‘I knew my father would be hanged’: Remembering Nuremberg

The son of a senior Nazi sentenced to death at the Nuremberg trials describes what it was like to grow up in the shadow of his father’s crimes.

On November 20, 1945, several months after the end of World War II, a series of military tribunals began in the German city of Nuremberg.

The first of the trials was the Major War Crimes Trial, in which 22 high-ranking Nazis stood trial in the Palace of Justice. Twelve of the defendants would be sentenced to death.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsThe survivor’s silence: Remembering the Nuremberg trials

Letters to a NaziThis article will be opened in a new browser window

The man behind ‘the biggest murder trial in history’

A further 12 trials – known as the Subsequent Nuremberg Proceedings – were held at Nuremberg between 1946 and 1949.

Seventy-five years after the Nuremberg trials began, we hear from three people upon whose lives the trials and the events that proceeded them cast a long shadow: the son of one of those on trial, the son of one of the prosecutors and the daughter of a Holocaust survivor.

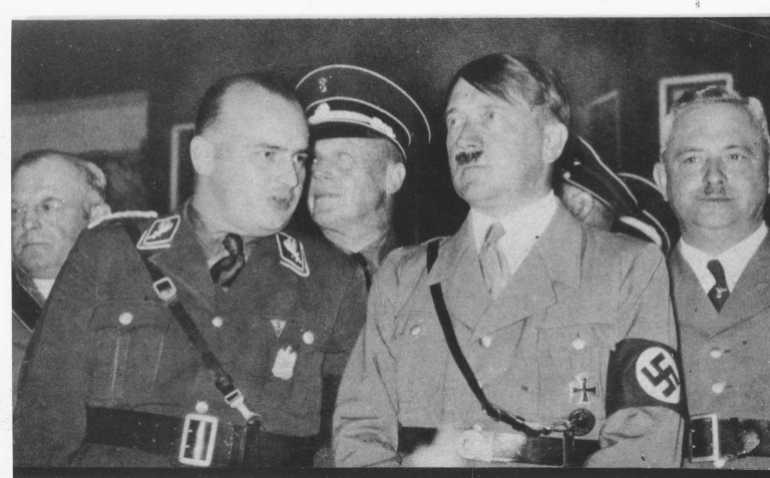

Niklas Frank is the son of Hans Frank, the governor-general of German-occupied Poland during World War II. Known as the “Butcher of Poland”, Hans Frank was convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity at the Nuremberg trials for his role in the deaths of millions of Jews and Poles, and executed.

Here, Niklas, who was born in 1939, describes what it was like to grow up with a father who was a high-ranking Nazi:

I remember visiting my father in the prison in Nuremberg when I was seven years old.

On the other side of the door was Hermann Goring, a very senior member of the Nazi party who was also on trial at Nuremberg (he was sentenced to death but committed suicide hours before he was due to be executed), talking to his wife, Emmy, and their little daughter, Edda.

I sat on my mother’s lap and my father was on the other side of a large window with small holes at the bottom of it, through which we could hear each other talk.

“We will soon celebrate Christmas happily in our house at Schliersee [in Upper Bavaria],” he told me, and I knew he was lying. His lie tore into my heart.

That was my last visit to my father.

There hadn’t yet been a verdict, but his lawyer had visited my mother many times over the summer of 1946 and prepared her for what would happen. It had been a summer full of adventures for me. The American soldiers were friendly and I would run behind them collecting the remains of their cigarettes to take to my mother.

The year before, in the autumn of 1945, I had first seen the pictures in the newspapers – photographs of corpses piled high. Among them were children my own age.

I had known that my father was someone important; we lived in castles, had servants and I thought of Poland as our private property. Then suddenly I learned that my father was somehow connected to these photographs.

I remember my oldest brother Norman, who was born in 1928, going to our mother and saying, “If these pictures are true, our father will have no chance to survive.”

I did not understand what had been going on, but the fact my father was connected to those photographs was deeply disturbing to me.

