Pakistan’s Women’s March: Shaking patriarchy ‘to its core’

Young activists and their older counterparts explain why they are uniting to fight for women’s rights in Pakistan.

Thousands of women have marched across Pakistan’s main urban centres to mark International Women’s Day.

It is the third successive year that the Aurat March, women’s march, has been held in the country.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsTen years after Chibok girls kidnapping: One woman’s struggle to move on

Poland lawmakers take steps towards liberalising abortion laws

Polish lawmakers debate reforming strict abortion laws

The theme for this year’s march was “Mera Jism, Meri Marzi” (My body, my choice), which according to the organisers’ manifesto, is about demanding a society without exploitative patriarchal structures and control of economic resources, the right of women to make decisions about their own bodies, and ending harassment, forced religious conversions and the sexist portrayal of women in the media, among other things.

The marches were organised by a collective that includes Women’s Action Forum, a women’s rights organisation, Women’s Democratic Front, a socialist-feminist organisation, and Hum Aurtein, a feminist group.

“The women who are emerging are shattering all those [patriarchal] ideas. They are just not going to take it any more. This is very unsettling for a lot of people,” explained Ammar Rashid, president of the Punjab chapter of Awami Workers’ Party, a left-wing political party that supported the marches.

“The thought of a women’s march advocating women’s rights shakes patriarchy to the very core.”

Fatima Hassan is a student activist who attended the march in Karachi. “I’m a young woman [and] I’m here today because I don’t feel comfortable walking alone at night,” she explained. “And I’m here for all those women who couldn’t be here today.”

In recent months, Pakistan has seen a wave of protests – by women demanding equality, students demanding the reinstatement of student unions and ethnic groups demanding their rights.

Tooba Syed is the political representative of the Women’s Democratic Front and one of the organisers of the Islamabad march. She feels that all of the recent protest movements have one thing in common: they are being led by the country’s progressive youth.

And among the youth, women are becoming particularly vocal, she says.

“The space for women is growing. I see many more women engaging today than I did perhaps five years ago. I remember being the only woman at some protests and sometimes I would be joined by maybe two or three more women but today that has changed.”

The backlash

But if more women are feeling empowered to come out and march, it has not come without a backlash.

Some of the signs carried at last year’s marches attracted a lot of animosity. Among them were posters addressing unwanted sexual advances, explicit photos women receive from men online and even the “correct way” for a woman to sit.

Aurat March, Slogans and Posters https://t.co/5cz5m4zlqS pic.twitter.com/iL4cLDcrq9

— Bina Shah (@BinaShah) March 9, 2019

As this year’s march approached, those who opposed it became more vocal.

Maulana Fazl ur Rehman, the leader of the religious right-wing political party Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI-F), asked law enforcement bodies to take action to stop the marches.

“If they want to bring awareness to the issues that are faced today in society, if they are associated with rights for women granted to them in Islam and the constitution we have absolutely no problem with that. What occurred last year was against the norms of culture and society. So much so that I cannot even bring myself to speak of them,” he told Al Jazeera in a telephone interview.

At least three petitions were filed in courts across the country with the aim of stopping the marches. A petition in Islamabad was filed by JUI-F and Umme Hassan, wife of the Muslim leader from Islamabad’s Lal Masjid.

None of the petitions was successful.

Lawyer Azhar Siddique, one of the petitioners whose case was dismissed by the Lahore High Court, argues that the entire movement is part of a Western agenda to ruin the culture of Pakistan. “I have worked for women’s rights more than these people [the marchers]. And where in Pakistan other than a few places has there been discrimination against women?” he told Al Jazeera.

Nighat Dad, a lawyer and one of the organisers of the march in Lahore, disagreed.

“Is it not true that children are raped and killed every other day? Is it not true that girls are deprived of education? Is it not true that women who have to walk to their workplaces are harassed on the streets?

Is it not true that women face the double burden of making money as well as taking care of children and the entire household? If all of this is true, then why create such a stupid drama about one or two posters?” she asked.

“They don’t want to hear or see women taking to the streets against economic injustice and patriarchal violence that are both tied in together,” Dad added.

According to the Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (2012-13), almost 32 percent of women have experienced physical violence in Pakistan and 40 percent of ever-married women have suffered spousal abuse at some point in their life.

These numbers are likely to be an underestimate as, according to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), one in two Pakistani women who have experienced violence never sought help or told anyone about it.

According to Human Right Watch, 32 percent of primary school age girls are out of school in Pakistan, compared with 21 percent of boys. By ninth grade, only 13 percent of girls are still in school.

Silencing

There are other types of opposition the organisers must navigate.

On March 3, in Islamabad, a mural of artwork made by people involved with the women’s march was destroyed by students from a nearby religious school within hours of it going up.

On February 23, in Lahore, posters made by march volunteers and participants were torn down.

Recently, an exchange between Khalil ur Rehman Qamar, a well-known television serial writer, and writer Marvi Sirmed, that was aired live on a debate-style show on Neo News went viral. In it, Qamar shouted abuse at Sirmed over the My Body, My Choice slogan.

