Young, educated and jobless: The struggles of India’s graduates

Recent studies show that people with degrees find it harder to land jobs than those without.

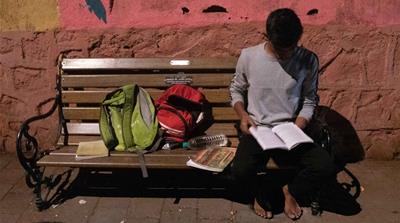

Mumbai, India – Down a dimly-lit backstreet known locally as Study Lane in central Mumbai, India‘s financial capital, Rohit Singh can frequently be found poring over his textbooks. He is trying to get into an expensive Masters in Business Administration (MBA) programme. And he is not alone; dozens of other students also study there, oblivious to the loud motorbikes tearing along the small road.

“If I get admitted to a good MBA college, then I’m sure I will get a better job,” the Bachelor of Commerce student told Al Jazeera. “So many people are graduates these days that it’s hard to see how either the private sector or the government can provide enough employment.”

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsBoeing hit with 32 whistleblower claims, as dead worker’s case reviewed

US imposes new sanctions on Iran after attack on Israel

A flash flood and a quiet sale highlight India’s Sikkim’s hydro problems

Singh, 21, and his friends along Study Lane feel they need to stand out in India’s increasingly competitive job market, and this place offers them a chance to focus and compare notes. He also says he is escaping the distraction of his mother’s TV.

But recent evidence suggests that a sterling education record is no longer the guarantee to a good job it may once have been. Poor education standards and burdensome corporate regulation are just two of the reasons why jobs remain hard to come by for India’s graduates despite enviable economic growth rates.

According to a report released this year by the Azim Premji University’s Centre for Sustainable Employment, people with a graduate degree are more than twice as likely to be unemployed than the national average. The findings are based on surveys of 160,000 households across the country. The report also says women are more likely to be unemployed than men.

Many of the students down Study Lane are the first ones in their families to ever go to university. Government figures show the proportion of India’s 18 to 23-year-olds enrolled in higher education has more than doubled to 25.8 percent from 12.6 percent in 2004. India’s government hopes this figure will rise to 30 percent by 2020.

The informal sector

Yet, unemployment remains a major hurdle for the Indian economy and became a major issue for Prime Minister Narendra Modi in this month’s election as he sought a second term.

In February, the Business Standard newspaper published a report that it said was based on leaked government figures showing that unemployment had hit a 45-year high of 6.1 percent. Minister of Finance Arun Jaitley first said the figures were “not final” and later described the report as “disinformation”. But many analysts say the data supports anecdotal evidence.

One of the main reasons graduates and people with postgraduate degrees find it hard to land jobs is the large size of the so-called informal economy, analysts say.

More than 80 percent of Indians work in jobs without regular pay or social benefits, according to the International Labour Organization. In the cities, they are employed as street vendors, construction workers and in mom-and-pop shops, or as labourers on farms and in fields. The World Bank says agriculture accounts for 42 percent of the workforce.

Analysts such as Amit Basole, head of the Centre for Sustainable Employment and an author of the Azim Premji University survey, told Al Jazeera that insufficient job creation in the private sector has meant that the growth of high-skilled jobs has lagged behind that of the overall economy.

The failure to develop a large manufacturing base has been a “big disappointment”, he added, explaining that such industries could have generated jobs “across the skill spectrum” and absorbed “huge increases on the supply side of the labour market”.

Jayati Ghosh, an economics professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi said India has lagged behind places like South Korea, Taiwan and China, where governments have invested heavily in manufacturing, infrastructure and providing companies with access to credit.

‘Openly unemployed’

Graduates are also becoming more selective. Rising expectations mean many graduates are holding out for jobs that match their qualifications, Ghosh told Al Jazeera.

“As you get higher up the education scale, people are more willing to be ‘openly unemployed’. If there’s no jobs available and you’ve done your BA degree, you’re not going to then become a rickshaw driver. It doesn’t make sense for them,” she said.

For those graduates who decide to take up low-skilled work, the competition can be intense. The government remains a major source of such jobs. In a recent case reported by Indian media, nearly a third of the 93,000 applicants for 62 police courier jobs in the state of Uttar Pradesh had doctorates.

Government jobs provide security, benefits, and relatively good pay. Minimum salaries are currently set at 18,000 rupees ($259) a month, while 67 percent of the workforce earn less than 10,000 rupees ($144).

But for graduates like Singh, that’s not good enough. He says he wants to work for a multinational company, which he hopes will pay more than the 30,000-40,000 rupees ($430-$575) monthly wage his father earned.

But even if he succeeds in earning his MBA from a local university, future employers may still question the quality of his education.

In a recent survey by Aspiring Minds, a skills assessment and research firm, employers said 80 percent of Indian engineering graduates did not meet the minimum requirements of the companies looking to hire them. Many such firms say prospective candidates lack sufficient industry experience because their courses are too theoretical.

Poorly-trained teachers, an exam system that rewards rote learning and teaching institutions that don’t meet the needs of industry, are some of the reasons graduates face a skills deficit, says Varun Aggarwal, cofounder of Aspiring Minds.

“Few graduates have done internships or heard an industry talk and few professors discuss industry applications for the skills they teach,” Aggarwal told Al Jazeera. “We found over 90 percent of engineering graduates are not even able to write ten lines of code,” a major reason why many large companies are investing in sizeable training campuses and three- to six-month long bridging courses.

The government has tried to offer alternatives to the typical college or university route through skilling and vocational training programmes like the National Skill Development Corporation and Skill India scheme. But with a lack of available data and follow-up surveys, experts have found it difficult to assess their effect.

“We do know, however, that the emphasis has been on meeting targets and pushing people through the programme, with no clarity on them securing jobs or gaining employable skills,” says Basole of the Centre for Sustainable Employment.

Despite the odds apparently being stacked against him, Singh remains optimistic that an MBA and good old-fashioned hard work are his tickets out of the backstreets of Mumbai. “My father has always told me one thing – whatever you do, do it well and you will be fine,” he said.