I had known that we were privileged, that we were not “normal” people, but the war was not that real to me. I recall one time, when I was four or five, sitting in my father’s black Mercedes and seeing a German tank that had been burned. Our chauffeur said “oh that’s a Tiger Tank” and I was thrilled. But I never experienced any bad things, any war things. There was only one time, towards the end of the war, when we were sitting at Schliersee lake and saw an armada of planes on their way to bomb Munich.

The ‘stranger’

One of my most significant memories of my father is from when I was about three years old and we were in Belvedere Palace, where we stayed sometimes.

I was running around a large round table, trying to run into my father’s arms, but he was always just out of reach. My father mocked me: “What do you want Niki [this was what my family called me]? You do not belong to our family. You are a fremdi.” He meant a fremder, a stranger. The implication was that I was illegitimate, that I was not his child.

When you are rejected in this way by your father, you only have two options: You can become a psychological wreck or you can keep a healthy distance from your father, which, subconsciously or by chance, is what I did.

According to a rumour in the family, my presumed biological father was Karl Lasch, the governor of Galicia and one of my father’s closest friends.

Heinrich Himmler, who was the head of the SS, did not like my father and wanted him replaced. But because he could not get Adolf Hitler’s permission for this, he tried instead to hurt people close to my father. Lasch’s father would drive a truck full of stolen goods from Poland to Germany and when Himmler discovered this, he arrested Lasch, knowing that he was my father’s friend. Himmler had Lasch killed in the prison of Breslau.

When my father learned of this, he told my mother, “Now Niki’s father is dead.”

My mother was deeply upset at the accusation and made it clear to my father that it was not true.

My mother had many affairs, but she always aborted those children who were not fathered by Frank. I later learned that she’d had two or three abortions. She would let nothing get in the way of her becoming the “queen of Poland”.

Shopping in the Krakow ghetto

My mother would go to the Krakow ghetto to buy fur and expensive cloth that her personal tailor would make into clothes.

I recall one occasion when I was about four when I was sitting in the back of the car with my nanny, Hilde, during one of my mother’s shopping trips to the ghetto.

Near the car was a boy of between eight and 10, looking at me in a very sad way. I stuck out my tongue at him. He didn’t respond; he just walked away. I felt triumphant towards him, but Hilde pulled me back. I didn’t understand where we were.

My mother was very cold. Like my father, she didn’t care about the death and misery of others. She just enjoyed her life – the dinners with guests, the shopping trips.

My mother was the one with the strong personality. We all feared her. My father was weak in comparison. When I later interviewed the American priest, Father O’Connor, who baptised my father into the Catholic Church during his imprisonment in Nuremberg, he told me, “Niklas, I have to tell you one thing: even in prison your father was still afraid of your mother.”

At one point during the war, my father, who had reconnected with the great love of his life from his youth, wanted to divorce my mother. He asked Hitler for permission, as was, I think, required of senior party members, but Hitler forbade it until the war was over. My mother, learning of my father’s wish, wrote to Hitler, sending him a photo of her and her five children, and asking why would a husband leave such a beautiful family?

‘You poor boy’

After my father was arrested in May 1945, our circumstances changed dramatically. The Americans moved us into a two-room flat. We didn’t have any servants or any money. It was a long fall from grace. But for me it was a great adventure. I had freedom, I could fish and there were deadly weapons left behind by fleeing SS soldiers to play with.

My mother tried hard to feed us. She was always making deals, exchanging everything – particularly stolen jewellery – for bread. It was the toughest time of her life, but she never gave up, complaining only in letters she wrote to my father in prison.

For me, being the son of a mass murderer brought many advantages. “Oh you poor poor little boy,” people would say. “What happened to your poor innocent father? What do you want to eat and do you have enough money?” At that time, there were only advantages in Germany if your father was hanged as a high-ranking Nazi.

I oppose capital punishment, but I am happy that my father got to experience the fear of death that he himself had inflicted upon so many innocent people.