Nauru: A place of abuse and desperation

A former Nauru refugee prison camp employee describes a process of dehumanisation and a resulting mental health crisis.

Following recent revelations, giving further details of conditions for asylum seekers in Australia’s offshore detention network, a former refugee prison camp employee, Natasha Blucher, has told Al Jazeera of her relief at seeing the publication of documents leaked from within the system, reporting on alleged human rights abuses against some 442 people who remain on Nauru as asylum seekers.

“It was somewhat vindicating because now there’s a body of evidence from Nauru,” Blucher, a former social worker on Nauru, said of the document leak in an interview from Darwin, in Australia’s north.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUN report charts lethal cost of migration over past decade

Conflict, climate, corruption drive Southeast Asia people trafficking: UN

Bodies of three Rohingya found as Indonesia ends rescue for capsized boat

On August 10, the Guardian Australia news website published a catalogue of more than 2,000 internal incident reports, some of which detailed instances of sexual abuse of women and children, sexual harassment and violence inside the Nauru prison camp facility.

Even prior to the leaks, there have been calls from NGOs to investigate the allegations against Nauru regarding the living condition in which the asylum seekers are kept. Tuesday, two members of a group of Danish diplomats, concerned over the reports and bound for the infamous island, were denied entry visas by the Nauru government.

The reports cite a security guard reaching into a child’s pants, acts of violence and threats by camp guards directed at children, and a woman’s request for longer shower times being granted by a camp guard on condition of sexual favours.

Blucher said that all staff working at the refugee prison camp on Nauru were immediately trained to complete incident reports like those featured in the leaked documents. Filing them formed a major part of the workload – some days requiring the completion of up to 20 incident reports.

“It was quite an onerous reporting system, but we knew it meant we were creating a paper trail,” Blucher said. “It was intensive because there were so many incidents happening.”

READ MORE – Nauru: Leak reveals children sexually abused at prison

Process of dehumanisation

Aside from major incidents, the leaked documents offer an insight into the banal aspects of life within the Nauru prison camp – arguments and fights among asylum seekers, arguments between detainees and camp staff, and complaints about camp conditions.

Such instances are a symptom and part of the cause of what Blucher describes as a dramatic mental health crisis inside the camp resulting in regular instances of self-harm.

“The mental health deterioration of people on Nauru was rapid and violent,” she recalled. “People weren’t violent against others but very violent against themselves. It was loud, messy and horrifying.”

In October 2014, Blucher was among nine employees of the non-profit organisation Save the Children who were removed from Nauru after allegations that they had encouraged asylum seekers to self-harm and protest against life in the prison camp.

|

|

The group was subsequently cleared of any wrongdoing by two independent reviews.

The offshore detention of asylum seekers arriving in Australian waters by boat recommenced in 2013 with the opening of camps on the tiny Pacific island nation of Nauru and Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island.

Since then, legislation and measures have been implemented to prevent access to journalists and to discourage people working at the detention system from speaking out about conditions inside the camps. Blucher feels such secrecy exacerbates the mental health problems found on Nauru.

“Dark aspects of human nature emerge in these environments because people can act with complete impunity,” she reflected.

“There is a weird dichotomy in the relationships between the security officers and asylum seekers. Officers start by enforcing the rules they’ve been instructed to follow, but nobody likes being locked up with rules enforced on them,” Blucher said.

A self-perpetuating cycle of abuse emerges in these circumstances, Blucher explained. “Asylum seekers react negatively and start being rude to the officers. The officers think they’re rude people so become crueller and begin enforcing the rules in ways that aren’t predictable. Asylum seekers get frustrated and act out, thinking the guards are awful people, making the guards nastier again. In the end, the two groups start despising each other until the officers stop seeing the asylum seekers as positive human beings.”

In such a manner, asylum seekers become dehumanised in the eyes of camp security guards, who refer to detainees by numbers rather than names, Blucher said.

“If you don’t give a person a name, how do you treat them like a person?” she asked. “Something asylum seekers would frequently say is that they were being treated like animals. They would ask me if they were human. People would be genuinely confused and ask you to tell them they’re not an animal. I would try to tell them to forget the numbers given to them.”

![According to Blucher, asylum seekers had become dehumanised in the eyes of camp security guards, who would refer to detainees by numbers rather than names [Luis Ascui/Getty]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/8c64b47ada0f46aaa18e620914c63526_18.jpeg)

Depression and trauma

Almost all camp residents suffered from depression, Blucher said.

“The thing I found most shocking – it struck me when I first arrived, and it struck me again when I realised it wasn’t affecting me any more – was people sitting or lying in the corridors outside their tents or in areas around the camp just staring at nothing; completely listlessly.

“It became normal and you would only notice when someone began screaming and collapsing on the ground or beating their head against a fence.”

Blucher’s employment on Nauru, from July to October 2014, covered a period of frequent protests and acts of self-harm among asylum seekers.

