Project Force: Where could North Korea’s missiles strike?

North Korea has long wanted to develop long-range missiles that could reach the US. Now it may have achieved that.

For years, North Korea has been working steadily to build missiles with sufficient range to strike at its potential enemies, no matter how far afield. For a long time, it has been producing missiles with the range to hit its regional neighbours, but what it really wants is to develop some which can strike as far away as the United States. Now, it may have done exactly that – at least in theory.

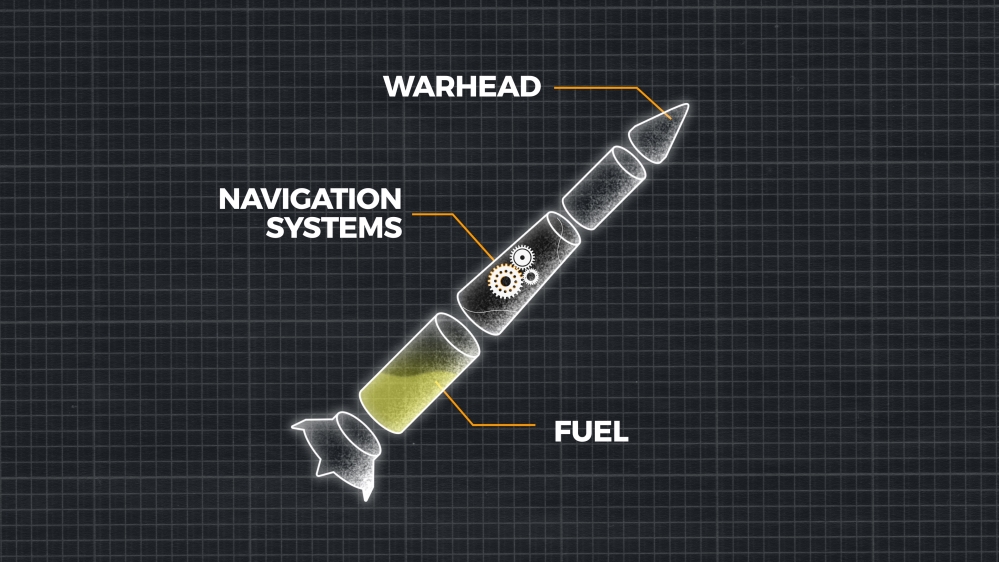

Why missiles and not, say, aircraft? Missiles have some unique advantages. The first is speed, the second is they are very hard to stop. Ballistic missiles fly in a parabolic arc towards their targets, leaving and then re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere at several times the speed of sound. This makes them very difficult to intercept. They can deliver a large warhead with reasonable accuracy very quickly and with a high chance of getting through an enemy’s defences. The longest-range missiles would take about 30 minutes to strike a target halfway around the world.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsHong Kong’s first monkey virus case – what do we know about the B virus?

Why will low birthrate in Europe trigger ‘Staggering social change’?

The Max Planck Society must end its unconditional support for Israel

North Korea has been very good at reverse-engineering old Soviet missile types, producing successful medium-range missiles like the Nodong, the technology which it exported in the mid-1990s – first to Iran, which produced the Shahab-3 medium-range missile, then to Pakistan which built its own version, the Ghauri.

The difficulties began for North Korea’s engineers and missile designers when they started working on longer-range designs. Previous illegal missile launches since 2006 had resulted in UN sanctions against North Korea, which prohibited the transfer of missile technology. Test failures started to spike as engineers found it increasingly hard to incorporate their own designs with engines and parts bought on the black market.

The Taepo-Dong-2, a missile with a theoretical range of 10,000km (6,200 miles), was sidelined after several such failures. A variant, the Unha-3, was eventually used to launch satellites, with a patchy success rate.

Despite featuring prominently in military parades in North Korea, the Musudan intermediate-range missile failed every single test launch but one, blowing up soon after takeoff.

In order to increase the range of a missile, designers often lengthen the body of an existing design, using the extra space for more fuel. This throws the balance of the missile off, making it unstable in flight. It then starts spinning out of control, tearing itself apart and rendering itself useless as a weapon.

Results were partial at best, with engineers struggling to develop a reliable long-range missile and failures were far more common than successes. Then, in 2017, all that changed.

Success

In May 2017, after three initial failures in April, the first successful test of the Hwasong-12 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) was recorded. The largest single-stage missile to be made by North Korea, it flew for 787km (489 miles) before splashing down in the Sea of Japan. While this distance was kept short not to antagonise the North’s neighbours, its potential range was estimated to be 4,500km (2,800 miles), easily in reach of the US air and naval bases on the Pacific island of Guam.

Several things became apparent to military observers. This missile had a new, powerful engine, the airframe was lighter than on previous models and it was using a more potent fuel.

