How comic books helped fuel Japan’s love for the atom

Characters such as Astro Boy extolled benefits of nuclear energy, exacerbating the shock when disaster struck in 2011.

If you were looking for a historical document that encapsulated 1970s Japan’s position on nuclear power, you could trawl through policy papers, scholarly articles or news archives.

Or you could travel to a manga store in western Tokyo, and pick up a couple of vintage comic books: “Atom Goes to the Jungle,” and “The Jungle Sings Again.”

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsInside the pressures facing Quebec’s billion-dollar maple syrup industry

‘Accepted in both [worlds]’: Indonesia’s Chinese Muslims prepare for Eid

Photos: Mexico, US, Canada mesmerised by rare total solar eclipse

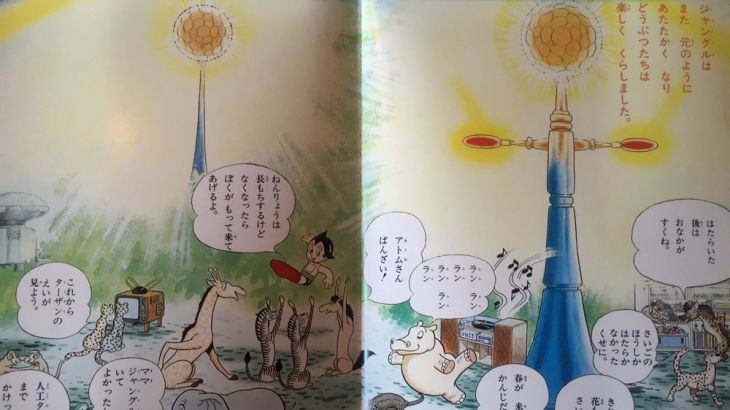

They feature the Mighty Atom, or as he’s better known outside Japan, Astro Boy, and they are quite extraordinary – beautifully drawn and bitterly ironic.

The first story goes something like this:

In a far off jungle, the animals are worried. Mother nature has forsaken them: Their climate is getting colder, the plants are dying and they’re getting hungry.

So they call on Astro Boy for help. There follows an earnest discussion about how they can’t heat their habitat with hydropower, because the water’s frozen. Oil is running out. What they need is a nuclear power station.

Astro Boy flies a reactor from Japan to the jungle, and they all pitch in to build a power station around it.

Even the hyena decides to help. A tiny mouse struggles to keep the blueprints unfurled. All together for the common good: nuclear energy.

In no time they’ve built a gleaming, safe solution to their climate problem – and go a step further, using it to power an artificial sun that helps the plants grow again and gives them a healthy bit of Vitamin D on the side.

Astro Boy’s creator, Osamu Tezuka, always insisted he’d never intended to make a poster child for Japan’s nuclear industry, and that he’d had nothing to do with the jungle stories.

Nonetheless, they were handed out as free pamphlets during school visits to power plants – the message conveyed through kawaii (cute) little critters: Nuclear power is safe.

In the “Jungle Sings Again” that message is doubted, then triumphantly proved true.

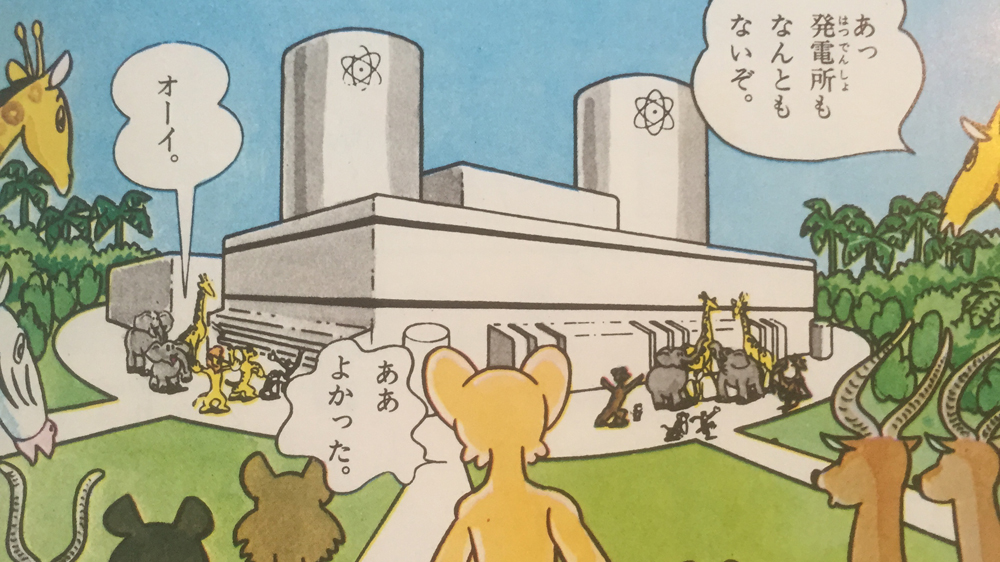

Another group of animals suffering in similar circumstances comes to Japan to study at a nuclear university.

They graduate, celebrate, then go home to build their power station.

Astro Boy tells them it’s so safe it could even survive an earthquake.

An earthquake duly happens, causing a tsunami for good measure. The animals that run away are terrified as the ground shakes and the trees topple.

They return to find the heroic lion, who stayed at the plant, welcoming them back in front of an entirely unscathed reactor. The animals agree that Astro Boy had been right all along, and they sing their thanks.

It hardly needs saying that in the real world Japan’s nuclear technology was far from the pristine perfection of the books.

When the earthquake and tsunami struck Fukushima Daichi in 2011, reactor buildings exploded, cores melted and the world was faced with its worst civilian nuclear disaster since Chernobyl.

The industry that had been churning out these cheery stories was in fact complacent and poorly regulated.

The Astro Boy stories might be on the heavy-handed end of the spectrum, but they reflect how consistently Japan’s public was told across the decades to stop worrying and love the atom.

It began in 1956, with the Atoms for Peace exhibition in Hiroshima, just 11 years after the city was obliterated by a nuclear bomb, and continued until Japan had more than 50 nuclear reactors.

They all gradually shut down in the wake of Fukushima. The first restart, at the Sendai nuclear power station, is due to take place within the next two days.

On Saturday, Japan’s nuclear watchdog, the Nuclear Regulation Authority, said a repeat of an accident on the scale of Fukushima would not be possible under its new procedures.

But it added there was no such thing as absolute safety.