Guru Nanak and the promise of an inclusive Pakistan

Pakistan reimagines its relationship with its Sikh heritage by opening a key corridor and restoring sites of worship.

![ONLY FOR ESSAY: Guru Nanak and the promise of an inclusive Pakistan [DON''T USE]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/a83bc1742b33464996b2c429ff4aa1d9_18.jpeg?resize=770%2C513&quality=80)

Pakistan – For a few days every November, the Pakistani city of Nankana Sahib is transformed as thousands of Sikhs and other devotees of Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, descend upon it to celebrate Guru Nanak Gurpurab, the anniversary of his birth.

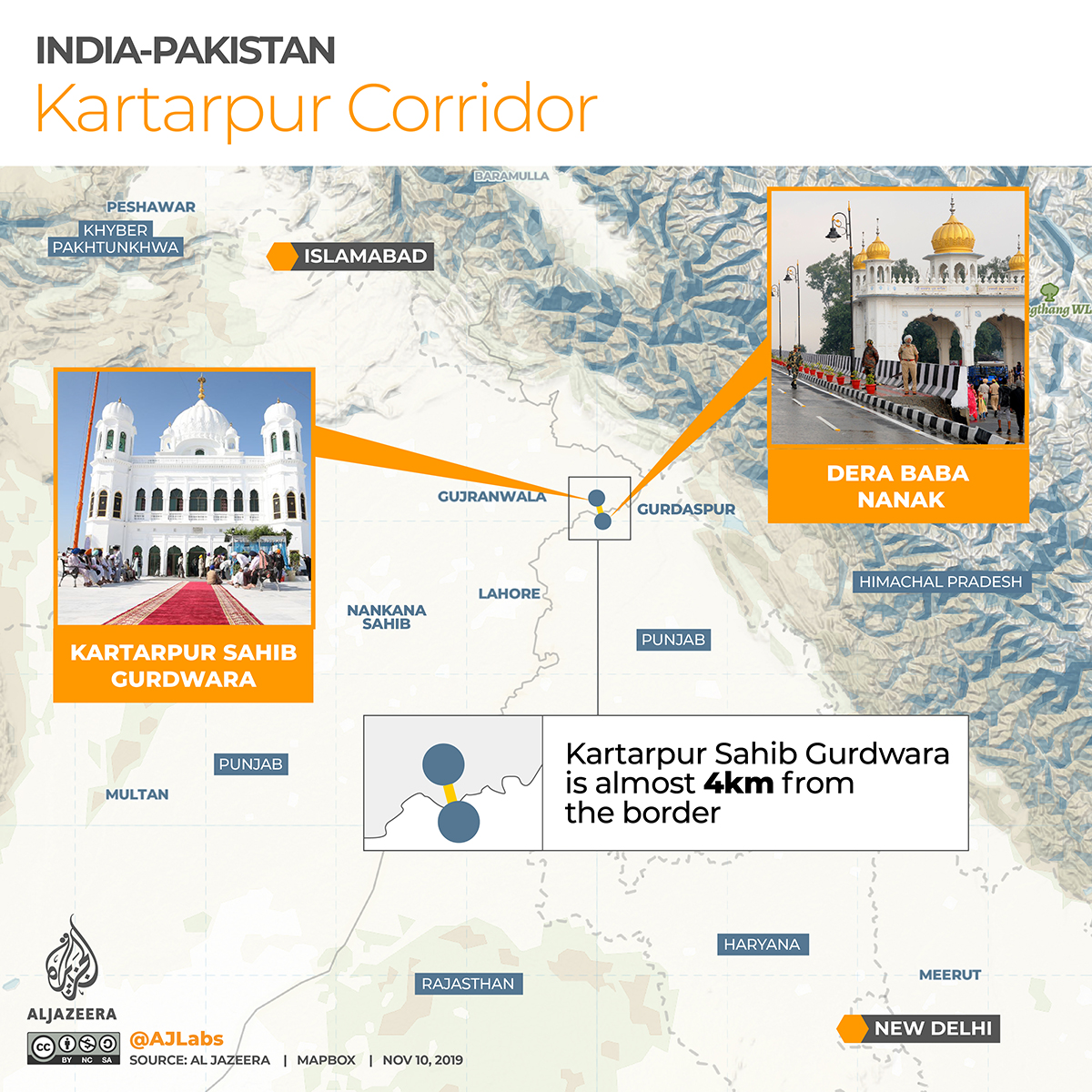

They come from within Pakistan, from the Middle East, Europe, the United States and Canada, but the majority arrive from neighbouring India. This year – on his 550th birthday – the numbers are likely to be even greater. On Saturday, as part of the celebration, Pakistan opened a corridor that will allow Indian pilgrims to travel without visas between the Indian town of Dera Baba Nanak and the Sri Kartarpur Sahib Gurdwara, Guru Nanak’s final resting place, about 6km (4 miles) away in Pakistan.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMuslim pupil loses UK court bid over Michaela school prayer rituals ban

Photos: Sikhs celebrate harvest festival of Baisakhi, marking new year

Masses gather for Eid celebrations in India

Men in colourful turbans and dangling kirpan (a knife or sword) and women in saris – once a regular sight in the cities and towns of what came to be known as West Punjab – will become so again. The sound of Sanskritised Punjabi and the drone of kirtan (devotional songs) from the loudspeakers of the city’s gurdwaras will mingle with the azan, the Muslim call to prayer.