“At one point three teenage boys and four men stitched their lips together and sat outside the mess [hall],” she said.

“Everybody, including families with children, had to walk past them to get into the mess to eat. All the kids were looking at them. After someone stitches their lips closed, it swells up and becomes [infected with pus]. It’s really awful to look at, and I think it really affected the children.”

Describing conditions on Nauru as a “powder keg”, Blucher attributes the spate of self-harm incidents, which has included one death from self-immolation, to the intentionally punitive nature of Australia’s detention system.

“While these camps are miserable, they are no more miserable than other refugee camps around the world,” she said. “Nauru is a hard place to live but I haven’t heard of the horrific mental health deterioration that I have witnessed in Nauru elsewhere, and I think it’s because everybody knows it’s intentional.

“The people in those camps know that Australia could provide them with decent care and support and living standards, and they’re intentionally not doing that. People are stuck and being intentionally kept there in a miserable, horrific state. It breaks people.”

Working a rotating roster of three weeks at Nauru and three weeks on leave back in Australia, Blucher noticed herself becoming increasingly distant from friends and family on return trips home.

“The first break back, I was all right. Then I found it hard to talk to people,” she remembered.

“It was like, you’d seen something horrific and you come home and everybody is trying to act normal – but you can’t. I would become frustrated and have to stay away from people. You can’t communicate with people because they’re not going to understand.”

Following her dismissal, Blucher’s doctor informed her that she had the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. After a period of rest, she now works for the Darwin Asylum Seeker and Support Network, an advocacy group assisting refugees and advocating for policy changes from the Australian government.

READ MORE – Australia deliberately ignores refugee abuse: report

Government response

The Australian government continues to play down the importance of reports emerging from Nauru.

“Many of the incident reports reflect unconfirmed allegations or uncorroborated statements and claims – they are not statements of proven fact,” an official Department of Immigration statement said.

When contacted for comment, the Department of Immigration referred Al Jazeera to this official statement.

![Many fear that as the Australian government continues to ignore the reports of human rights abuses coming out of Nauru, conditions at the camp will become worse [Mick Tsikas/EPA]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/3c1af308a6154f88a17b9596041ca5ba_18.jpeg)

Immigration Minister Peter Dutton went further, inferring complaints of sexual harassment or acts of self-harm were often done in order to gain entry to Australia.

“I have been made aware of some incidents that have reported false allegations of sexual assault because, in the end, people have paid money to people smugglers and they want to come to our country,” Dutton told Australian radio. “Some people have even gone to the extent of self-harming, and people have self-immolated in an effort to get to Australia.”

“The government’s response has always been absurd in relation to this, and it’s really not surprising that’s how they’re responding now,” Blucher reflected. “It’s incredibly frustrating.”

The arrival of asylum seekers has been a highly charged political issue in Australia for more than a decade, and Blucher said she hopes that attitudes will change.

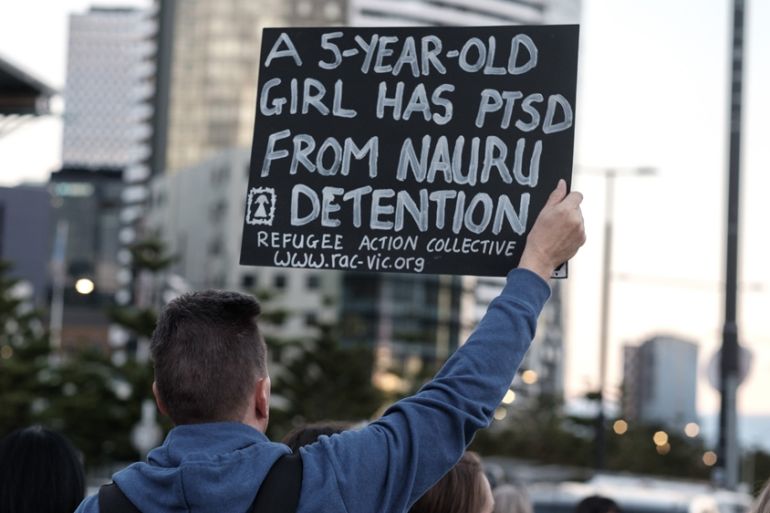

“There are times when public opinion shifts, but what I’ve learned is you often have to pitch information to the public in a way that is emotional and not technical,” she explained. “If you talk about human rights abuses people seem to shut down, but if you show them a picture of a baby or a family the response is different.”

New tactics to alter negative opinions are necessary, according to Blucher. One successful campaign she worked on involved a child whose mother wished that her son might one day be free to own a puppy.

“Their story contained so much harm and suffering, but instead we focused on this and it got a response in the Australian community. It’s hard for us to do because we know everything is so serious, but we have to try to focus on things people can accept, acknowledge and feel.”