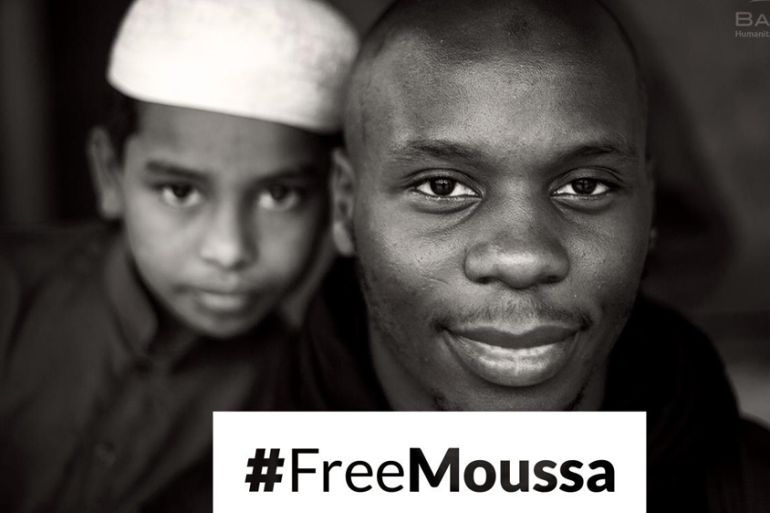

The case of a French aid worker arrested in Bangladesh

French Muslim Moussa Tchantchiung says he was in the country to help Rohingya refugees there when he was arrested.

The French government, human rights organisations and social media users worldwide have spent the past two weeks calling on the Bangladeshi government to release Moussa Tchantchiung, who was arrested on December 22.

Tchantchiung is a French citizen and a member of the French NGO Barakacity, a human rights organisation providing humanitarian services to needy communities in 22 countries. He was arrested by the BGB, an elite Bangladeshi police unit while on his way to visit Rohingya refugee camps in the country. The Bangladeshi government has since accused him, among other charges, of having ties to “terrorism”.

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘Mama we’re dying’: Only able to hear her kids in Gaza in their final days

Europe pledges to boost aid to Sudan on unwelcome war anniversary

Birth, death, escape: Three women’s struggle through Sudan’s war

The #FreeMoussa campaign, which has been trending on Twitter, was started in reaction to his arrest, while online petitions have called on the Bangladeshi government to release him. Celebrities and intellectuals have been publicly drawing attention to the case.

Barakacity insists that Tchantchiung had merely travelled to Bangladesh to provide humanitarian assistance to the Rohingya population, which has been living in camps in the south of the country that the Bangladeshi government considers illegal.

The Rohingya established the makeshift camps, 50km from the border with Myanmar, in an area surrounded by Bangladeshi military checkpoints that allegedly prevent them from moving further into the country to seek refuge.

Amnesty International considers the Rohingya, an ethnic, linguistic and religious minority from Myanmar, to be the “most persecuted refugees in the world“.

Barakacity says that Tchantchiung had been visiting Rohingya schools and was then stopped at a checkpoint while on his way to the camps in the south.

He has since been held in conditions described as “catastrophic” by his supporters following audio statements recorded by Tchantchiung and released via social media. In the clips, Tchantchiung explains how he has been moved between a tiny prison cell shared with more than 40 other – mostly Rohingya – prisoners – and a solitary confinement cell in the Central Prison in Cox’s Bazar in southern Bangladesh.

He is still waiting to hear what his official charge will be and whether he will be forced to spend 10 years in prison if found guilty of having “links with terrorism”.

Speaking to Al Jazeera on the condition of anonymity, a representative from the Bangladeshi embassy in France said that “Moussa is in safe custody, in good health and has access to French officials who have already met with him”.

“The issue is that he was found near the border [with Myanmar], which worries the officers working there because extremism and terrorism cross over into Bangladesh from there.”

“In Bangladesh, humanitarians can work freely anywhere but in the border area [where most of the Rohingya are forced to remain],” the representative continued, describing it as “a sensitive area”.

On the subject of why Tchantchiung’s arraignment has been repeatedly postponed, including most recently on Thursday, the representative told Al Jazeera that legal procedures in Bangladesh take time, “so you just have to wait”.

![The issue has sparked a #FreeMoussa campaignand online petitioning calling on the Bangladeshi government to release Moussa Tchantchiung [Photo courtesy of Barakacity]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/6302a523cc114714b85f4a06134540b7_18.jpeg)

The French government, meanwhile, has been criticised by activists and observers who believe that it has not done enough to help Tchantchiung. The director of Barakacity even accused the government of double standards, suggesting to Al Jazeera that the government would have done more for a French citizen who was not Muslim.

But Romain Nadal, the spokesman for France’s ministry of foreign affairs, told Al Jazeera that the French government has been in contact with Tchantchiung, his family and Barakacity, and has looked into the conditions of Tchantchiung’s imprisonment.

“Like every other French detainee in the world, [Tchantchiung] has received French consular protection,” said Nadal.

Tchantchiung ‘s supporters have also been concerned with sections of the French press, which have portrayed Barakacity as an organisation that is “too religious” and involved in “suspicious activities“.

Francis Chouat, the mayor of the Evry suburb of Paris, where Barakacity is located, accused the NGO of having links to “terrorism” and said that humanitarian assistance should not be provided on the basis of Islamic principles.

My objective was for the Rohingya to be recognised

Barakacity maintains that there is no evidence to support the claims that it is anything other than a humanitarian organisation, and that it has provided sufficient proof of its work with the Rohingya.

