba branch appreciated the power so much, they slept in the restaurant, Ali laughs. They stayed in that location until 2010, he says a bit wistfully, and then they moved to this “new” spot.

The community on Kahraba Street was irreplaceable, Ali says. People knew each other, helped each other out, and everyone who was anyone had passed through Kahraba at some point. But with the new developments, older businesses started moving out, scattering to the four corners of a rapidly growing city.

Weekends with ‘Hummus Beirut’

Ionel, who was dining at Beirut that evening, remembers the Kahraba Street location fondly as well. The 41-year-old has lived in Doha since 2002 and recalls waking up on weekend mornings to drive nearly half an hour with his friends to “Hummus Beirut” to get their breakfast.

There, they would line up behind about 30 cars along the sidewalk in front of the restaurant. Five or six staff would be serving the cars in a constant state of motion. Some would be taking an order while others were rushing back inside to ring it up in the kitchen, passing others who were bustling out again with both hands full of carrier bags. In the time between taking an order and coming back out with it, the line of cars would have moved as the first ones got what they came for. So the waiter would look up and down the line until he found the car whose order he had.

In years of doing this, Ionel says, they never received an incorrect order. Happily loaded up with hummus, msabaha and more, the friends would then drive to the Doha Corniche, where they would sit and have their leisurely breakfast, sip on soft drinks and catch up on what was happening in their lives. Many, many large takeout containers of hummus were eaten in this manner.

So how much hummus has Ali eaten? How much hummus do the two Beirut Restaurant locations make in a day? He has no idea, but he does give us advice on how to make the dish.

He starts by mentioning that what he is describing is a small batch that his family uses to test new chickpea supplier samples. Take a 50kg (that’s 110-pound) bag of chickpeas that’s been picked over and washed, and soak them in water for 10 hours. After that, the kitchen staff pick through the chickpeas again to take out any rocks or other impurities that managed to hide in the dried chickpeas. Then they get washed again and boiled. No baking soda or any other tricks, he says, just water.

Once the chickpeas are tender, they’re drained and whizzed up with tahini, lemon and salt. Only.

Ali’s method is simple (aside from the massive amounts) and, he says, the most loyal to the pure form of hummus. How much of each ingredient you should add is up to you, he says, which is a polite way of saying that the secret recipe is not getting out.

Onion and pickled green olive

Ali is very strict about his hummus. He says he only eats it at the restaurant, never at home and not when he goes back to Lebanon for visits. He likes the simplicity of their recipe with its perfectly calibrated proportions that we will never be shared with us, the admiring public. But how does he feel about the wide range of “hummus” that’s out there?

That’s not hummus, is the emphatic reply. He recalls a time when, while on a trip to the US state of California, he met someone who was trying to set up a “hummus” brand and invited him to sample the different kinds he made. After agreeing that he could be brutally honest, Ali set about tasting. Conclusion? “No.”

For Ali and for many, many Arabs, it’s not possible to include in the hummus family these versions where the intrepid have added things like beets, roasted red peppers and the very divisive chocolate. (See the definition of hummus at the beginning of this story.) Nor would “white bean hummus” and its variations make it. Where are the chickpeas?

Had Ali tried “chocolate hummus”? It wasn’t in the kinds he listed for us. Those were beetroot, roasted red pepper and roasted garlic – the rest he either couldn’t or didn’t want to recall.

We turn our attention next to the msabaha, warm, golden whole chickpeas stirred gently into a slightly tangy prepared tahini, topped with more bare chickpeas and, of course, lashings of fruity olive oil. There’s contrast here – both a colour contrast between the tahini-enrobed msabaha and the boiled chickpeas and a textural contrast between creamy msabaha and its glistening topping.

The most popular way to eat this, the most popular way to eat everything on the table, is to scoop bites up in pieces of warm Arabic bread baked fresh on site, interspersing the bites with bits of chopped onion or pickled olives. A word though, it tastes just as good eaten with a spoon, so the bread is not a must, but you should definitely indulge in some chopped onion and pickled green olives. They provide high notes to the general creaminess.

The olives are not the juicy, oily, herby kind so well-known in the Middle East. They’re small pickled green olives, which makes their skins look a bit dry. Less picture-perfect perhaps, but the acidic pickling does a superb job of cutting through the rich chickpeas and tahini.

Family secrets

Ali believes Lebanese cooks make better Lebanese food, so all the cooks here are hired straight from Lebanon and are like family. They’ve been here for years, the newest cook having arrived 10 years ago.

The team is now working on adding more dishes to their repertoire, venturing outside the chickpea and sesame kingdom into shawarmas, pizzas and more.

One thing the staff do not make, though, is the hummus. They serve it but don’t prepare it.

Only Ali and his brothers make the silky, silky stuff that has put Beirut firmly on the Doha dining map. Nobody is allowed to stand around and help. Nobody is allowed to know how it’s made, period.

At one point, Ali will teach the kids, so they can work in the restaurant going forward.

We certainly hope he does, so future generations of Dohaites can indulge as we have.