Nankana Sahib

Located about 75km from Lahore, Nankana Sahib was once known as Rai Bhoi Di Talwandi, but was renamed in honour of Guru Nanak, who was born there in the 15th century.

Gurdwara Janam Asthan, a vast and imposing complex with large manned gates located at one end of the main artery that runs through the city, marks the spot where Guru Nanak was born.

On the city’s eastern side is Gurdwara Balila, where he played as a child.

While Gurdwara Janam Asthan remains the main focus for pilgrims, over the past few years, several smaller gurdwaras that had been in ruins for decades have been renovated.

These gurdwaras tell a story of a state reimagining its relationship with its Sikh heritage and actively trying to preserve it.

![ONLY FOR ESSAY: Guru Nanak and the promise of an inclusive Pakistan [DON'T USE]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/a83bc1742b33464996b2c429ff4aa1d9_18.jpeg)

Partition and the Sikhs of Punjab

Carved out of colonial India during independence from Britain in 1947, Pakistan was intended as a home for the Muslims of South Asia, in contrast to Hindu-dominated India. But in this battle between Hindus and Muslims, the Sikhs of Pakistan found themselves in a precarious position.

The partition led to the largest mass migration in human history and the deaths of at least a million people.

The Sikhs of Punjab, the only province other than Bengal that was divided between India and Pakistan, were not left unscathed. Riots broke out between Sikhs and Muslims, with each community committing acts of brutality against the other.

Many Sikhs fled Pakistan for India, and overnight some of the most sacred religious sites associated with Sikhism, including Nankana Sahib, were abandoned. They quickly fell into disrepair or were taken over by refugees fleeing the violence.

But partition, which had been imagined as a solution to the communal issues of India, did not bring an end to the animosity. With Kashmir becoming a particular point of contention, the neighbours remained at odds. They have fought three wars and countless skirmishes since.

In this charged political environment, Sikh heritage fell victim to neglect and, sometimes, hostility. So, too, did some Sikhs and Hindus living in the areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, formerly known as North West Frontier Province, the most westerly province of Pakistan which borders Afghanistan. The riots during partition did not reach there. But during the wars with India in 1965 and 1971, many were forced from their villages. Some headed for Nankana Sahib, about 500km (310 miles) away.

![ONLY FOR ESSAY: Guru Nanak and the promise of an inclusive Pakistan [DON'T USE]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/7c630c9833b64c848bcababbe602872f_18.jpeg)

When, as part of my research for my books A White Trail and Walking with Nanak, I spoke to some of the first Sikh families from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to have moved to Nankana Sahib, they told me how, upon their arrival, they found Gurdwara Janam Asthan in a state of disrepair; its sacred pond empty and its gardens overgrown. Other, smaller, gurdwaras were in a far worse state.

Finding refuge in the abandoned gurdwaras of Nankana Sahib, these Sikh families began some of the earliest renovation work – at their own expense. As, over the years, more Sikh families moved from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to Nankana Sahib, a small Sikh community began to emerge.

The numbers increased exponentially after 9/11 as the Taliban sought sanctuary in parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and began targeting religious minorities. Some reported being asked to pay jizya (a tax levied on non-Muslims living in a Muslim state) and forced from their homes if they did not. In 2010, a young Sikh man named Jasper Singh was beheaded when his family could not pay. There were other high-profile killings of Sikhs in the region.

From a handful of families, the number swelled to several hundred. For the first time since partition, a sizeable Sikh community had found a home at Nankana Sahib.

Sikh separatism and politics at the gurdwaras

But it was not just the local community that inspired the renovation of these structures. The 1980s witnessed a separatist movement by Sikhs in India. Pakistan, which was still reeling from its defeat to India in the 1971 war, was keen to avenge its “humiliation”. It threw its weight behind the Sikh separatist movement, forming connections with expat supporters in Canada, the US and the United Kingdom. Many of these Sikh leaders travelled to Pakistan, where they began addressing Indian Sikh pilgrims, who would, in small numbers, gather for Guru Nanak’s Gurpurab at Nankana Sahib. Thus, the city’s gurdwaras became places where the neighbouring states played out their politics.

In 1985, at the peak of the separatist movement, Indian diplomats were attacked by a mob of Sikh pilgrims seeking to avenge the killing of thousands of Sikhs in the aftermath of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assassination by her Sikh bodyguards the year before.

