Kazakhstan: Election under a cloud

Violence, intimidation and regulatory manipulation may undermine any steps toward democracy in the central Asian nation.

|

| Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev portrayed the election as a step towards democracy [GALLO/GETTY] |

Mangistau, Kazakhstan – Kazakhstan’s parliamentary elections are taking place under a cloud – following a campaign that began with the worst political violence the country has seen in a generation.

The fatal shootings in December of at least 17 civilians in protests in the oil-rich (but economically deprived) region of Mangistau in western Kazakhstan have overshadowed the vote, which the president’s Nur Otan party is expected to dominate.

President Nursultan Nazarbayev’s administration has attempted to portray the election as a step forward for democracy – with the expected addition of a second party to the country’s legislative chamber – but foreign observers such as the OSCE have never judged Kazakh elections either free or fair.

The southern city of Zhanaozen has been under martial law since December 16, when at least sixteen people died and almost 100 were wounded in clashes between police and oil workers sacked from the state oil company, KazMunayGas.

Hundreds of workers had been on strike over pay and conditions for more than six months – but their action was earlier declared illegal by the authorities and nearly 1,000 were sacked. A further 1,000 workers from another oil field were also fired for an illegal strike action.

Before a confrontation with police turned violent on December 16, strikers had been holding a peaceful occupation of the main square in Zhanaozen, night and day, since early July.

Violence

On December 17, police opened fire on oil workers blocking a railway in the town of Shetpe, a protest held in solidarity with the Zhanaozen strikers, killing at least one more protester.

|

|

By day, Zhanaozen’s residents go about their business under the watchful eye of the security services. Police in body armour and riot helmets patrol the streets.

By night, people remain at home under curfew. Zhanaozen is under a state of emergency. Those caught outside after nightfall risk being detained by police. That is a risk everyone wants to avoid.

At least two reports of suspects dying from beatings in custody have been recorded.

Such cases have fuelled suspicions that the death toll may ultimately be higher than the official figures. But with the town under a state of emergency until the end of January, and restrictions on movement and information sharing, the true figure is impossible to verify.

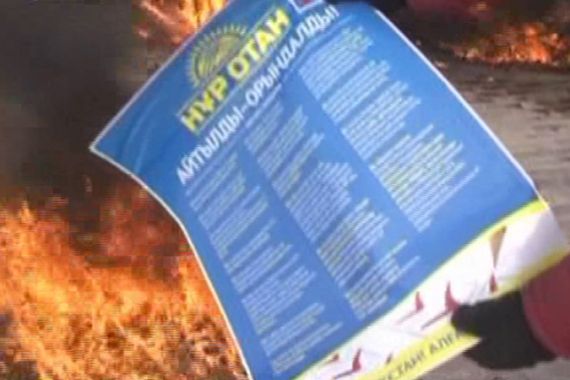

Initially, the country’s Constitutional Council ruled that parliamentary elections scheduled for January 15 could not go ahead in Zhanaozen. Then in a surprise move, President Nursultan Nazarbayev overturned the decision. Yet TV pictures have shown protesters burning posters of Nazarbayev’s ruling party during the riots.

Striker Sersen Aspentaev was shot in the leg in the disturbances. He said he was carrying other victims to safety when a round entered his left thigh – and he will not be going out to vote.

“I never voted – before the violence I didn’t vote for Nazarbayev and I won’t now,’ he told Al Jazeera. “After everything that they’ve done, what kind of voting can you have?”

Media blackout

It is difficult to gauge public opinion towards what happened. State media has consistently portrayed the government line: That so-called outside forces intent on destabilising the country organised and stoked the violence, while strikers have been described as “hooligans”.

That is an opinion shared by local lawyer Irina, who works in the regional capital Aktau.

“They’re selfish and stupid people who were asking too much,” she said. “The lack of order meant that the government was right to shoot. You shouldn’t bite the hand that feeds you. Just as happened in Uzbekistan when there was unrest the government used force, and now you have stability there.”

But Professor Sebastien Peyrouse, EUCAM researcher and senior research fellow at the Central Asia and Caucasus Institute, says a very significant share of the population in Kazakhstan are aware of the social stakes connected to the poor distribution of oil wealth in the country, in particular in western regions.

“Many support the workers’ claims, the right to organise freely in unions – and condemn the police violence. The events of Zhanaozen will therefore weigh indirectly on the elections, even if they will not come through in the official results.”

That is something President Nazarbayev appears to have taken on board. His reaction to the violence was decisive, if belated. He has fired senior officials of the state oil company and the heads of local government.

The dispute over pay and conditions had dragged on for months without resolution, and the president has ordered that all oil workers who were fired be given new jobs.

New accusations

But in contrast to the promises to rehabilitate the strikers, around a dozen strike leaders are being held in detention. Some have been accused of receiving funding from dissidents abroad and face charges of inciting social hatred. They could face long prison sentences.

Mangistau’s newly appointed regional governor Baurzhan Mukhamedzhanov says two new state oil company subsidiaries will absorb the workers sacked for striking, and that any allegations of police brutality will be investigated.

“The main purpose of the police and security services is to prevent such kinds of disorder but if not – to resolve them the right way,” he said. “There were mistakes. Now there is a commission to investigate the activity of police. Could they have used alternative means, such as water cannon, to disperse the crowd and avoid shooting?”

So far, no police officers have been suspended pending any investigation into their actions. Although the president has promised to allow UN human rights investigators in, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights is still waiting for an official invitation.

Bulat Abilov, a leader of the opposition party OSDP Azat said the violence had weakened President Nazarbayev.

“The authorities had no need to shoot people. It shows they were afraid – and all dictators who rule this way finish the same way,” he said. “Their time has come. They have shown their ineffectiveness and their inadequacy.”

Illusions of democracy

But he and other opposition politicians are unlikely to capitalise on the tragedy at the ballot box. The Central Election Commission this week barred both him and another Azat leader from running in the elections over a technicality. ALGA!, another credible opposition party, has been unable to register.

Instead, the recently formed party, Ak Zhol, which has close ties to the administration, is tipped to win seats in Sunday’s poll. Its leader, Azat Peruashev, is a former Nur Otan member and business associate of the president’s son-in-law.

According to Prof Peyrouse, President Nazarbayev has adopted a similar political strategy to the kind employed by Putin’s Kremlin.

“Nazarbayev hopes to create several political formations to give an air of competition, as he knows that Nur Otan’s mono-party status delegitimises it,” he said. “We are thus not dealing with any real democratic reform here, but instead the creation of a second party to represent the business elites.”

Unlike elections, the violence in Zhanaozen has presented Nazarbayev with perhaps the most significant political challenge of his career. His officials acknowledge that the root causes behind the unrest lie in entrenched corruption, social inequality and under-investment.

Infrastructure has been poorly developed. Many small towns – particularly in the west of the country – lack decent schools hospitals, or adequate housing. Despite all the oil riches the region produces – much of the wealth has gone elsewhere.

Governor Mukhamedzhanov says conclusions must be drawn from what happened. “We must learn lessons. Any dispute can be resolved through dialogue. Maybe it takes time but you have to speak to each other.”

Zhanaozen is an isolated desert city with poor links to the rest of the country. The unrest has been contained, but an atmosphere of fear there now prevails. In the face of a crackdown on the strike leaders, the promise of conciliation has yet to be followed up by concrete action.

There have been pledges of state aid, and new management at the state oil company has promised to improve relations between workers and employers. Meanwhile, the authorities know that there are other cities in Kazakhstan where the events of Zhanaozen may be repeated.

Follow Robin Forestier-Walker on Twitter: @robinfwalker