The Chase Key: How a Black man died of dehydration in a US jail

The 2016 death of Terrill Thomas in Milwaukee exposes how inmates with mental illnesses fail to get adequate care.

Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA – Milwaukee County Jail staff were not entirely sure what to make of 38-year-old Terrill Thomas when he arrived for booking on April 16, 2016.

Thomas faced seven charges including felony possession of a firearm, reckless endangerment, armed robbery and trespassing. He was arrested after firing a gun inside Potawatomi Bingo Casino in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. “He was facing 63 years,” said his son, Terrill Barnes.

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘Can’t give them jobs’: Rwandans grapple with fears over UK asylum plan

‘It feels personal’: Residents fight Melbourne tower block demolition plan

‘Children of the Ganges’ — The boatmen of India’s Varanasi

But some jail guards also suspected the 196cm (6.5-foot), 136kg (299-pound) man’s joyous, mostly incoherent rambling, were signs of a mental illness, prompting authorities to place him in a unit specific to his needs.

In the days that followed, Thomas continued to exhibit signs of mental distress. He flooded his cell, prompting his transfer to a new unit where his water was shut off. Thomas also refused to eat.

Less than eight days later, Thomas was found dead.

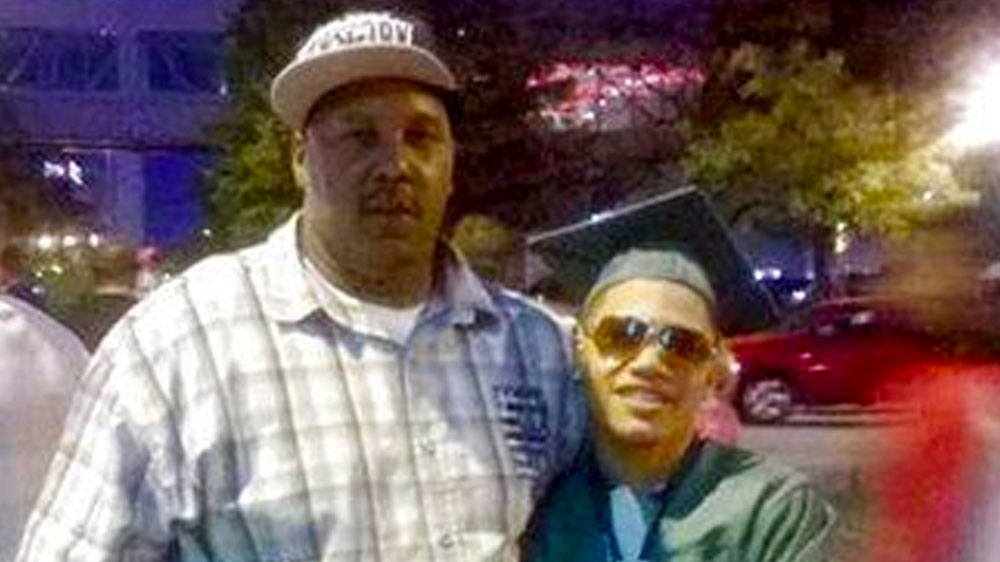

![This undated photo provided by family lawyer on May 2, 2017, shows Terrill Thomas [Family handout/AFP]](/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/88578d67a80942c5ad23c7a1acc77c0d_6.jpeg)

Since then, Thomas’s case has exposed the failures of the Milwaukee County Jail (MCJ) – and facilities nationwide – to adequately provide care for inmates with mental disorders. It has also highlighted the liability concerns involved in outsourcing inmate healthcare to for-profit companies to cut costs.

The contract

The MCJ and the Milwaukee County House of Correction has a long, troubled history of providing inmate healthcare. In 1996, Milton Christensen, along with other inmates, sued the MCJ, alleging the conditions in the facility were “substandard”, led “to the infliction of needless pain and suffering”, and “created a threat to the inmates’ mental and physical wellbeing”.

The lawsuit was settled in 2001. The settlement said the jail and house of corrections must meet a number of requirements related to inmate care under a consent decree, also known as the “Christensen Decree”. These include eliminating over-population and providing access to adequate healthcare.

In 2008, a Wisconsin Appeals Court held the MCJ in contempt for violating the decree, citing overcrowding and not providing inmates with a bed within the 30 hours required. For at least five years after the 2001 settlement, Milwaukee County was never found to be in full compliance with the decree, according to local media. These difficulties were compounded by targeted budget cuts to the county as a whole by state and county officials.

