Counterfeit euros: Fake it ’til you make it

A small Italian city near Naples is renowned for producing ‘the best fake euros in the world’.

Milan, Italy – In Italian, the word arrangiarsi refers to the art of cutting corners and being adaptable in order to overcome obstacles.

In the spirit of arrangiarsi, some people in the Naples area have found their own way to get rich quick: counterfeiting euros and selling the currency on the black market.

The most renowned place for this lucrative art is Giuliano, a small city just north of Naples that in recent years has been dubbed “Europe’s counterfeit capital”, and become renowned in the criminal world for producing “the best fake euros in the world”.

According to information provided to Al Jazeera by the Carabinieri, Italy’s military police, about 90 percent of the fake euros in circulation around the world originate in the Naples area, and are produced by people affiliated with a loose criminal organisation referred to as the “Napoli Group” by Europol, the law enforcement agency of the European Union, and Interpol, a non-governmental organisation facilitating international police cooperation.

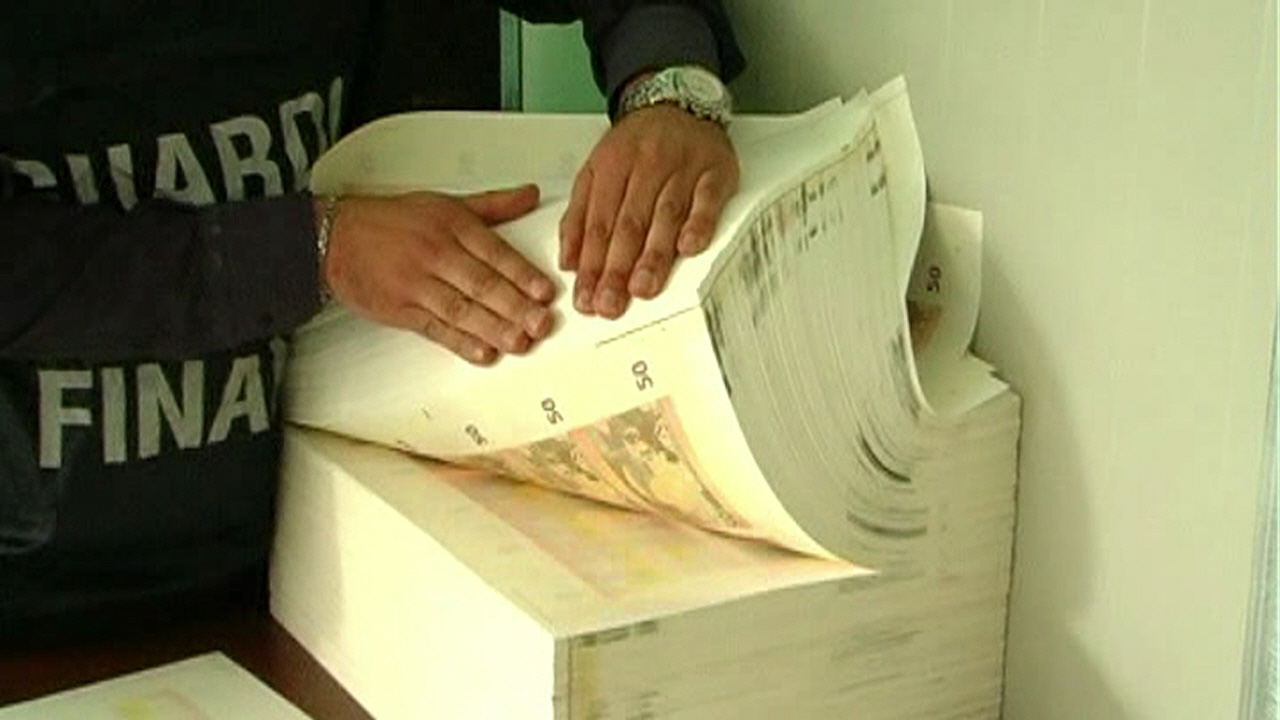

|

| Italian police examine counterfeit euros [Alberto Mucci] |

The reputation of the Napoli Group is so widespread that aspiring scam artists from across the globe are heading to Giuliano to learn from the print-makers – the best of the best.

Funny money

According to data obtained by the European Central Bank (ECB), over the past three years the circulation of fake euros has grown from 296,000 in 2011 to 331,000 in 2014, roughly a 10 percent increase in volume.

The 20 and 50-euro notes are the most commonly counterfeited, making up 81.2 percent of fake bills, followed by the 100-euro notes at 10.1 percent.

Reached for comment by Al Jazeera, Alessandro Langella, the head of the operational team of Naples’ Guardia di Finanza – a police force that deals with financial crimes – explained that “the real number of circulating fakes is probably larger than the official one, as it is impossible to determine the exact quantity in the economy”.

