Algerian women embrace a spirit of resilience and revolution

A new generation of Algerian women are finding inspiration in female freedom fighters from the country’s past.

A year ago, Algerian newspaper El Watan published a message delivered by one of the country’s best-known revolutionary figures, Djamila Bouhired: “It is up to you all to draw your future and shape your dreams. Do not let them ruin your noble fights. Do not let them steal your triumph.”

The now 84-year-old heroine of the Algerian war of independence was speaking to protesters taking part in the continuing anti-government “hirak” movement, but her words specifically targeted the youth.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsTen years after Chibok girls kidnapping: One woman’s struggle to move on

Poland lawmakers take steps towards liberalising abortion laws

Arizona’s top court allows near-total 1864 abortion ban to go into effect

Those words were echoed last month by actress Lyna Khoudri, who quoted Bouhired when she won the Cesar award for Best Female Newcomer at the Cannes Film Festival. The 27-year-old was recognised for playing the lead role in Mounia Meddour’s film, Papicha, which is set during Algeria’s civil war.

For Nahla Naili, a close relative of Bouhired’s, this demonstrates that the spirit of the country’s female revolutionaries – whom she said were the backbone of the liberation movement – lives on today.

“I am extremely proud of how [their] combat has been recognised across the younger generation,” she told Al Jazeera. “But that being said, I’d also like to put forward and recognise the battles that are being fought by other extraordinary [Algerian] women, who have stayed anonymous.”

Naili, 33, was raised in Algiers before she moved to Paris to complete a doctoral thesis in art sciences. Having grown up surrounded by prominent female figures – such as her own grandmother, Fatiha Bouhired, a rebel during the battle of Algiers and aunt of freedom fighter Djamila Bouhired – Naili has always had an undying passion for her country.

She also serves as the secretary-general of the Save the Casbah Association of Algiers. The initiative focuses on the preservation of the “Casbah” quarter, a UNESCO World Heritage Site where 1966 Academy Award-nominated film, The Battle of Algiers, was filmed. The group is hosting an exhibition over the summer to display the works of Algerian artists.

“Art contributes to the saving of the collective memory of [Algeria’s] culture,” said Naili.

“Our generation wants to rehabilitate our culture, simply because it is attracted by the truth … and film also plays a big role. For instance, when we see movies like Papicha win prestigious awards, it evokes a [feeling of] optimism, that our stories are being heard across the globe.”

‘The Black Decade’

Although the film has been banned in Algeria, Papicha encompasses a pivotal moment in history. It is set during the civil war of the 1990s that erupted nearly three decades after a revolution brought about the end of French colonialism.

The civil conflict began in 1992 after the Algerian military staged a coup d’etat to stop the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) from winning the second round of what would have been the first democratic elections. Violence became widespread when various armed rebel groups waged a war against the government. They would often issue death threats to women for reasons such as the refusal to comply with strict dress codes, or working in professional careers.

Often referred to as the “Black Decade”, the civil war era still haunts Algerians today. Some 200,000 civilians were killed – thousands of them women.

Three of them were 21-year-old Karima Belhadj, assassinated by members of an armed group in April 1993 while on her way home from work; Katia Bengana, 17, whose life was cut short after she was shot on her way to school in February 1994 – she had earlier refused to wear a hijab; and 30-year-old Nabila Djahnine – a prominent feminist – who was killed in a drive-by shooting during a protest march in 1995 in the town of Tizi Ouzou, where she had studied, earned a degree and begun her career.

But the threat of violence and oppression pushed many women of the era to fight back, Naili said.

“During the Black Decade, my mother took part in the resistance with a group of other women, because they’d been convinced to continue the legacy of our freedom fighters from the revolution.”

Saliha Heddaji, 42, recalls those years as being like a nightmare. “I was a student back then. I remember people began to threaten young girls who would go to class without wearing a hijab,” she said.

“And one day I came home, I heard screaming in the whole building. I went upstairs and found my apartment door open, and saw my mum on the floor crying. I’d been told that my oldest brother – who was my whole life – had been shot and killed at just 23 years old, while he was helping my uncle at our family’s store.”

Who had him killed is still unknown. Heddaji, the second-oldest in her family, would regularly visit the police station to check on her brother’s case, but said she was never given any information. The family believes the armed groups were responsible for his death.

“I had my final exams just three days after [he was killed],” Heddaji said. “I don’t know how I did it, but I still went and passed all my exams, because education has always been very important for me. I ended up being in the top five of my class, and that was my first year in pharmacy school.”

