Music of survival in Mandela’s prison

Music transcended political, tribal and linguistic differences to unite an oppressed people during apartheid.

Johannesburg, South Africa – In his autobiography Long Walk to Freedom (1994), Nelson Mandela made a now-famous comment about the conditions in South Africa’s apartheid prisons, where, from the 1950s, hundreds of activists in the anti-apartheid struggle were incarcerated for protesting against the white government.

“It is said that no-one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails,” Mandela wrote. “A nation should not be judged by how it treats its highest citizens, but its lowest ones – and South Africa treated its imprisoned African citizens like animals.”

Mandela drafted his memoirs while jailed in the notorious maximum security prison of Robben Island, where, from 1964, he spent 18 of the 27 years he was jailed by the Nationalist Party for his part in fighting for racial equality and the eradication of apartheid.

Mandela died, aged 95, on December 5, 2013.

Details about the brutal and harrowing conditions for black, “coloured” and Asian political prisoners on Robben Island, which lies just off the coast of Cape Town at the foot of the African continent, are now well known.

Despite these conditions, political prisoners found ways to resist the authorities’ attempts to break their spirits and morale through a variety of recreational and cultural activities. One fundamental key to survival and prisoner resistance on Robben Island came in the form of music.

Musical resistance

In April 2013, Music Beyond Borders reunited a group of former political prisoners from Robben Island to sing their songs of survival.

Music already had become an essential part of the anti-apartheid movement, tracing the history of the struggle for democracy and evolving in direct response to the changing political climate and conditions across the country. In essence, the spiritual and human dimension of the liberation struggle was expressed through African vocal music and dance, especially with a rich repertory of freedom songs.

“Songs were inspirational, they create the mood,” said Anthony Suze, who was sentenced to 15 years on Robben Island in 1963 for his membership in the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) and for mobilising other students.

“So if you want to go into a fight, you sing,” said Suze, who became an avid soccer player in the Makana Football Association on the Island. “That song becomes the opium that takes over the body, mind and soul.”

In prison, where the different pillars of, and approaches to, struggle interlaced – mass local protests, underground struggle, armed military units, and international demonstrations – music transcended political, tribal and linguistic differences to unite an oppressed people against a common enemy.

“You cannot begin to think of waging a struggle, coming together – you come from different backgrounds, different orientations here and there, and you have to relate to each other in captivity – without a song,” said Mark Shinners, who served two 10-year terms on the Island for being a member of a banned organisation – the PAC – and for conspiring to overthrow the government. “It’s inconceivable. It’s a very bridging type of experience.”

In the single cells of Mandela’s block – which housed about 30 inmates of a prison population of nearly 800 – music was allowed only at restricted times.

|

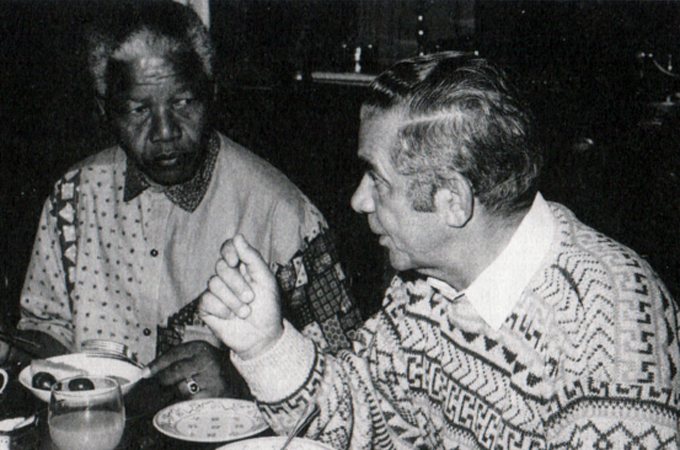

| Eddie Daniels, prisoner 864/64, with Mandela in 1991 [Eddie Daniels] |

Eddie Daniels a “coloured” from District Six in Cape Town who was sentenced to 15 years in 1964 for sabotage and being a member of the Liberal Party of South Africa and the African Resistance Movement, served his prison time with Mandela, Walter Sisulu and Ahmed Kathrada.

“Initially, it was very bad [on Robben Island],” Daniels recalled. “In detention, when you’re first arrested and tortured, people die. So everything is relative. When I got there I did not think I would survive.”

Daniels described how, after the first two or three years, the authorities allowed them to organise a concert on Christmas and New Year’s Eve. Each inmate presented a song – which could not be political – cracked a joke or recited poetry from his own isolation cell, which reverberated down the austere concrete corridor, while a master of ceremonies conducted the proceedings. Daniels usually sang Galway Bay , an Irish freedom song, whose memory still brings tears to his eyes, he said.

Mandela chose the traditional Scottish ballad, Bonnie Mary of Argyle , which Daniels still loves to sing. “Mr Mandela’s cell is down the way,” Daniels said. “And his voice floats up this grim corridor and it’s such a gentle voice and he sings this song.”

Other famous inmates contributed soulful songs from their own ethnic origins. Ahmed Kathrada, who recently accompanied US President Barack Obama on a tour of Robben Island, was charged in 1964 with sabotage and sentenced to life imprisonment at the Rivonia Trial alongside Mandela. He recalled how Laloo Chiba would sing the Hindi song, Pinjre ke panchhi , about the pain of the caged bird, popular with activists in the Transvaal Indian Congress who were detained and imprisoned in the late 1950s and 1960s.

