Tunisian police accused of torture

Death of man in custody puts spotlight on country’s feared security forces.

Tunis, Tunisia – Walid Denguir, 32, left his house at 4pm to run an errand in the Bab Fellah neighborhood of Tunis. After arriving at a local garage on November 1 to change a tyre on his motorcycle, he was arrested by police. An hour later, he was dead.

It was another case of alleged police violence in post-revolutionary Tunisia, and comes amid escalating security concerns that highlight the need for police to protect Tunisians while preserving their rights.

Nearly three years after the overthrow of president Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, who used the security forces as a tool of oppression, many Tunisians still fear and distrust them.

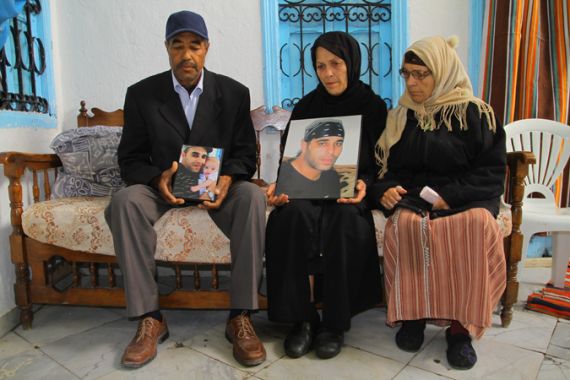

“My son was alive and well when he left the house,” Walid’s mother, Faouzia, told Al Jazeera.

Denguir’s family home is in the working-class Montfleury neighborhood of Tunis. His distraught grandmother sat in her slippers on the road outside a small shop, repeating to whoever would listen: “They killed my kid. They should be hung. They killed me.”

She walked through the maze of alleys to the Denguir home past graffiti reading “God rest your soul, Walid” and “cops are dogs.”

When I saw my son's body, he was completely disfigured.

Wearing a black robe and black headscarf, Faouzia said she was called about 5pm by someone identifying himself as a police officer. He told her Walid was dead.

When she arrived at the Wardia police station in southern Tunis, the police would not let her enter. She waited outside until a body was loaded into a waiting ambulance, and followed it to Charles Nicole hospital.

“I begged the guards at Charles Nicole to let me into the morgue,” she said, clasping her hands together.

Repeat abuse

Details of what happened between the time Denguir was arrested and when his mother saw his body are still unclear. Faouzia is convinced the police killed her son, and she said it was not the first time her family or the poor people of the neighborhood suffered from abuse at the hands of authorities.

She spoke in a shaky, exhausted voice as she sat down to recall her son’s death.

“When I saw my son’s body, he was completely disfigured,” she said. “His left arm and left leg were stuck in a bent position, while his right arm and leg were more stretched. I saw an injury behind his left ear, among other bruises, and handcuff marks on his wrists and ankles.”

Radhia Nasraoui, a lawyer looking into the case and a prominent human rights advocate, examined Denguir’s body and said it showed evidence of the “roasted chicken” position, in which the victim’s hands and feet are tied to a rod while the body is beaten.

The police, according to Faouzia, regularly break into her house and others in the neighborhood to rough up their sons. The door to the family’s home was damaged, which she said was a result of the police repeatedly breaking in.

“My son was known and loved around the neighborhood. He was never a troublemaker, you can ask anyone,” Faouzia said.

Representatives of the security forces have sought to discredit gruesome photos that have spread widely displaying Denguir’s wounds. They say the images were taken post-autopsy, and that the procedure is to blame for Denguir’s disfigurement.

“Naturally, the pictures taken [of Walid Denguir’s body] would show bruises and cuts, as they were taken after the autopsy,” Mounir Khmili, a spokesman from the main security forces union, told Tunisian radio station Mosaique FM.

Police officers in the neighbourhood, according to Khmili, “are doing an incredible job. We should not tarnish their reputation.”

He said the autopsy report, which Denguir’s family and observers say they have not seen, “refutes all accusations.”

On November 5, Tunisian newspaper al-Chourouk reported that Denguir’s autopsy revealed he died from a drug overdose from ingesting a large amount of cannabis. The family and human rights monitors, however, say they have not seen a copy of the autopsy report, and the possibility of dying from ingesting cannabis has been discredited.

No information

Faouzia refuted the security officer’s claims. She said she first saw the body on Friday evening before the Saturday autopsy, and the damage had already been done. She also denied that Denguir ever took drugs.

“We still have not received any information about the autopsy,” Faouzia said, adding Nasraoui told her supporters will have the body exhumed for another autopsy with foreign experts “if the autopsy doesn’t bring us justice.”

“I can’t trust Tunisian doctors,” she said.

Human rights monitors in Tunisia are also sceptical. Amna Guellali of New York-based Human Rights Watch has been following the case closely and done her own investigating, speaking with witnesses and officials.

“It is basically impossible that [the signs of torture on the body] could be from the autopsy,” Guellali told Al Jazeera.

The Ministry of Interior released a statement about the incident through TAP, the state news agency, on November 3, two days after Denguir’s death. The ministry said it “awaits the coroner’s report to determine the reasons of the death of a suspect, Walid Denguir, following the overuse of power exerted on him during the interrogation that led to his death.”

This statement, however, has since been taken down from the TAP website.

The ministry has reportedly ordered an internal review of the incident. In addition, a court of first instance, the first step in criminal prosecutions in Tunisia, is investigating Denguir’s death. Authorities have already spoken to witnesses, according to Guellali.

|

| An elite police officer patrols in Tunis in September 2012 [AP] |

Despite repeated attempts throughout the week to contact multiple offices within the ministry in person and over the phone, no one could be reached for comment.

‘Isn’t there justice?’

Almost three years after the revolution, monitors say security forces still operate with impunity. In September 2012, Abderraouf Khamissi died from injuries sustained while in police custody. Over a year ago, the officers said to be responsible for Khamissi’s death have yet to go to trial, but are being held in pretrial detention.

An anti-torture law passed by Tunisia’s National Constituent Assembly in early October has yet to be implemented, and even when it is it would only go so far in preventing cases such as Denguir’s, according to Guellali.

The law creates a commission of human rights experts, lawyers, and doctors with legal authority to inspect all detention centres in the country. Knowing their facility could be visited at any time could deter authorities from torturing suspects, according to Guellali. But a loophole in the law allowing authorities to deny access under certain circumstances is worrisome, she said.

Even if fully implemented, the law “might not have changed the outcome” in the Denguir case, Guellali said.

“We’ve seen repeatedly over the past month and before, since the fall of the regime, that the cases of violence exercised by the police toward people have not been investigated in a diligent and serious way,” she said.

The new law is of no condolence to Faouzia.

“I am divorced and suffered to raise my kids,” she said. “At the end, someone kills my son and continues to roam the streets free without even being suspended. Isn’t there law? Isn’t there justice?”