Striving for female literacy

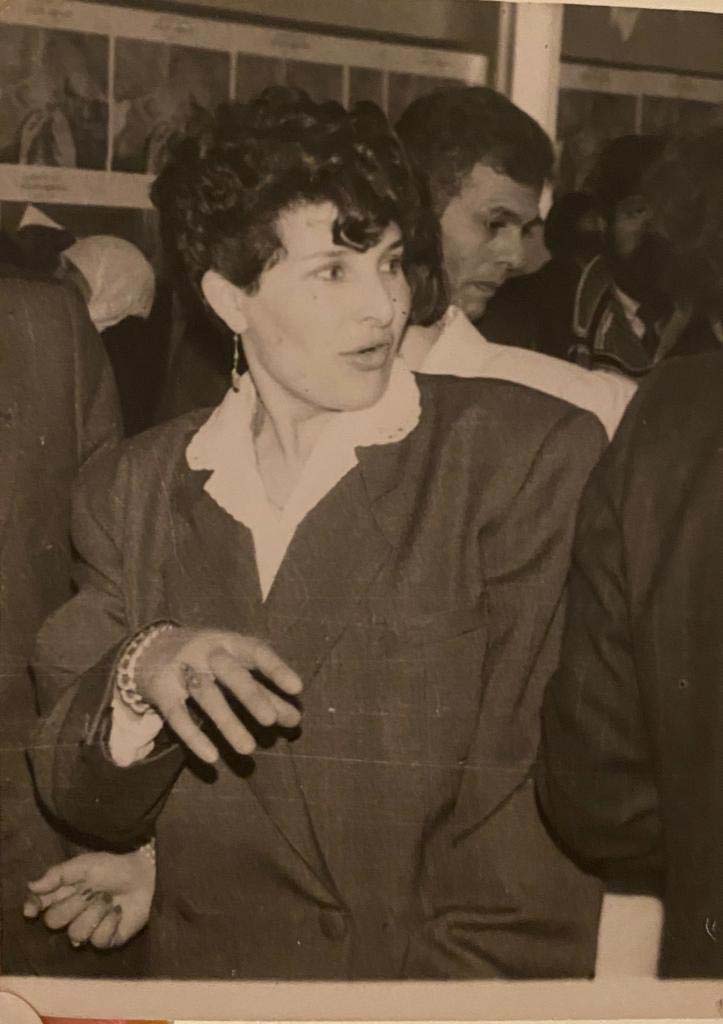

Rabea Kerzabi, who used to work as Algeria’s minister of national solidarity and family in the 1990s, fought to promote women’s education and literacy throughout her career.

“In the 1990s, I co-founded ‘IQRAA’ [the Algerian Literacy Association]. I’ve always believed that literacy is a critical foundation of women’s rights … We opened up classes for women everywhere across the country,” Kerzabi said.

According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, less than half of the female population over the age of 15 were literate during that time. By the year 2015, that number had grown to more than 70 percent of women.

The daughter of revolutionary figure Mohamed Kerzabi, Rabea was inspired to follow in her father’s footsteps.

“He spoke to me about his life, how he’d been tortured by the French, how he was electrocuted to speak out against his fellow [freedom fighters],” said Kerzabi. “All of his stories shocked me. But he made me realise there’s still more that needed to be done.”

“Algerian women especially deserve a lot of credit. We’ve inherited everything we’ve learned from the mujahidates [an anticolonial term for ‘female freedom fighters’] who saved our traditions. It’s thanks to them that we are where we are today,” she added.

“Women are the future. [Algerian scholar] Ibn Badis once said that if you educate a girl, you educate a nation. But if you educate a boy, you only educate one person … It is she who preserves our values; it is she who preserves an entire society.”

The battle continues

Last year, an unprecedented wave of protests swept through Algeria, forcing then-president Abdelaziz Bouteflika to resign. Protesters have since kept up their calls for a complete overhaul of the country’s political system, rallying across several cities every week. Women have played a significant role throughout.

Heddaji, who moved to the United States to pursue her career as a pharmacist in the years that followed the Black Decade, takes note of a shift in attitudes towards women.

“The hirak allows everyone to express their own thoughts – especially women, who were mostly victims from the civil war. I feel that things have changed since, and women are being treated with more respect.”

Freedom fighter Djamila Bouhired was also seen marching alongside demonstrators, which Naili believes to be symbolic: “The dream that these revolutionaries once had [for Algeria] was not really achieved as they’d hoped it to be. It’s almost like a broken promise.”

Amel Boubekeur, a visiting fellow in the Middle East and North Africa programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations, said the hirak has shaped a new era for women.

“It has allowed those who have been excluded from the revolutionary official narratives to create their own revolutionary lineages, and the mujahidates have played a major role here,” she told Al Jazeera.

But for Naili, the battle is far from over.

“It continues,” she said. “Think of the women who keep fighting on a daily basis, those we don’t know. Those who did not have the chance to study, but still made sure her children got an education. The teachers in small villages, or even female bus drivers; they all deserve recognition.”