All these qualities were vital if this was to be a “stepping-stone” design for an eventual intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). A successful series of launches conducted in the second half of 2017 clearly showed the North Koreans had finally overcome the previous challenges that had plagued the programme.

Kim Jong Un clearly thought so, as the design engineers were feted as heroes in the capital, Pyongyang.

Although the projected range of the Hwasong-12 fell short of the 5,500km (3,400 miles) that defines the minimum range of an ICBM, North Korea now had a proven, successful intermediate stage on which to base the design for a long-range missile.

Flushed with success, North Korea moved forward and successfully tested the Hwasong-14 on July 4, 2017, as Americans celebrated their national holiday. A two-stage missile, its projected range was at least 6,700km (4,160 miles), meaning it could target cities on the west coast of the United States, comfortably falling into the ICBM category.

If that was not alarming enough to Western observers, on November 28, 2017, North Korea went ahead and successfully tested the Hwasong-15, a true long-range ICBM, capable of reaching most if not all of US major cities with a 500kg warhead.

And that is not all. North Korea’s designers also managed to test a solid-fuelled medium-range missile that year called the Pukkuksong-2. This was important for several reasons: the solid fuel meant fewer support vehicles were needed and the launch time was now a matter of minutes rather than hours.

The missile was mounted on a tracked transporter, known as a transporter/erector/launcher or TEL. Most missile transporters are wheeled, meaning they have to stick to North Korea’s rudimentary road system, with an increased risk of detection. But this one could go off-road and easily conceal itself. The missile itself was canisterised, which meant it could survive any potential knocks and bumps when travelling over rugged terrain.

In short, the transporter could go anywhere, would be hard to find and had the ability to launch its missile very quickly.

By the end of 2017, it became clear that North Korea had made a quantum leap in its design expertise.

To remind the world why these missiles were being built, in September 2017, North Korea tested its most powerful nuclear device yet, at about 250 kilotons. For a sense of what that means, the Hiroshima and Nagasaki nuclear attacks were 16 kilotons and 21 kilotons, respectively.

Getting there, but a long way to go

With all these tests, the emphasis from commentators has mainly been on projected range and possible intended targets, to give the public an idea of what these new missiles could do. North Korea has launched its test missiles on what is called a “lofted trajectory”. This means the missile reaches maximum height rather than the maximum range, allowing designers to test engines, examine stresses on the missile body itself and generally see if the missile is stable in flight. Politically it is also wiser as already nervous neighbours do not have their airspace overflown, but this is still a long way from an operational test.

There are still significant design challenges to overcome. Is the missile reliable enough to be considered an operational weapon rather than a political tool? Can the warhead survive re-entry into the atmosphere, considering it will be moving at hypersonic speeds, and friction-generating temperatures in the thousands of degrees Centigrade? Then there is the question of accuracy. A missile might be able to travel as far as Guam but is it accurate enough to hit anything of value, even with a nuclear warhead?

Yet despite these many challenges, it is clear that North Korea has come a long way, in just a few years, to

developing a survivable, flexible, credible nuclear force. This would be a genuine deterrent to any military action against the North and a powerful bargaining chip in any future negotiations.

The key is diversity and the successful test of an underwater-launched ballistic missile, the Pukguksong-3, in October 2019, gives North Korea a larger range of options. Now it can launch nuclear weapons on long-range ICBMs, from remote areas on its solid-fuelled, mid-range missiles and also potentially from its embryonic force of ballistic missile submarines.

The country however still has a long way to go before it develops a true retaliatory “second-strike” capability. It has only tested its ICBM once, albeit successfully. Its submarines have never operationally tested a ballistic missile, opting instead to launch from an underwater barge (considered the safer option as it does not endanger a valuable submarine along with a trained crew). There is also little indication that North Korea has even mastered the production of a nuclear warhead that would be small and light enough to be carried by a missile.

Although much touted, in parades and via the world’s press, the truth is that North Korea’s missile force is tiny at approximately 46 missiles, in comparison to that of, say, the US, which has at least 659 highly operational and reliable missiles and strategic bombers. Nevertheless, despite sanctions and a partial moratorium, the country has managed to successfully develop and refine its designs and is well on its way to having a viable range of options to deliver a nuclear weapon to its target.

These options make it increasingly difficult for opposing military commanders to be certain they can stop all nuclear missile launches, weakening any guarantee that all of them could be intercepted and destroyed before at least one got through. This in turn lowers the chances of any successful military action against North Korea, helping to ensure the survival of the regime. The only choice, then, is for international negotiations with Kim Jong Un to resume, the leader now able to bargain from an increasingly strong position.

Video production and additional reporting by Adam Adada.