In 2009, the then-County Executive and candidate for Wisconsin governor, Scott Walker, cut $10m from the Milwaukee County budget through vetoes against aspects of the budget. Walker touted cuts as “surgical” and hoped the moves would stimulate privatisation of county functions.

At the time, David Clarke was sheriff, overseeing every aspect of the county jails. Before eventually rising to national prominence as the cowboy hat-wearing, anti-Obama, right-wing sheriff, Clarke used the budget cuts to begin advocating for outsourcing inmate healthcare to private companies. His number one choice was Armor Correctional Health Services.

Founded in 2004, the Florida-based medical company currently provides medical care for more than 40,000 inmates in eight states, according to Armor’s website. Clarke relayed his strategy to bring in Armor via email with his second-in-command, then-Inspector Richard Schmidt. According to emails from September 2011, obtained by Al Jazeera through an open records request, Schmidt and Clarke strategised on how to get Armor a deal with the county, acknowledging there would be pushback.

“The ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union), Legal Aid, and Dr. [Ronald] Shansky will do whatever they can to stop Armor Medical from a contract. Dr. Shansky totally opposes their staffing plan, calling it negligent,” Schmidt emailed Sheriff Clarke. “If we intend to fight for Armor, the ACLU will take this to court and stop the process.” Schmidt states in the email that ensuing delays in a contract due to court battles “will essentially leave a $500,000 to $1,500,000 hole in the 2012 budget.”

By that time, Armor had faced lawsuits over its services in Broward County, Florida’s Fluvanna County, Virginia, as well as in several other states.

Read more: Who is David Clarke?

Clarke brushed off Inspector Schmidt’s concerns. “It won’t leave a hole,” Clarke emailed back. “[County] Board will have to come up with the money to offset it. It’s why we go the budget route instead of a stand alone approval that has no budget implications. We’re not asking them to spend added money to do it; we’re presenting it as a way to SAVE money.” Confidently, Clarke emailed: “We’ll be fine. I really don’t care if the Board rejects … where are they going to find the money to offset? If they reject with no added funding, we hand them back a deficit. That is not spending money we don’t have. When they ask for a budget correction plan we hand them back the Armor plan. In the end, they will get the built-in deficit back. Get it?”

The county also had warnings from residents and healthcare providers alike. Candice Owley, then-president of the Wisconsin Federation of Nurses and Health Professionals (WFNHP), testified to the county board in 2012 that the county should “take time to do a thorough review [of Armor] before terminating over 100 jobs of dedicated professionals and further endangering the case of lives of inmates”. The WFNHP presented a report to the county titled, Bribery and Bad Medicine? (PDF), highlighting cases against Armor.

But those warnings appeared to ring hollow, as Clarke continued to push for Armor to get the contract. In 2013, Armor was awarded its first contract. Three years later, Thomas would end up dead while in Armor and the county jail’s care.

The arrest

Thomas was not new to imprisonment but worked hard to overcome his past. He was in and out of jail on drug, firearm and other charges. After being arrested for having warrants, operating a vehicle with a suspended licence and assault in 2008, Thomas started planning a new future, his family said.

“Him being in jail all those years helped him realise what’s important,” his son, Terrill Barnes, told Al Jazeera.

Shortly after completing his last prison sentence, Thomas opened a car lot with his former cellmate. “He loved life,” Terrill Barnes said, adding that his father had a passion for luxury cars.

In 2016, Thomas travelled to Atlanta, Georgia, to buy three cars for the lot. Not long after returning home, the Mercedes-Benz he had just bought was stolen.

“This is basically what triggered him off to do everything that he did,” Terrill Barnes said. Thomas disappeared for days attempting to locate someone he suspected was the thief.

Thomas’s mother asked the police to step in, fearing he might do something dangerous. Thomas suffered from mental illnesses, including bipolar disorder. Police, however, told her Thomas first had to do something illegal. It is not clear if she informed officers of his mental health condition. Thomas resurfaced after a few days, briefly speaking with his two sons at their grandmother’s house.

“The last time I talked to my father he was sitting in the car,” Terrill Barnes recalled. He said at one point his father told him: “It gets spooky at night son”. Confused, Terrill Barnes took this as a sign that his father “was starting to lose it”.

Minutes after speaking with his son, Thomas saw the suspected thief standing outside his mother’s home, Terrill Barnes said, adding that his father fired a pistol into the air before adjusting his aim. Rounds struck one person in the crossfire, who survived. Thomas disappeared again. A day later, Terrill Barnes woke up to the news of a man firing a gun inside Potawatomi Bingo Casino.

It was not long before he realised it was his father.