Early on, the political prisoners in isolation sang African work songs, such as Shosholoza – a Ndebele folk song that originated in Zimbabwe but became so popular in South Africa that it is often referred to as the second national anthem. Songs from the struggle were also sung to raise their morale during back-breaking hard labour in a limestone quarry.

The prisoners also set up a choir in their isolation section, conducted by Joshua Zulu – a music teacher outside of prison – with about ten members, including Mandela, and Selby Ngendani who was well-versed in popular music.

The prisoners also enjoyed a daily music programme played by the warders over the intercom system, including musicians such as Miriam Makeba, Harry Belafonte, Joan Baez and Nat King Cole. The records were donated to the prisoners or they would buy them, gradually building up a library of some 250 LPs by 1975 . “We had been cut off from music for some years,” recalled Kathrada, “And when it started we were met with a barrage of pop stuff and for sometime we didn’t know what hit us. It all sounded like one hell of a big noise.”

Communitarian

But it was in the communal sections of Robben Island, where conditions were probably even worse than in the isolation cells, that a lively music-making scene thrived. Political and freedom songs had their place, especially to commemorate specific political events on the calendar, cultural days or particular holidays. The ANC freedom songs were mostly adaptations of wedding songs and hence joyous and exuberant, while PAC songs were often derived from devotional music and Christian hymns, such as Give a Thought to Africa , sometimes led by Dikgang Moseneke – now South Africa’s deputy chief justice – with an accompanying chorus of men.

Singing is part of the cultural life of South Africans, especially black South Africans, singing is part of our very rich culture.

However, the vast majority of music-making on the island was not politically oriented and instead created a profound sense of community.

“Singing is part of the cultural life of South Africans, especially black South Africans, singing is part of our very rich culture,” said Lionel Davis, who was sentenced in 1964 for seven years for conspiracy to commit acts of sabotage as a member of the National Liberation Front. “Every facet of our life is celebrated through music. So when you go to jail the tradition continues…When you are down, music uplifts the spirit, gives you hope… You cannot stop a political prisoner from talking; you cannot stop an African from singing.” As Mark Shinners so poignantly remarked: “You could sing your way out of pain and survive.”

Music took many forms, including the formation of choirs and bands. Ike Molete Makiti witnessed the Sharpeville Massacre first hand, when hundreds of police opened fire on thousands of black protesters in the township in 1960, killing more than 69 people and wounding nearly 200. The massacre marked the start of armed resistance in South Africa and drew international condemnation.

Makiti and David Ramagole were imprisoned in 1968 and 1969 respectively, and they later formed the basis of the Fortunes vocal quartet, going around different cells singing songs such as When the Moon Takes the Place of the Sun in the Sky ; as Makiti says, so “that they should forget about their worries from outside, just be with us in song”.

Prisoners also organised singing competitions and concerts of old and new pieces, such as a production of Handel’s Messiah and a new musical setting of the Sharpeville Massacre. They imported traditional indigenous South African performance genres, such as isicathamiya, from Zulu migrant workers, the a cappella singing style later made famous by Paul Simon’s Graceland and Ladysmith Black Mambazo. And they even made their own musical instruments out of whatever materials they could lay their hands on, such as a saxophone built by Nelson Nkumane out of dried seaweed from the beach next to the work quarry, an extraordinary feat given the gruelling circumstances.

These musical activities brought relief to the daily hard labour in the stone quarry, where African work songs provided both a rhythmic work pace – which could be slowed down musically to save energy – and a sense of unity. These drew on a long tradition of migrant labourers’ folksongs that were widespread in apartheid South Africa, offering satirical commentaries about their white oppressors and the state of the nation.

Ironically, the warders – most of whom had little knowledge of other African languages except Afrikaans – tolerated the prisoners’ singing, believing it helped them to work harder, while in ignorance of their true meaning.

Their interactions with the political prisoners were, in some cases, oiled by music-making, slowly leading to the breakdown of racial prejudices and the initiation of a process of reconciliation. “Ironically, it is in jail that we have closest fraternisation between the opponents and supporters of apartheid,” Kathrada wrote. “We have eaten of their food, and they ours; they have blown the same musical instruments that have been ‘soiled’ by black lips.”

Ultimately, music provided a positive force for resistance and survival, transforming Robben Island from a hell-hole of suffering, torture and abuse into a symbol of defiance and triumph of the spirit. Music on Robben Island provided yet another model of cultural expression that advanced social change and by individuals suffering and protesting the violation of human rights under oppressive regimes. It was an example akin to the recent rap and hip-hop commentaries from the Arab Spring revolutions.

“While we will not forget the brutality of apartheid, we will not want Robben Island to be a monument of our hardship and suffering,” Ahmed Kathrada forcefully concluded in 1993 after the liberation. “We would want it to be a triumph of the human spirit against the forces of evil, a triumph of wisdom and largeness of spirit against small minds and pettiness, a triumph of courage and determination over human frailty and weakness.”

This article was originally published in November 2013, and has been updated following the death of the South African leader on December 5, 2013.