Neo News CEO Nasrullah Malik subsequently apologised to Sirmend on social media.

@marvisirmed Please accept my sincere apology on the incident which happened today on our screen. Being Head of NEO NEWS I am extremely sorry for that and strict action will be taken. We condemn the behaviour of Khalil Qamar.

Nasrullah Malik

Executive Director

NEO NEWS— Nasrullah Malik (@NasrullahMalik1) March 3, 2020

“Men like Khalilul Rehman Qamar want to deflect attention from the fact that the global economic crisis is begetting social movements pioneered by women and that is why they make so much noise about a select few placards,” said Dad.

“The foundations of patriarchy stand challenged today and since these foundations are so fragile, their guardians have jumped into action and are resorting to every measure in their capacities to ensure that women are back to being silenced.”

Al Jazeera attempted to reach Qamar for a comment but was unable to.

Religious parties

In advance of Sunday’s marches, a smaller rally of approximately 300 people was held on Saturday night in Sukkur, in the southern province of Sindh.

Arfana Mallah has been an activist in Pakistan’s Sindh province for more than 20 years. She is from Women’s Action Forum, a leading women’s rights organisation, and one of the co-founders of the Sukkur rally.

She chose Sukkur because, according to data compiled by Women’s Action Forum, in the last year there have been at least 50 forced conversions and marriages of women from religious minorities in the city.

“The slander on social media against us is insufferable,” she said. “There are thousands of posts they are putting up constantly against us, and saying we are vulgar and immoral women and it’s acceptable to kill us for the sake of honour.”

She believes Pakistan’s powerful right-wing religious parties are particularly concerned by the women’s movement for equality because they cannot control it.

“And if women step out of [the limited role they allow them] what will they have left to define chastity on?” she said of these parties.

Pushpa Kumari is an activist from Hyderabad who works to stop forced kidnappings, conversions and marriages of Hindu girls who attended the march in Karachi. She said many of the girls affected are between the ages of 10 and 14.

“Those girls cannot be here today,” she said. “Those girls are broken down so much that there is nothing left.

“There are two girls from my family who were kidnapped; we don’t even know if they are alive,” she added.

‘They don’t know the women of Pakistan’

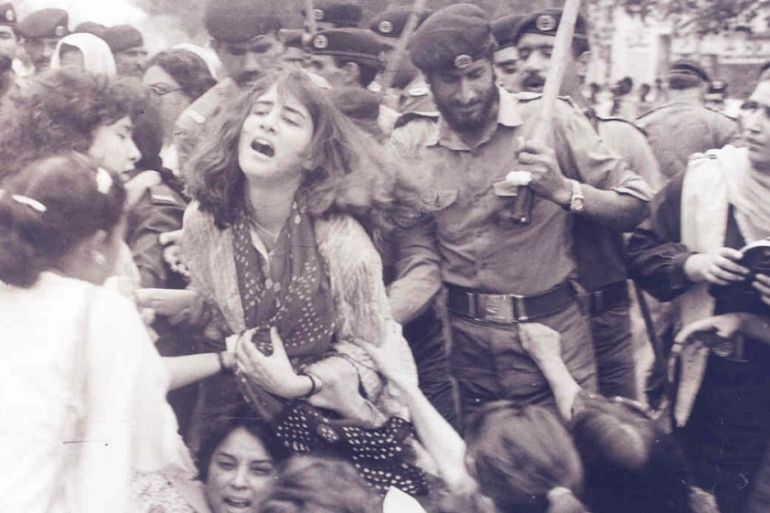

In February 1983, a group of women marched through the streets of Lahore, despite martial law which prohibited gatherings of more than two people.

They were met by police who hit them with batons and arrested them.

The protest was against the law of evidence, which would reduce the testimony of a woman to half that of a man.

Farida Shaheed was there that day in 1983, and today she helps younger women protest.

She says the marchers were called immoral back then too. The only difference then, she adds, is that people seemed particularly alarmed by women having short hair, whereas that does not seem to be such a concern now.

“There is a … so-called politics of respectability,” she explained. “What is respectable and what is not, what is permissible and what is not is a debate.

“My fundamental question is, who defines what is respectable and what is not? The problem is that these people don’t seem to know the women of Pakistan any more. They are completely mistaken about where this country and its women are.

“We have incredibly talented, innovative, powerful, active young women and they are coming together with the older and we are all united,” she said.

Nadira Hasnain was nine years old when Pakistan came into being in 1947. She sat perched on a chair near the stage at the Karachi rally.

“How society has evolved frightens me,” she explained. “In my family and growing up in a newly made Pakistan, the education of women wasn’t questioned. The safety of women wasn’t an issue.”

Ghinwa Bhutto, the wife of Murtaza Bhutto, the slain brother of former Pakistani Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, also attended the march in Karachi.

“Finally, spring is here,” she told Al Jazeera. “This movement, along with other movements, is a sign that … people are getting stronger and the rulers are getting weaker.”

“The people want discourse. There is a change in what people are willing to accept. Being gay, lesbian, gender issues, socialism, progressive politics – this is all being slowly accepted and absorbed by the people.”