The chase

When Thomas entered the Milwaukee County Jail in April 2016, he was placed in Pod 4C, the unit for inmates with mental illness and special needs.

Thomas flooded his cell by clogging its toilet. Jail guard Lieutenant Kashka Meadors was called to respond to the incident, along with other lower-ranking correctional officers including James Ramsey-Guy. Thomas was moved to Pod 4D, a disciplinary unit used to isolate inmates who were disruptive or could not be held in the general population. In 4D, inmates were kept in solitary confinement, with only very limited access to recreation and privileges.

Valerie Becke, a psychiatric social worker who worked for Armor in 2016, told Al Jazeera being in 4D is like “having to be in your bathroom for 12 hours”. She described it as “dark, and gross, and loud”.

“Certain inmates would know by the sound of your shoes who’s coming. It was the craziest thing,” she said.

”[4D

having to be in your bathroom for 12 hours.”]

Ordered by Meadors, the water to Thomas’s cell, controlled by a system known as “the chase”, was shut off. Several guards, speaking to Milwaukee Police Department (MPD) detectives in 2016, said this was a common preventive measure. The water shutoff was not recorded in the jail log, which included important information to be passed between staff from different shifts. Officer Ramsey-Guy told investigators in 2016 water shutoffs happened “so often” that it was “not always noted in the jail log”.

Meadors informed her supervisor that Thomas flooded his cell and was transferred to 4D. She left Thomas in the hands of guards assigned to the unit, according to investigative reports. She told investigators she did not check to see if Thomas’s water had been turned back on because after moving him to the unit, he was the responsibility of guards in 4D.

Over the course of the next five days, Thomas would repeatedly slam his hands or flip flops against his cell’s walls, talk to himself, pace his cell or stare blankly, according to surveillance video and investigative reports, which cited interviews with inmates in nearby cells and some correctional officers. His water was never turned back on.

Marcus Berry, then a 28-year-old inmate in a nearby cell, told investigators in 2016 that Thomas’s behaviour was impossible to ignore. He said Thomas never spoke as nurses checked his blood sugar levels and blood pressure. Berry also said: “He never saw anyone bring Thomas anything to drink in the entire seven days he was there.”

Berry said on one day at about 4:30pm, a correctional officer working the desk allegedly refused to give Thomas water because he was “the only CO” on duty. The next shift told Berry at 7:00pm: “He’s lying here asleep, he doesn’t need water if he’s asleep.” Barry told investigators that he told the correctional officers: “If this man dies, his blood’s gonna be on your hands”. Broderick Summerville, another inmate, told investigators a nearly identical story.

Berry said Thomas at one point was “dizzy and not able to stand, weak in the knees, and drowsy”.

Thomas was unable to be moved from the jail to the courtroom for a hearing on April 20, so officials took the unusual step of trying to hold the hearing outside of his cell. His nude, non-verbal disposition bothered the attorney, who requested a competency evaluation. It is unclear if the evaluation took place.

Correctional Officer JorDon Johnson told police investigators he recognised Thomas while doing his rounds. Johnson knew Thomas from the neighbourhood and lived next door to his mother for years. He tried unsuccessfully to address Thomas by his nickname, T-Buck, and asked why he had been arrested. Johnson later told detectives from the MPD that he felt Thomas’s behaviour was uncharacteristic and “not right”.

Correctional Officer Jeffrey Harley and Psychiatric Social Worker for Armor Correctional Ja-kal Walker both also told investigators they felt Thomas had suffered from a mental illness. Walker told police investigators she observed Thomas throwing his mattress around his cell, and either ignored her or could not respond. Checking his file, Walker noticed he was scheduled to see a psychiatric nurse practitioner “in the near future”, investigative reports said.

Detectives in 2016 also noted inconsistencies in Thomas’s medical charts. Two nurses who were grilled by detectives following Thomas’s death said the inconsistencies were because the times noted reflected when the information was put into the computer, not when the information was collected. The inconsistencies were compounded by the communication issues reported by MCJ and Armor officials.

Thomas was found unresponsive in his cell on April 24. Despite life-saving measures, he was pronounced dead at 1:57am.

The aftermath

The initial cause of Thomas’s death was listed as “unknown”, but four months after Thomas was found in his cell, the Milwaukee County medical examiner ruled his death a homicide and said he died of dehydration.

The conclusion prompted calls for an investigation and justice. At the same time, racial tensions across the US and in Milwaukee were coming to a head. The 2016 police killing of a Black man in Milwaukee led to days of unrest.

