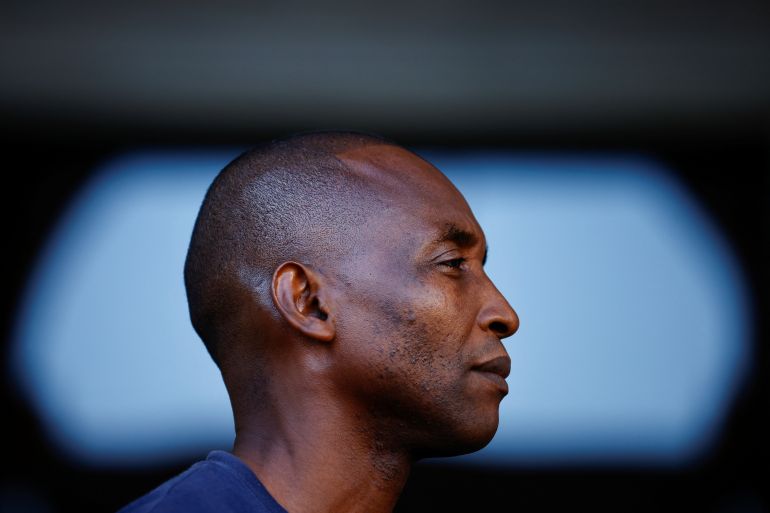

The Ivorian immigrant elected to Italy’s conservative parliament

He is the only Black lawmaker in the lower chamber of 400 deputies and one of a handful ever elected in Italy’s history.

When Aboubakar Soumahoro was a teenager in his native Ivory Coast, he used to clean shoes and dream of going to Italy, filling a scrapbook with pictures of Italian fashion designs that he cut out of magazines.

He made it to Rome in 1999, aged 19, but was shocked by the harsh reality of migrant life in a country he had idolised.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsChildren among 16 dead after asylum-seeker boat capsizes off Djibouti: UN

Five people die in attempt to cross English Channel to the UK

UK passes bill to deport asylum seekers to Rwanda: What’s next?

“Sleeping rough in the streets was traumatic, especially when I realised that this was the result of a political decision that targeted the migrants,” Soumahoro told Reuters news agency.

Now an Italian citizen, the 42-year-old has a unique opportunity to reshape such decision-making – from within parliament.

He won a seat in the lower house for the Green and Left party in the September 25 national election and hopes to make his mark from opposition ranks, facing a victorious conservative coalition that has promised to crack down on asylum seekers.

“One thing I will try to do is make sure that no one ends up living in the streets like me. People need to be treated as human beings regardless of what passport they have,” he said, speaking in advance of the October 13 opening of parliament.

He will stand out as the only Black lawmaker in the lower chamber of 400 deputies – one of only a handful ever to have been elected in the 160-year history of Italy.

Soumahoro says with a smile that he will have the “best suntan” in parliament, but is adamant that he intends to speak for the poor and disfranchised, regardless of their colour.

“I do not want to represent just one part of society. I want to make sure that everyone, both the dispossessed and those who struggle to make ends meet, can recognise themselves in what we do,” he said.

‘Us’ and not ‘I’

Soumahoro’s election is the culmination of an astonishing personal journey that included picking crops in the fields, laying bricks, working at a gas station, studying sociology at Naples University and writing a book: Humanity in Revolt.

He is reticent about his personal life, saying only that he has a young child and remains in touch with his family in West Africa. “It is more important to talk about ‘us’ and not ‘I’,” he said, adding that Italian politics was far too personalised.

Within a few years of his arrival in Italy, he became an activist helping migrants without official documents, focusing on the exploitation of farm labourers. He subsequently founded a union representing agricultural workers.

He says right-wing parties that are about to take power have politicised the migrant issue for electoral gain.

Both Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy party, which took most votes last month, and Matteo Salvini’s League party, have promised to block boat migrants from North Africa and adopted what they call an “Italians first” policy.

“Putting Italians first is not going to pull 5.6 million Italians out of poverty,” he said, accusing the right of failing to grasp the severity of problems faced by common families.

The election winners have said they will roll back a so-called citizens’ income, which provides a monthly stipend to the poor and unemployed. Soumahoro said instead of being curtailed, it needed to be expanded to help more people.

“Politicians haven’t seen the coming hurricane of poverty,” he said, warning that rising energy and food prices would create growing desperation and arguing that a more equitable distribution of wealth would ease gathering social tensions.

“The politics of happiness is real,” he added. “It can be done.”