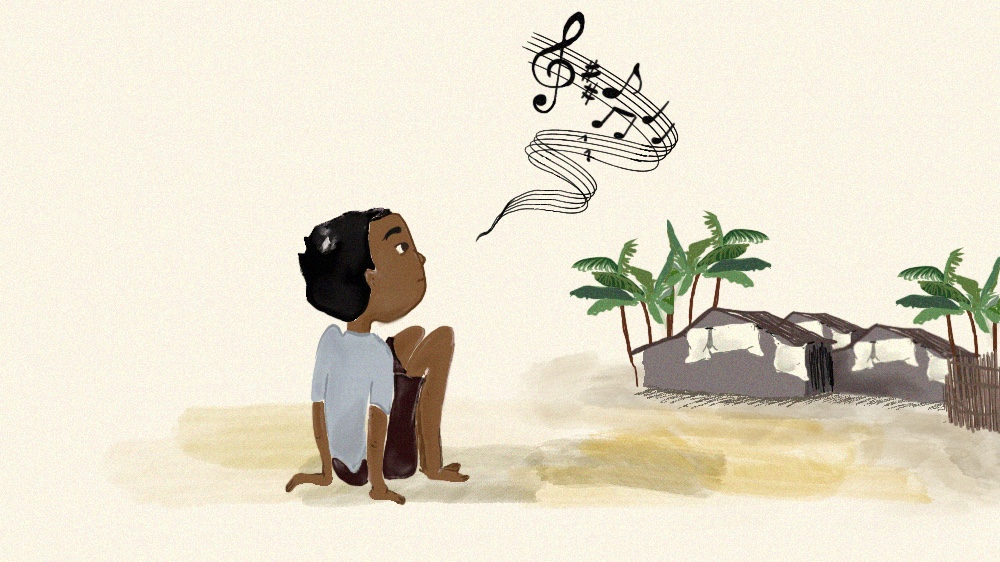

A boy who can sing: The life of a Rohingya child refugee

In the Kutupalong refugee camp in Bangladesh, 10-year-old Kassem sings about the suffering of his people.

Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh – The sun was burning over Kutupalong camp, the largest refugee settlement in the world. It was midday, so hot that it was hard to breathe.

I was looking for a child to sing Rohingya songs for a film I was making about the history of the Rohingya in Myanmar, searching among the endless makeshift huts that seemed to stretch to the horizon.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsConflict, climate, corruption drive Southeast Asia people trafficking: UN

Bodies of three Rohingya found as Indonesia ends rescue for capsized boat

How is renewed violence in Myanmar affecting the Rohingya?

This used to be a forest. But the trees have been cut down to make space for the more than one million Rohingya refugees who live here, many having fled what the UN described as “ethnic cleansing” in Myanmar.

Now this former forest, which was once a favourite honeymoon destination for Bangladeshis, is full of people carrying construction materials, food supplies and water; full of tiny huts; full of sorrow and loss.

I searched for the child among them, not knowing who that child would be, but sure that I would know when I found them.

On my second day in the camp, I came across a large tree with a small makeshift shop beneath it, selling chewing gum, sweets, cigarettes and packets of crisps that have passed their sell-by date.

The shopkeeper kept a watchful eye on a group of young boys who were deep in conversation nearby.

The boys were aged between seven and 11. Some were dressed in school uniforms; others wore just shorts. All of them were barefoot.

‘No shoes’

This is how I met Kassem. He was a diminutive 10-year-old, a quick thinker with large, intelligent eyes and a cheeky sense of humour. He spoke on behalf of his group and knew a few words of English.

“Where did you learn them?” I asked.

“At work in the army barracks,” he replied, matter-of-factly. “I work as a waiter there.”

I asked if he goes to school.

There are about 75 learning centres run by the UN and NGOs in the camp, but there is a severe shortage of qualified teachers and the facilities are often basic and run down.

“Sometimes, I need to earn some money,” he said. “So it is more interesting to work in the army barracks.”

The camp is guarded and policed by the Bangladeshi army and there are a few army stations inside it.

As Kassem spoke, some of the other boys slowly started to open up and join in until they were all talking at the same time.

I asked them what games they liked to play.

“Football,” they answered in unison.

“Show me,” I said.

The boys looked hesitant. Then Kassem spoke. “We don’t have a ball,” he told me.

I asked them to wait and went to find a shop that sold toys. It took half an hour to find one and the ball I eventually purchased was far from ideal but when I returned to the waiting boys, their eyes lit up when they saw it.

They led us through the narrow alleyways of the camp to a small patch of land nestled between huts and piles of rubbish.

Within 10 minutes, two teams had formed and a game had started. More children appeared and joined in. Spectators gathered along the imaginary touchline, cheering the barefoot players on. In the middle of it all was Kassem, leading the game, telling players what to do and deciding who would be in which team.

In the little over a month I spent in the camp, one thing stood out more than anything else: I never saw a child wearing shoes. During the dry season, the heat was unbearable and the ground scorching, during the monsoon season, it rains non-stop and the camp’s roads are flooded. But never in that time did I see a child wearing shoes.

Later, when I returned to London, I showed my children my video of the boys’ football match.

“Mama, why don’t they wear any shoes?” they asked with surprise.

“Their parents are too poor to afford them,” I replied.

My boys still did not get it. “No shoes at all?”

“No shoes,” I answered them.

“But it’s impossible to play football barefoot,” they told me.

“Why don’t we try to see how it feels?” I said. We did try – in our local park – but they did not last long.

It was difficult to explain to them that in a place where people have lost everything, where adults must struggle to provide the most basic of things – food and shelter – as they grapple with their own pain and trauma, something like shoes can be an unattainable luxury.

A song of pain and loss

Every day after that first day, I would look for Kassem. He was never easy to find. Sometimes even his father would not know where he was. But from time to time, some of the other children would help me locate him.

One day, I spoke to Kassem’s father, Abdulrahman, about what had happened to their family back in Myanmar. He described how, one night in July 2012, their village in Rakhine state had been attacked by the Myanmar army and a mob of local Rakhine villagers. Their house was set on fire. Kassem’s mother, Abdulrakhman’s wife, had been inside it at the time. She never made it out.

When Kassem felt more comfortable with me and the film crew, I asked him about his life back in his home village.

They had a good house, he told me, “not small and horrible like now.”

“We had some gold, we had land; now we have nothing.”

“What happened to your house,” I asked.

“We were attacked by an angry mob,” he explained. “It was a bloodbath.”

“Our house was set on fire. My father took me and my three brothers and ran to the jungle. My mum was not well, and she stayed behind.”

He paused.

When he spoke again, he said: “From the jungle, we watched what was happening to our village and our house. It burned down.”

I did not ask anything else.

But Kassem was eager to talk about their escape – their weeks-long journey as they tried to cross the jungle at night, avoiding the army; how hungry they had been; the bugs that had bitten them and how, when they had eventually reached Bangladesh, one man had given them some food and water.

“There is no better person than that man,” he declared.

I asked him if he knew any songs in the Rohingya language.

He told me he did.

“Would you sing it for my film?” I asked.

He started singing – a song about Arakan, the former name of what is now known as Rakhine state, a song about home, about the suffering of his people, a song of pain and loss that transcends language.

I had found the child who could sing.