Mosul civilians: ‘Who knows who was shooting?’

Thousands in Iraq’s second-largest city have been wounded as the campaign to remove ISIL fighters continues.

Erbil, Iraq – The garden of the emergency hospital in Iraq’s northern city of Erbil is a lush, well-tended oasis full of vivid spring colours. Under the shadow of a tree, the relatives of patients try to rest after the anguished hours of waiting.

“How can I sleep? They are alive by miracle,” said an exhausted Tareq Ahmad as he sat on the grass. A mortar shell seriously injured his son, Rayan, and nephew, Abdallarmeh, leaving them both paralysed from the waist down.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsThe world cannot turn its back on Sudan and its neighbours any longer

Russia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 784

Iraq’s dangerous balancing act between Iran and the US

When the incident happened they were playing football in al-Muthanna, an area of eastern Mosul that the Iraqi government had recaptured from the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, also known as ISIS). Now the boys are lying next to each other in a hospital bed.

Neither will ever walk again.

“The Iraqi army told us to stay and not to leave. I thought it was safe and I told my children to go to play in front of the house,” said Ahmad. “I was in the army in 2003 and I know how the army works. If a place is not safe, I would tell people to ‘be careful, don’t go out’. This is our life – am I wrong? Who will give them their lives back? They had to tell us that it was not safe,” the father repeated as he covered his tearful eyes with his hands.

READ MORE: Mosul’s civilian deaths – How the US destroyed Iraq

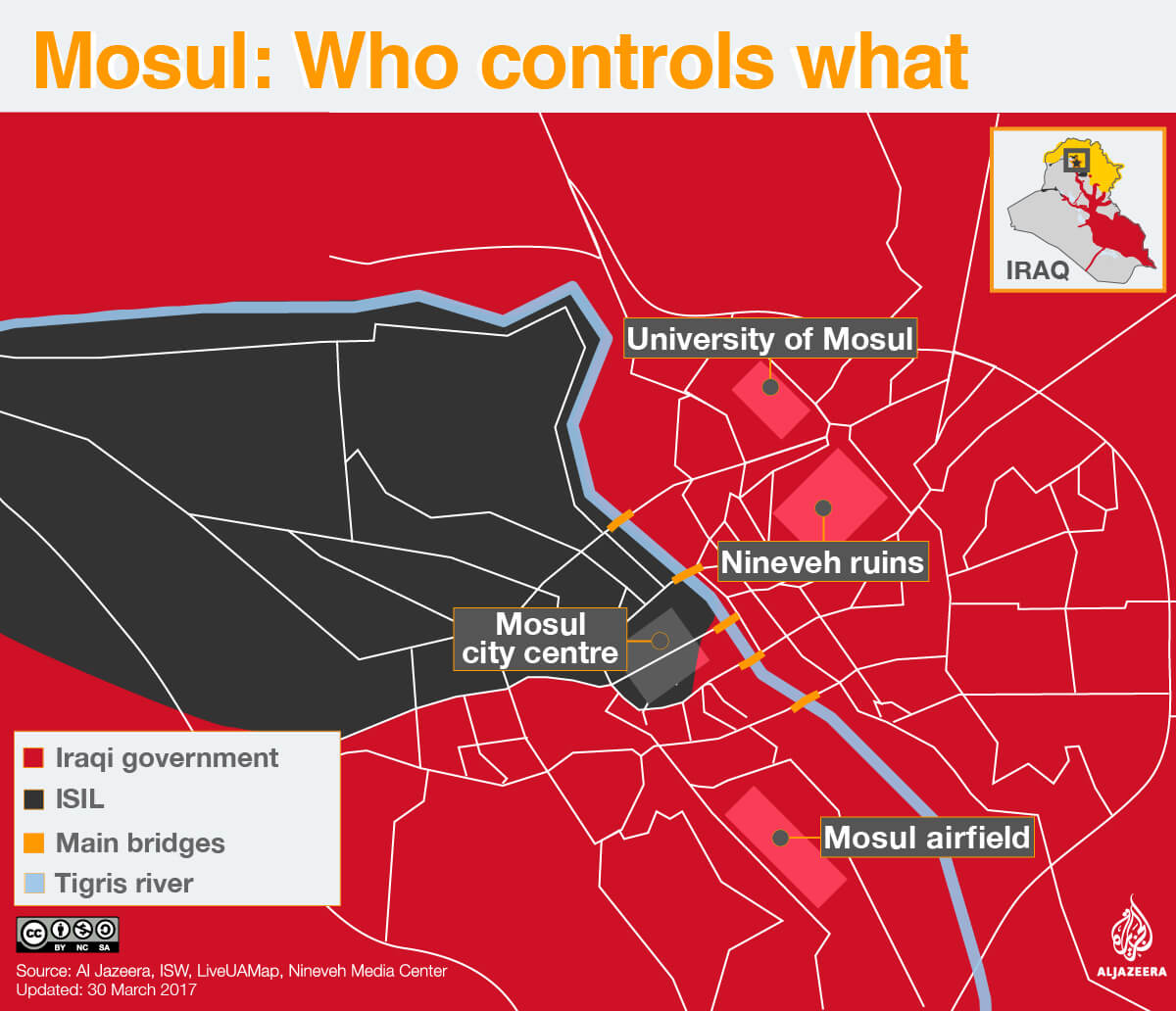

Mosul, Iraq’s second-most populous city, fell to an ISIL blitzkrieg in June 2014. The group’s fighters poured over the border from Syria, seizing large swaths of northern Iraq. Two years later, the Iraqi army – backed by local militias, Kurdish forces and air strikes carried out by an international coalition – began an operation to drive ISIL out of the city.