Tchantchiung, has released some statements since his arrest, sayng: “My objective was for the Rohingya to be recognised.” He added that he hopes his imprisonment and the campaign for his release has at least achieved that.

Al Jazeera spoke with Idriss Sihamedi, the director of Barakacity in Paris, about Tchantchiung’s case, the plight of the Rohingya in Bangladesh, and the work of the NGO there.

Al Jazeera: What are the latest developments in Moussa Tchantchiung’s case?

Idriss Sihamedi: During the last hearing [on January 5], the judge decided that taking any further decision would have to wait until more inquiries were done.

Moussa had seven lawyers present – five Bangladeshi and two French. This surprised the court, as they are not used to the presence of foreign lawyers and international campaigns.

Our lawyers arrived yesterday [on January 6] and were stuck at the border for a very long time. When they finally met the prosecutor, he asked them three questions: Did Moussa want to visit the Rohingya? Was he working with an NGO? What was he doing at that place where he was caught?

The lawyers are saying that, given the questions, this case has clearly come about because Moussa was in touch with the Rohingya, and they are trying to hide it by saying different things. They say he had the attitude of a ‘suspect’, even though he was walking toward the camps but he had not yet even crossed the red line into the illegal camps.

They also accused him of possibly trafficking organs, and of being linked to terrorist activities. And then they accused him of falsifying papers as well.

They based everything on [an article in] the Bangladeshi constitution, which allows them to persecute him due to his supposedly exhibiting “suspicious behaviour or activities”.

Al Jazeera: Did Moussa go on the mission officially for Barakacity?

Sihamedi: Yes, he did. But we didn’t officially seek permission from the Bangladeshi government because we were going to see the Rohingya who are being held in illegal camps – and the government has already made it clear it will not let anyone to do so. We had already gone there six or seven times before, however, without any issues.

The Rohingya are living in illegal camps there, where the humanitarian conditions are catastrophic. It is getting more and more difficult, especially since 2009, when Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina was elected. She doesn’t want any humanitarian organisation to go anywhere near the Rohingya.

Their condition is so awful, it is even worse than in Myanmar. She doesn’t want them to be officially recognised, and her platform since she came into power has been “Why should they be Bangladesh’s problem?“

Moussa, with Barakacity, was going to conduct some audits – to document their condition, their numbers, cases of rape and other major human rights violations being committed against them, and so on.

And Barakacity is not the only organisation that has had issues when dealing with the Rohingya. There is another organisation called Global Rohingya Centre, which has had issues with the Bangladeshi government as well.

I think about three human rights workers went to prison there for their work. The government has made it a point to prevent people from accessing the persecuted Rohingya.

Al Jazeera: Have you been in touch with the Bangladeshi government?

Sihamedi: We’ve only been in touch with the Bangladeshi embassy in France …. We’ve only been able to get information from our own people on the ground there, as opposed to any official government voice.

Al Jazeera: What about the French government?

Sihamedi: We contacted the Quai d’Orsay [the French foreign ministry] and the French embassy in Bangladesh, but we have yet to officially receive any information from them.

What’s crazy is, we have someone like Serge Atlaoui in Indonesia who was linked to drug trafficking, and the whole French government stood up and questioned the sovereignty of Indonesia to carry out a death sentence against one of France’s own citizens.

And yet, with Moussa, a human rights worker who went to Bangladesh for a just cause, the French government has yet to do anything.

Al Jazeera: The spokesman of the French foreign ministry tweeted saying that the consul went to visit Tchantchiung in prison. How did the meeting go?

Sihamedi: It was actually pretty awful.

The consul told us he spent more than an hour and a half talking to Moussa and that it was a productive meeting. However, when we were able to get in touch with Moussa he told us the meeting went very bad and didn’t even last 20 minutes. Moussa said the consul was very condescending and he felt judged … for going on a mission to help the Rohingya.

So yes, officially, they say they are doing something but in reality it is not exactly true.

[When Al Jazeera put Sihamedi’s claim about the meeting to Romain Nadal, the spokesman for France’s ministry of foreign affairs, he said that the French consular officer in Bangladesh had a very long and productive meeting with Tchantchiung and that he was “extremely surprised” to hear otherwise.]

Al Jazeera: Recently, the mayor of Evry said that working to help free Tchantchiung should not be mistaken with helping an organisation [Barakacity] that supposedly has links to “terrorism”. The media has portrayed your organisation in a similar light. What is your response to these accusations?

Sihamedi: Barakacity’s media backlash is just a reflection of the present French political climate. Suspicion, fear, Islamophobia – this is what we are dealing with on a regular basis now.

However, ordinary citizens are, thankfully, not intimidated by the government’s game. Barakacity is a very successful NGO, fully supported and funded by private donors. It is operating in 22 countries, doing work that many organisations aren’t doing.

Saying that we are solely a Muslim or an Islamic organisation isn’t the right way necessarily to describe us. We work with Muslims as well as non-Muslims.

For example, in the Central African Republic we did a lot of work with Christian women who unfortunately suffered from human rights abuses like rape. Lots of our work is not being done by any other organisation.

We are basically causing an inconvenience to the government because we are very active and independent.

Al Jazeera: What are the possible outcomes in Moussa’s case?

Sihamedi: We’re remaining positive with regards to Moussa’s case now. But even if Moussa does go to prison, this doesn’t mean that Barakacity will stop sending people to visit and work with the Rohingya.

We are a humanitarian organisation and we defend human rights. If we have to go to prison to defend the rights of the Rohingya then we are ready.