Despite animosity, Moscow’s Muslims change the city

At least 1.5 million Muslims in Russia’s capital form the fastest growing and most ethnically diverse demographic group.

Moscow, Russia – Surrounded by movable metal fences and police, they placed their prayer rugs and shreds of wallpaper on the cold asphalt along the tram tracks.

Then they planted their feet and exhaled “God is great!” They bent, knelt, and prostrated in front of the golden-domed Sobornaya mosque despite the bewildered and scared faces of passersby and baton-wielding police officers around them.

More than 60,000 Muslims gathered at the square and five temporarily blocked streets around Moscow’s main mosque, with an additional 180,000 gathering at five other mosques and three dozen temporary sites in Moscow and the greater Moscow region, to mark the end of this year’s holy month of Ramadan, police said.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsEurope pledges to boost aid to Sudan on unwelcome war anniversary

Birth, death, escape: Three women’s struggle through Sudan’s war

Does Israel twist humanitarian law to justify Gaza carnage?

Each person had to pass through a metal detector and undergo an identification check.

Some Muslims were indignant about the treatment they faced on one of the year’s holiest days.

“You want to pray at a mosque, you have to enter a cage,” Murad Abdullaev, a full-bearded 29-year-old from Derbent, Russia’s southernmost city in the restive province of Dagestan, told Al Jazeera.

“You pray at work, you get reprimanded, but when your colleagues show up hungover or take long cigarette breaks, it’s OK,” he said describing his colleagues at a construction company in southern Moscow.

Moscow is slowly adapting to being Europe's largest Muslim city, and Muslims are gradually adapting to it.

Some Muscovites are also unhappy about the inconveniences they face during the celebration of the two major Muslim religious holidays Eid al-Fitr – the breaking of the fast festival at the end of Ramadan, and Eid al-Adha – the festival of sacrifice.

“Again, [some] streets are full of praying people, again the adjoining streets are blocked, [there are] tensions with police,” popular blogger Ilya Varlamov wrote.

“For many years, this has been the picture in Moscow twice a year. And each time, everyone is surprised,” the blogger said.

On days like these, Moscow seems quite a hostile place for the Muslims that now live here and form the fastest growing and most ethnically diverse sector of the population.

With an official population of 12.5 million, Russia’s capital is now home to at least 1.5 million Muslims, according to political analyst Alexei Malashenko. This is by far more than the Muslim population of any other European city where the local population is not predominantly Muslim.

“Moscow is slowly adapting to being Europe’s largest Muslim city, and Muslims are gradually adapting to it,” Malashenko told Al Jazeera.

RELATED: Chechnya, Russia and 20 years of conflict

Moscow’s Muslims

Russia’s identity was forged during centuries-long confrontation, coexistence and cooperation with Muslim neighbours. The tiny principality of Moscow slowly defeated the Golden Horde, a powerful Mongol-Tatar khanate, and then waged countless wars in and against Ottoman Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and the Caucasus.

The Muslims who now live in Moscow are mostly the descendants of this historical legacy. Ethnic Tatars, Russia’s third largest ethnic group after Slavic Russians and Ukrainians, have lived here for centuries; Azeris settled here in the 1990s after fleeing the Armenian-Azeri war.

They were followed by an ever-growing number of natives of Russia’s Caucasus – a multiethnic and heavily subsidised region plagued by insurgency and violence.

Since the early 2000s, millions of labour migrants from ex-Soviet Central Asia have flooded into Russia, mostly seeking low-paid labour jobs. There is also a visible presence of Muslims from sub-Saharan Africa, the Indian subcontinent, and the Middle East.

Yet, whether Russian-born or immigrant, secular or practising, Muslims don’t feel welcome here. This is partly due to the fact that many Russians feel threatened by this influx of Muslims. The attacks carried out by Chechen fighters and female suicide bombers since the early 2000s also still frighten many.