The Iraqi army told us to stay and not to leave. I thought it was safe, and I told my children to go to play in front of the house. Who will give them their lives back? They had to tell us that it was not safe.

Because hundreds of thousands of civilians are trapped in Mosul, anti-ISIL forces have had to limit their use of aerial attacks and artillery in the city. Nevertheless, hundreds of civilians have been killed by coalition air strikes and shelling, as well as in the counter-attacks launched by ISIL.

Inside the hospital, most of the victims – half of whom are women and children – were wounded due to the fighting in Mosul. “Who knows who was shooting? We were in the middle of the fighting and we couldn’t go out for six days,” said Chad, a 19-year-old woman whose leg was injured in a mortar strike in Mosul’s Wadi Hajjar district.

“There was a sniper on the rooftop of our house and then a mortar hit us. I lost my brother. I don’t remember much,” she told Al Jazeera as she waited to undergo an operation on her leg.

For those like Chad, the lines separating the “good guys” from the “bad guys” are fading away. The human cost of the campaign to take Mosul has increased since Iraqi forces advised civilians to stay in their homes. The reason: the Iraqi military wants to limit the amount of human displacement as it tries to push ISIL out of the city. Despite its calls, though, 200,000 people have fled since the start of the operation to retake the western half of Mosul. With government forces bogged down in vicious street-to-street fighting, ISIL has sought to exploit the strategy of “civilian protection”.

“Civilians are being manipulated [by ISIL] to slow down the military operation,” said Michela Paschetto, a nurse and medical coordinator for Emergency, an Italian NGO that runs the Erbil hospital. “Families are being taken by ISIL to fill the buildings where [their units] are hiding and they use them as human shields.”

Sabrina’s house in western Mosul was hit by a mortar fired by ISIL, killing her husband and two children and wounding her. “I stayed at home for weeks with my mother, who took care of my wound. I could not run away because there were [ISIL units], but the Iraqi army told us to stay in the house and I lost my family.”

Since October 2016, when the Mosul campaign began, more than 6,000 wounded – over half of them civilians – have been sent to hospitals in Erbil and liberated eastern Mosul, as well as to field hospitals around the city.

In February and March alone, Emergency’s hospital treated more than 500 civilians coming from field hospitals, where medical teams work to stabilise patients before they are transferred to better-equipped hospitals nearby.

Inside the emergency room, another father is trying to alleviate his daughter’s pain. “We are the victims of this war. Look with your eyes: Is she an infidel? She is only a girl,” said Abu Shams Ali, as he stroked his daughter’s forehead and wiped away her feverish sweat.

A mortar strike wounded Lina in her abdomen two weeks ago in western Mosul’s al-Jadida neighbourhood.

“Our house was close to the front line and ISIL forced us to move inside another house. As soon as we got inside, I heard a loud explosion near me,” said 14-year-old Lina as she laid in the hospital, her face pale due to an infection. “ISIL treated us harshly. We were forced to wear the full-length hijab; men couldn’t smoke or wear trousers,” she recalled.

Like Lina, most of the patients treated at the Emergency hospital were wounded by shells and bullets. The doctors call these “dirty wounds”.

“All the wounds of war are dirty by definition,” said Marco Pegoraro, Emergency’s surgeon. “This is because all the shell fragments, everything on the ground – stones, metal – is projected inside the body. But they are also dirty because the first victims of wars are civilians caught between the fire [from both sides].”

|

|

Due to the difficulty in escaping from areas where heavy fighting is taking place, thousands of wounded civilians have been unable to access timely medical care – leading to an increase in the number of amputated limbs. One of these is Gazban, who waited hours before an ambulance was able to reach him.

“I said, ‘please do not cut my legs’, and then they anaesthetised me. And when I woke up, my legs were gone,” said Gazban, 19, as he sat in a wheelchair at the entrance of the hospital.

Sitting close by was his mother, Amira, who recalled the day of the incident in detail. “On February 26, at 9 o’clock, my son was in front of the door and a mortar hit our house. I heard the explosion and I ran outside. I saw my son bleeding and without legs. I tried to unite the bones and the parts of his legs,” she said.

Most of the relatives and patients interviewed said that although they were grateful that the Iraqi army had come to retake Mosul, they do not want revenge. Instead, they all said that they simply want to return to a peaceful, normal life.

“I would like to start school again, go to college and continue my life,” said Gazban. “Even if it will not be the same anymore.”