Indigenous tap new app to save old languages

A modern texting app released in Canada allows indigenous people to communicate in their native languages.

Concerned about the disappearance of indigenous languages, activist Pena Elliott thinks a new texting app could be the modern solution to preserving his native Saanich language.

“This new chat [software] is going to help our more fluent speakers a lot, because we’re able to type it in, we’re able to think in the language,” says Elliott.

“It helps you memorise it a lot more if you use it every day.”

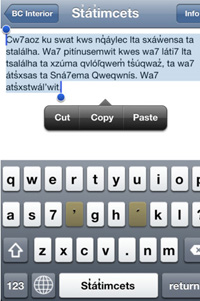

FirstVoices Chat, an app created for texting in native languages, was developed by an indigenous technology council on a Canadian native reserve in British Columbia.

It is the first app to contain custom keyboards for every indigenous language of Canada, Australia and New Zealand, as well as Navajo – the largest indigenous language group in the US.

Across Canada, there are at least 50 indigenous languages belonging to 11 language families. These languages reflect distinctive histories, cultures and identities linked to family, community, the land and traditional knowledge, linguists say. For many native people, these languages are at the very core of their identity.

|

“I ask every single Saanich person I meet in the street whether they use the app yet, and most of them say they do. If not, they download it right in front of me!” – Peter Brand, FirstVoices manager |

‘Many downloads’

The new technology means traditional knowledge can be expressed and preserved in a modern way.

FirstVoices manager Peter Brand said inspiration for the project arose from local Vancouver Island native communities.

Ever since texting became popular, Brand said locals have been asking the Council when they would be able to text in their own language. Since the app’s release, Brand has been surprised at the community response.

“I ask every single Saanich person I meet in the street whether they use the app yet, and most of them say they do,” Brand said. “If not, they download it right in front of me!”

Brand says he believes the texting app is part of a larger revival of the Saanich language in the last few years – particularly among the youth.

Disappearing speaker bases

Although the release of this app is billed as a high profile achievement for native groups in the fight to save indigenous languages, it’s only useful if people already know the dialects. For Canadian native groups, the trend of disappearing speaker bases over the last decades is alarming.

Over the last century or so, at least 10 languages have become extinct.

|

| FirstVoices texting app |

The percentage of Canada’s indigenous population who are able to converse in at least one indigenous language in 2006 (the last census completed) was just 22 per cent.

Many factors contribute to the erosion of speaker bases across the country, including increasing migration between reserves and cities, linguistic intermarriage and the prevailing influence of English and French in daily life.

In spite of this trend, there is a passionate group of Native people across the country who have been working to save indigenous languages in their own communities.

For them, the struggle is not just about saving words, but the ideas and knowledge that would disappear along with the words.

One member of that group is Professor Lorna Williams of the University of Victoria, from the Lil’wat First Nation. Williams, who has years of experience in language revitalisation and Aboriginal education, believes that language is “fundamental” to a person’s way of life – not only among Native people, but for everyone.

“Languages all over the world are valuable to all humans because that’s where the fundamental and intimate knowledge of that land resides,” Williams explained.

Breaking the trend?

Of Canadian indigenous languages, Cree is considered to be one of the least endangered because of its relatively large speaker base. Language rights activists, however, are still concerned.

Reuben Quinn, a Cree language teacher based in Edmonton, says that he has spoken with some of the people counted in surveys as proficient Cree speakers.

“I lose them within a few words. They can’t even carry on a conversation,” Quinn said. “I’m quite panicked.”

Quinn’s panic is, again, not over the loss of words. He explained that there are two forms of Cree – common and high Cree. Most of the people counted as speakers in the survey are only able to speak common Cree.

But it is high Cree that expresses ideas about creation, balance with the environment and an intricate spirituality; this is what Quinn teaches at the Centre for Race and Culture.

|

“As Indigenous peoples around the world, we need to keep our cultures alive; we need to preserve our identity.“ – Christine Fredericks, Indigenous artist |

“Spirituality is peppered throughout the language and syllabic system,” Quinn explained. “The Cree language system teaches us that when we are gone the earth will still be here, but what are we leaving behind for the seven generations?” Quinn asked.

Reclaiming the language

For indigenous people who don’t live on reserves, the app will help keep them connected to the language and other speakers.

Christine Fredericks, an indigenous artist, has not lived on the reserve for years and considers herself an “Urban Aboriginal”.

Living off reserve impacts the likelihood of knowing an indigenous language – of those living on reserves, about half say they can speak at least one; compared to just 12 per cent of those living off the reserves.

Fredericks is one of many who are breaking the trend by learning their indigenous dialect as a second language instead of a mother tongue.

High Cree is still spoken by spiritual elders, but it is the youth who must learn the language for it to be able to survive across generations.

“They are really desperate to pass along the sacred knowledge and are thwarted by the fact that younger Cree don’t know high Cree. If this continues, we will lose the most sacred parts of our culture,” Fredericks said.

The texting app can help in this struggle, activists say, because the youth are likely to download it and use it on a daily basis. And if they can hold on to the language, they say, traditional knowledge is more likely to survive across generations.

“As indigenous peoples around the world, we need to keep our cultures alive; we need to preserve our identity,” Fredericks said. “If we can’t, the whole world will be worse-off.”