![ONLY FOR ESSAY: Guru Nanak and the promise of an inclusive Pakistan [DON'T USE]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/fce2754bb7064c4e92d8c1b8a8b75d4d_18.jpeg)

It was against this backdrop that Pakistan began paying attention to – and money for – the restoration of historically significant gurdwaras. Funding also arrived from the Sikh diaspora, as well as from Pakistani Sikhs who continued their efforts to restore their sacred sites.

While the Sikh separatist movement in Punjab subsided, the relationship between the Pakistani state and Sikh heritage survived. Under the military dictatorship of Pervez Musharraf, who was eager to project his rule as “enlightened moderation”, protection of religious minorities and their festivals acquired a particular significance. Greater numbers of pilgrims from India were given visas, while the state began improving facilities at the gurdwaras.

All subsequent governments have followed; understanding not just the economic benefits of Sikh religious tourism but what it means for the country’s image.

The Kartarpur Sahib corridor

It is this historical background that provides the context for the renovation of Gurdwara Darbar Sahib at Kartarpur, which began in the early 2000s through funds collected by Canadian and American Sikhs, and the opening of the Kartarpur Sahib corridor.

Believed to be one of the holiest Sikh sites in Pakistan, Gurdwara Darbar Sahib, once a modest building in the middle of fields with no proper road leading to it but now a well-served and expansive structure, at Kartarpur Sahib – about 180km (112 miles) from Nankana Sahib – holds the grave and the samadhi (memorial – a small marking constructed over the buried ashes of a deceased after cremation) of Guru Nanak.

Challenging dogma across religions, Guru Nanak attracted Muslims and Hindus as his followers. His philosophical movement argued for an inclusive religiosity that allowed people from different sects, castes and religions to come together and worship one God. After his death, upon the request of his followers, both a grave and a samadhi were constructed for his Muslim and Hindu followers.

The first time I visited Kartarpur in 2013 I witnessed a local Muslim family paying homage to Guru Nanak at his grave. I was told that several local Muslims continued to revere him and were the only devotees who regularly visited the gurdwara after partition, even when the property was taken over by drug addicts and smugglers who, because of its proximity to the Indian border, often stopped there.

I noticed something similar at other gurdwaras associated with Guru Nanak. I visited Gurdwara Sacha Khand – a small single-room, domed building – in Farooqabad, a town about 40km (25 miles) north of Nankana Sahib, a few years ago. The abandoned gurdwara was being used by devotees of a Sufi saint who was buried opposite. While a small shrine had been constructed in its vicinity, the sanctity of the gurdwara had been maintained. The locals were aware of the legends of Guru Nanak and talked about him as they would of any Sufi saint.

At another abandoned gurdwara I visited close to the India-Pakistan border, in a village called Ghavindi, packets of salt and incense sticks, often used in Sufi rituals, had been placed inside, while the floor of the shrine had been recently cleaned.

This tradition was much more obvious when I visited Gurdwara Beri Sahib in Sialkot, a city about 75km (47 miles) northwest of Kartarpur, a few years ago. This year, the gurdwara was reclaimed by the state, renovated and opened for Sikh pilgrims. But before that, it had been looked after by local Muslims, who believed a small grave under a tree in the grounds to be that of a saint.

![ONLY FOR ESSAY: Guru Nanak and the promise of an inclusive Pakistan [DON'T USE]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/40969dd5428e4682bd7d8c566b881c46_6.jpeg)

This appropriation of gurdwaras can be understood as a way of maintaining a site’s sanctity in a way that is religiously acceptable and meaningful to the local community.

But sometimes this religious syncretism is even more direct. The village of Ram Thamman in Kasur district, in Punjab, derives its name from a gurdwara at the centre of the village named after Guru Nanak’s older cousin, a Hindu saint. Starting in the 16th century, it was the site of a festival, Baisakhi, attended by Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus. After partition, the numbers declined significantly, but each April, hundreds of Muslims still gather at the gurdwara to pay homage to Ram Thamman. It is one of the few surviving examples of the kind of religious syncretism that was preached by Guru Nanak and once common across South Asia.

Of course, there are many examples of gurdwaras that are still in ruins – according to a study by Iqbal Qaiser, there are about 70 historical gurdwaras across Pakistan that commemorate some aspect of Guru Nanak’s life, out of which 13 or 14 have been renovated and opened for pilgrims. Some have been desecrated, others gradually incorporated into Sufi shrines, turned into homes or had all physical trace erased. A few have been maintained by local Muslim communities who have inherited through oral tradition some stories from the life of the founder of Sikhism.

But the extensive renovation of Gurdwara Darbar Sahib at Kartarpur and the opening of the visa-free corridor reflects the changing attitudes of Pakistan and the enduring legacy of Guru Nanak and his philosophy. It could address some of the wounds of partition, paving the way for reconciliation between different religious communities, and there is no figure who better personifies that than Guru Nanak, who spent his life trying to bring communities together.

Haroon Khalid is an anthropologist and the author of several books including Walking with Nanak and Imagining Lahore.