On the other, Naples has historically been a hub for publishing houses, an industry that created an ecosystem of skilled printers who, when the local economy started to decline, were more than happy to reinvent themselves in the counterfeit business.”

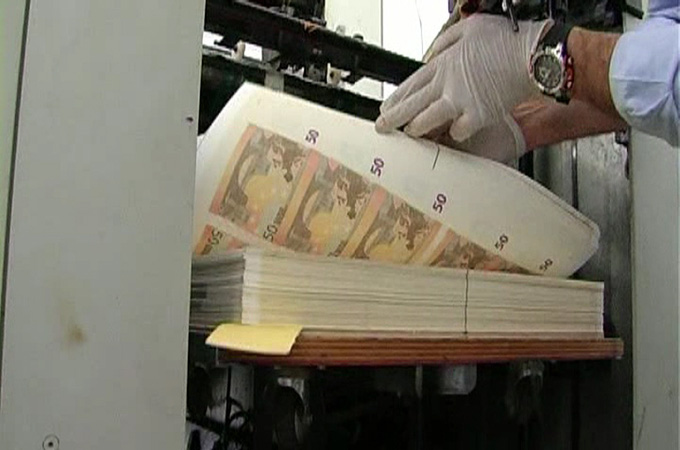

|

| Italian police examine counterfeit euros [Alberto Mucci] |

Salvatore Casillo, a professor at the University of Salerno and the author of an upcoming book on the history of counterfeiting, told Al Jazeera that “there are historical reasons why Campania [the region of which Naples is the capital] is home to some of the best counterfeit artisans in the world.

“On the one hand, there is a certain difficulty in enforcing the law given the historical presence of [the Mafia].

“Counterfeiting is nothing new to Naples and the surrounding area. In line with an entrenched Italian tradition, a number of these print-makers inherited their skills from their fathers and family members involved in the counterfeiting business before them.”

This environment, together with the limited space needed for clandestine printing works, has made Campania the perfect location for counterfeiters to operate, Casillo said.

A major operation conducted by the Carabinieri on November 26 led to the arrests of 56 people affiliated with the Napoli Group and gave some insight into the organisation’s operating methods.

Clandestine operations

As Langella explained, counterfeiters usually operate on commission.

“They first receive an order for X million of fake euros, and only then set up a clandestine printing facility. These can be in hidden places such as behind a butchery or a car repair shop. Then, when the order is complete, the group dismantles the printing facility and waits for the next commission to arrive.”

Counterfeiting a new banknote does not take much time, given that digital technology … can reproduce any kind of original, including banknotes, even without specialised technical knowledge.

Counterfeited euros of smaller denominations are usually sold for about 10 percent of their nominal value, while those with higher face values are sold for a slightly smaller percentage. This is because 20 and 50-euro banknotes are less likely to be checked, and are therefore more easily distributed.

Over the past few years, the police have found fake euros produced by individuals linked to the Napoli Group in Germany, France, Romania and as far away as sub-Saharan Africa.

This has transformed the Campania counterfeiting phenomenon from a solely Italian issue to a European one – to the extent that the Napoli Group counterfeits are allegedly one of the reasons behind the ECB’s decision to issue new 5 and 10-euro notes with additional security features.

Printing 300-euro bills

Nevertheless, stopping the counterfeiters won’t be an easy task.

A Bank of Italy official, who asked to remain nameless, told Al Jazeera: “Counterfeiting a new banknote does not take much time, given that digital technology … can reproduce any kind of original, including banknotes, even without specialised technical knowledge. Yet, creating what is called an ‘insidious counterfeit’ [a hard one to detect] is difficult whatever the technology used.”

All one needs is an able print-maker and an initial investment of about 200,000 euros. The rest of the technology and material are easily and legally purchasable online.

A sign of the growing influence and arrogance of the counterfeiters was the recent discovery of a 300-euro banknote – a denomination that does not exist – believed to have been produced by the group and sold in Germany.

Information obtained by Al Jazeera from the Bundesbank, Germany’s central bank, shows that in 2014 the police busted several groups handling counterfeits and seized several mints producing fake euro coins.

Compared to the roughly 16 billion legitimate euro banknotes currently in circulation, the counterfeit ones make up a very small percentage: there is a less than one-in-100,000 chance of receiving a fake euro note.

Nevertheless, authorities across Europe regularly work together to respond to the growing problem. The Italian and German central banks confirmed that the ECB and the central banks of eurozone countries share a database to exchange information on counterfeit cases in real-time. The heads of counterfeit departments at the ECB level hold regular meetings as well.

When the euro first began circulating in 2002, it was heralded as a banknote nearly impossible to counterfeit.

The Napoli Group and the Italian art of arrangiarsi have shown this is not the case.