From jellyfish to elephants, biodiversity keeps the world turning

But with a million species at risk of extinction the interlocked web of life is under threat.

![Illustration: The Green Read - June 4 [Jawahir al-Naimi/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/ade756dd4c6b4a11b105ea5a658e2311_18.jpeg?resize=770%2C513&quality=80)

In a remote part of the Pacific Ocean, amid stunning limestone cliffs and turquoise waters, you will find the extraordinary marine lakes of Palau. These are effectively islands of sea surrounded by land, connected by cracks and fissures in the rock to the ocean beyond. Slide yourself in, armed with snorkel and mask and you will behold an astonishing sight.

Millions upon millions of harmless golden jellyfish gently pulse in the warm surface waters. They have evolved to harvest energy directly from sunlight. And they are a breathtaking example of the wonder of life on Earth.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMelting glaciers, rising seas: Approaching climate tipping points

The climate crisis: Preparing for what’s already here

The US is back in the climate fight

Jellyfish generally fulfil a kind of extras’ role in the theatre of marine life as the major conservation parts go to the star players like whales, sharks and turtles.

But there is another actor in the depths, unseen and unheard, yet it plays a far bigger part than all other marine life combined. Microbes. Trillions and trillions of them.

Harmless viruses

Ninety percent of all life in the oceans, by weight, is microbial. The big stuff, those whales and other charismatic megafauna, are actually pretty trivial in terms of overall biomass.

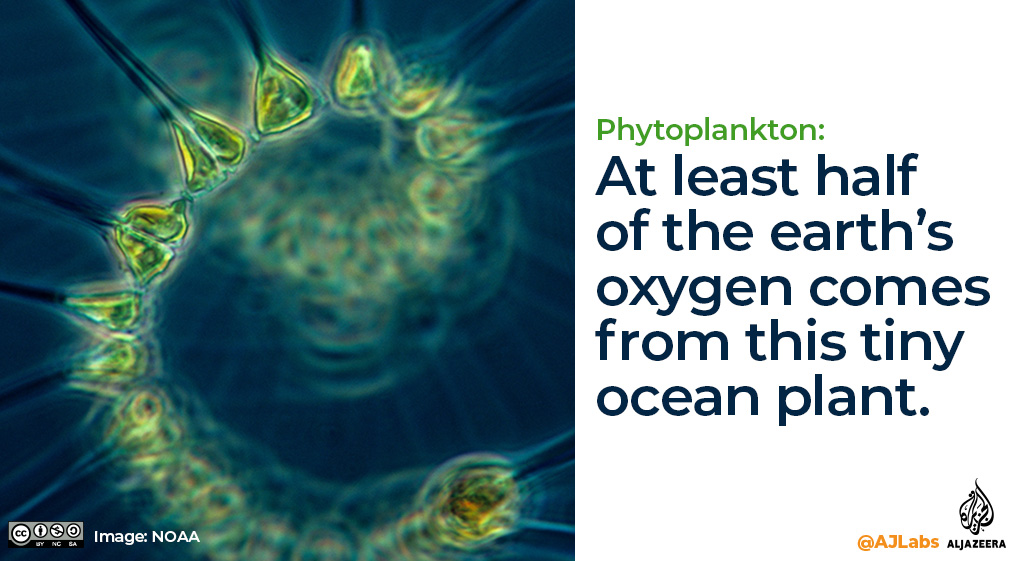

This invisible majority produces half the oxygen on the planet – every second breath that we take.

And in these coronavirus days, it is curious to note that a massive part of microbial life is comprised of viruses, almost all harmless to us. In just one litre of seawater, there are more viruses than there are people on the planet. And there are more viruses in the world’s oceans than there are stars in the universe.

I spoke to the University of British Columbia’s Professor Curtis Suttle, one of the world’s foremost experts on viruses and their role in the environment. He told me about the crucial role viruses play in the earthly ecosystem.

“Essentially we’re bathed in viruses in the water and in the air around us,” he explained. “But viruses are very specific about what they infect so most of the time they don’t hurt us. But they do kill about 20 percent of living material in the ocean every day.

“Viruses infect organisms, they then replicate and they essentially control populations. Without death, there is no life and so viruses are essential because they’re responsible for the turnover of organisms in the ocean.”

It is this interlocked web of life that makes our natural world turn. But as we mark World Environment Day we know that biodiversity on Earth is under threat. A 2019 UN report revealed more than a million species are at risk of extinction.

The UN’s environment chief Inger Andersen told me that this is critical because biodiversity is the foundation of the natural world.

“Nature is a finely tuned system where each species plays a role in the overall puzzle,” she explained. “And that’s why we’re calling for active engagement in conservation. If you will put nature under pressure it will not be as intact and it will send us a message.

“COVID-19 is one of these messages that we need to understand. We can’t continue to undermine and encroach on nature and expect nature to remain stable.”

Microbes were around long, long before humans and no doubt will be here long after us.

But for you and me, and the rest of the world’s wondrous biodiversity, it is very apparent that the world needs to act right now to save a common environmental heritage, accumulated over hundreds of millions of years.

Your environment round-up

1. Could humanity be finished?: That is what primatologist Jane Goodall fears if we fail to overhaul our food habits to prevent a future pandemic.

2. Green solidarity with the Movement for Black Lives: “There is no climate justice without a racial analysis,” Tamara Toles O’Laughlin from the US campaign group 350 said on Tuesday, as protests over the killing of George Floyd continued. Others voicing concern included the World Resources Institute, Greenpeace, ActionAid and US Climate Action Network, calling for “reckoning and change”.

3. US-UK trade: Another thing to keep an eye on is London-Washington trade talks. The US holds the trump cards, but one emerging UK red line is around food standards and the environment, with an unlikely yet powerful alliance of farmers, faith groups, centre-right newspapers and Winston Churchill’s grandson calling for a ban on US food imports. Parliament is due to debate the plans on June 9.

4. Floods, cyclones, sun and hurricanes: Devastating floods hit East Africa in mid-May, leaving hundreds dead and thousands homeless. Super-cyclone Amphan smashed Bangladesh and India in late May, leaving 14 million without power and killing more than 100. In the UK sunshine levels have spiked, according to the Met Office. “We broke the sunshine scale,” said one researcher. Hurricane season in the US and Caribbean starts on June 1, with forecasters warning that storms could be worse than normal this year. Typhoons in the Northwest Pacific typically intensify from May onwards.

5. Some hope for rainforests: In 2019, the tropics lost 11.9 million hectares of tree cover. Nearly a third were primary forests – the equivalent of losing one football pitch of primary forest every six seconds. But there were bright spots: Colombia, Ghana and the Ivory Coast had notable declines in primary forest loss. Experts Mikaela Weisse and Elizabeth Dow Goldman explain what the 2019 Global Forest Watch tree cover loss data means for the future.

The final word

You could also ask who's in charge. Lots of people think, well, we're humans; we're the most intelligent and accomplished species; we're in charge. Bacteria may have a different outlook: more bacteria live and work in one linear centimetre of your lower colon than all the humans who have ever lived. That's what's going on in your digestive tract right now. Are we in charge, or are we simply hosts for bacteria? It all depends on your outlook.