Seven correctional officers were initially charged with wrongdoing as a result of Thomas’s death. The list eventually narrowed to three: The jail’s Major Commander Nancy Evans, Meadors, and Ramsey-Guy, who each reached plea deals that significantly lowered the charges they faced. They were given sentences ranging from 30 days to nine months in prison.

Others, however, were not charged, including high-ranking officials that community members said deserved punishment. Among them was Sheriff Clarke, who resigned in 2017 as the investigation into Thomas’s death started gaining traction and dehydration was identified as the cause of death.

Clarke, who after resigning appeared regularly on Fox News and advised a pro-Donald Trump super PAC, did not respond to Al Jazeera’s repeated request for comment. In 2017, Clarke told the Associated Press News Agency he had no comment on a civil lawsuit filed by the family related to Thomas’s death. Instead, he commented only on Thomas’s criminal background.

“I have nearly 1,000 inmates. I don’t know all their names but is this the guy who was in custody for shooting up the Potawatomi Casino causing one man to be hit by gunfire while in possession of a firearm by a career convicted felon?” Clarke told the news agency. “The media never reports that in stories about him. If that is him, then at least I know who you are talking about.”

Charges were also issued related to medical staff employed by Armor. Investigators called medical entries made by Armor’s staff “complete fabrications”. Three Armor staff members were named – but not charged – in the first criminal complaint against Armor in the Thomas case. Under Wisconsin laws allowing corporations to be charged as people, Armor itself faces seven counts of intentionally falsifying medical records.

The company also faces a single count of abusing an inmate. Under the felony charge, Armor “may be fined” no more than $10,000. No employees face jail time and Armor has tried to disconnect itself from their actions. The company denied investigators’ assertion that falsifying records was a “corporate practice”.

Armor has not responded to Al Jazeera’s repeated requests for comment.

“This is not a reflection of Armor’s culture,” the company said in a statement to local media in 2018 once its role in the death went public.

But the company also faced lawsuits elsewhere. The year Thomas died, Tulsa Oklahoma terminated its own contract with Armor. This shadowed the resignation of Sheriff Stanley Glanz, cited in a related lawsuit against Armor. Glanz left behind a reputation of corruption, including “going as far as to condone the falsification of medical records in an effort to hide deficient care”. A separate Tulsa lawsuit called Armor’s medical record disorganisation “flat out crazy”.

The same year, an inmate who suffered from mental illnesses died due to starvation under Armor’s supervision at a Broward County, Florida, jail. The family filed a lawsuit against the county, which settled in the case. Armor said it would “aggressively defend” its employees.

Four more deaths also occurred in 2016 in New York jails. Both occurred in solitary confinement. One was ruled hypothermia, the other “patient abandonment”. An evaluation of Armor by New York State later revealed a wide range of systemic issues. As a result, New York banned Armor from bidding on contracts for three years.

After Thomas’s death, Armor stayed in Milwaukee County for more than three years. The company’s contract ended in May 2019. It was replaced with the private inmate healthcare company, Wellpath.

A 2018 Milwaukee County audit of Armor found the company never met the required 95 percent staffing level it needed to keep its $16m contract. This deficit spanned a 22-month period during which the county conducted the audit between November 2015 and August 2017. County Supervisor Sheldon Wasserman told the Urban Milwaukee daily publication in March 2019 he felt the penalties Armor faced as a result of the audit, separate from the Thomas case, “were a little low”.

The vague language in Armor’s initial contract did not require the company to report staffing levels. Its employees, the audit found, failed to record blood test results or ensure inmates swallowed their medication. Incomplete refusal of treatment forms were also signed off by Armor staff.

“Medical staff have a responsibility to check on people,” said Becke, the psychiatric social worker who worked for Armor in 2016. “If you know someone’s water is off, you have a liability to check on that person.”

He was a helper, a giver. He wasn't a bad person at all.

In May, Armor and Milwaukee County paid $6.75m to settle a lawsuit by Thomas’s family.

Thomas’s lawyers said it was the largest jail death settlement in the history of the state.

“This settlement reflects not only the profound harm suffered by Mr Thomas and his family, but also the shocking nature of the defendants’ misconduct in shutting off this man’s water and ignoring his obvious signs of distress as he literally died of thirst,” the lawyers said in a statement at the time. As agreeing to a settlement limits his family’s ability to further comment on the case, Thomas’s family has retreated from public view to rebuild after his loss.

“He loved life, he loved everything in it,” Terill Barnes told Al Jazeera a year after his father’s death.

“He was a helper, a giver. He wasn’t a bad person at all,” he said, adding that he hopes those involved in the case “always remember to live truthful, even people who are wrong in this situation. I hope they can take this situation and make their lives better”.