RELATED: Chechnya: War Without Trace

Although there are no separate polls available for Moscow, a 2013 survey by VTsIOM, a state-owned pollster has found that almost one in seven Russians don’t want to have Muslim neighbours, one-fourth do not want to live near a Caucasus native, and 28 percent don’t want Central Asians next door. Some 45 percent of Russians support the nationalist slogan of “Russia for ethnic Russians”, the poll found.

Making inroads

Moscow has only six mosques, and attempts to build new ones are met with protests and rallies.

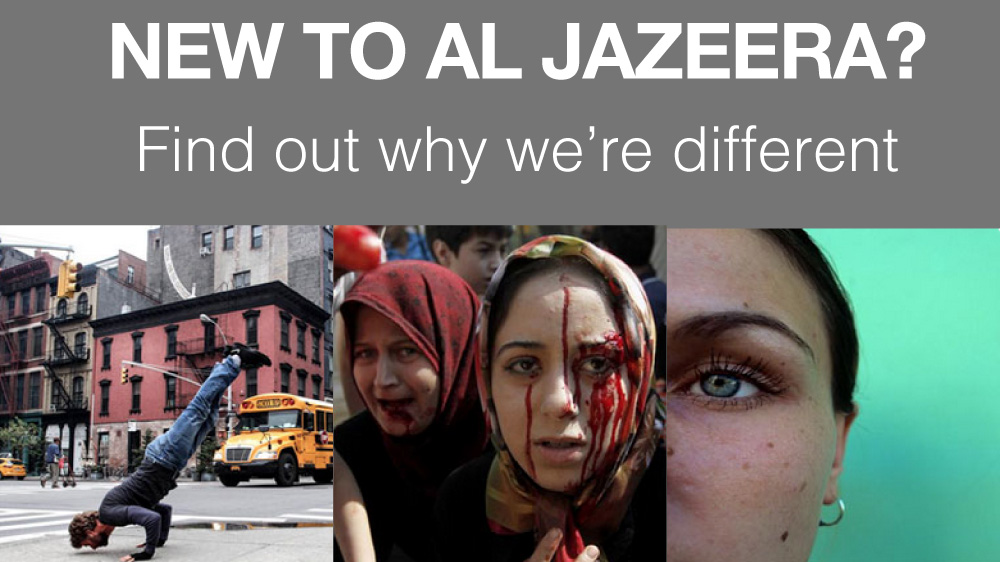

Women wearing hijabs walk next to ladies who wear mini-skirts and provocative clothing even in sub-zero winter temperatures. Police routinely stop Muslim men for document checks based on their appearance – their skin colour, beards and clothing.

![Many shops have opened that cater to Russian Muslim clients [Alexander Zemlianichenko/AP]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/04969b58a7ee4c639bfb55bfbfc849e8_18.jpeg)

There are only two halal hotels in the city that sees millions of visitors a year. The city’s only Muslim gym and health clinic closed down shortly after opening.

There are only a handful of Muslim kindergartens or schools. “They are far to get to and there are too few of them,” Jannat Babakhanova of Limpopo, a small network of Muslim kindergartens, told Al Jazeera.

However, countless bakeries, cafes and restaurants have sprouted throughout Moscow selling Central Asian flat bread and samosas, pilaf and kebabs.

Halal food has become a profitable business – and many non-Muslims frightened by the low quality of foodstuff produced in Russia, have switched to halal meat.

“The market was untouched, and it was easy to fill it,” Venera Kaderova of Halal Ash, a small producer of halal meat products, told Al Jazeera about the company’s launch in the early 2000s.

“These days, the market is competitive,” Kaderova said.

But the profitability of halal foods also triggered production of knock-off halal – and the emergence of such oddities as “halal” eggs, mineral water, and even snacks to go with beer.

The presence of Muslims in Moscow prompted another trend – the growing number of ethnic Russians who convert to Islam.

Anastasiya Korchagina changed her first name to Aisha after converting to Islam almost five years ago and now wears a vivid headscarf and conservative attire.

“I hear many compliments about how I am dressed and how beautiful it looks,” Korchagina told Al Jazeera. “I’ve never faced bad attitude. It’s just not there.”