No end in sight for oil in the Gulf of Mexico

Fresh oil seepages raise questions about further problems with BP’s damaged oil well.

|

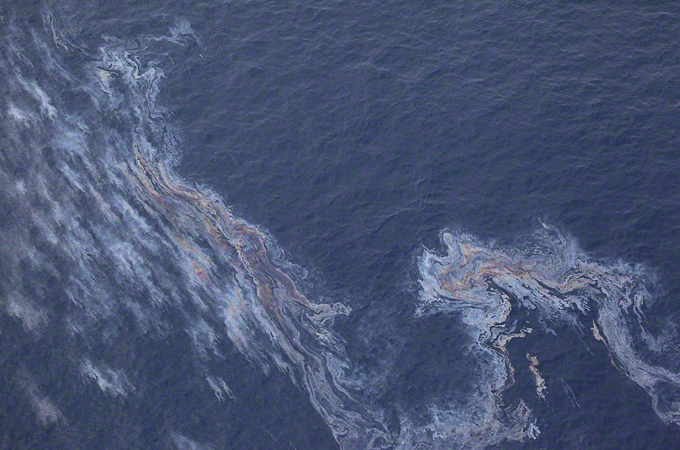

| Thick oil sheen in the Gulf of Mexico, approximately 19 km northeast of BP’s stricken Macondo well [Erika Blumenfeld/Al Jazeera] |

Fifteen months after BP’s crippled Macondo Well in the Gulf of Mexico caused one of the worst environmental disasters in US history, oil and oil sheen covering several square kilometers of water are surfacing not far from BP’s well.

Al Jazeera flew to the area on Sunday, September 11, and spotted a swath of silvery oil sheen, approximately 7 km long and 10 to 50 meters wide, at a location roughly 19 km northeast of the now-capped Macondo 252 well.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsAfter the Hurricane

World’s coral reefs face global bleaching crisis

Why is Germany maintaining economic ties with China?

According to oil trackers with the organisation On Wings of Care, who have been monitoring the new oil since early August, rainbow-tinted slicks and thicker globs of oil have been consistently visible in the area.

“BP and NOAA [National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration] have had all these ships out there doing grid searches looking at things, so hopefully now they’ll take a look at this,” Bonny Schumaker, president and pilot of On Wings of Care, told Al Jazeera while flying over the oil.

Schumaker has logged approximately 500 hours of flight time monitoring the area around the Macondo well for oil, and has flown scientists from NASA, USGS, and oil chemistry scientists to observe conditions resulting from BP’s oil disaster that began in April 2010.

Edward Overton, a professor emeritus at Louisiana State University’s environmental sciences department, examined data from recent samples taken of the new oil.

Overton, who is also a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) contractor, told Al Jazeera, “After examining the data, I think it’s a dead ringer for the MC252 [Macondo Well] oil, as good a match as I’ve seen”.

He explained that the samples were analysed and compared to “the known Macondo oil fingerprint, and it was a very, very close match”.

While not ruling out the possibility that oil could be seeping out of the giant reservoir, which would be the worst-case scenario, Overton believes the oil currently reaching the surface is likely from oil that was trapped in the damaged rigging on the seafloor.

He said the oil could either be leaking from the broken riser pipe that connected the Deepwater Horizon to the well, or that oil is leaking from the Deepwater Horizon itself.

But other scientists remain concerned that the new oil could be coming from a seep from the same reservoir the Macondo well was drilled into. The oil field, located 64 km off the coast of Louisiana, is believed to hold as much 50 million barrels of producible oil reserves.

Natural oil seepage in the Gulf of Mexico is a natural phenomenon and can cause sheens, but the current oil and sheen is suspect due to their size and location near the Macondo well.

“From what I’ve seen, this new oil and sheen definitely seemed larger than typical natural seepages found in the Gulf of Mexico,” Dr Ira Leifer, a University of California scientist who is an expert on natural hydrocarbon oil and gas emissions from the seabed told Al Jazeera. “Because of the size and its location, there is a greater concern that should require a larger public investigation.”

Fishermen and residents of the four states most heavily affected by BP’s disaster continue to struggle to regain a sense of normalcy in their lives. Many continue to experience health problems they attribute to chemicals in BP’s oil and the toxic dispersants used to sink it.

Shrimpers and oyster fishermen have seen their catches drop dramatically, and in some areas entire oyster populations have been annihilated.

“Crabs are dying in fishermen’s traps, and of those that make it to the docks, 40 per cent of die before they can be sorted,” Dr Ed Cake, a biological oceanographer, as well as a marine and oyster biologist, told Al Jazeera while on a fact-finding mission to check oyster beds for signs of recovery.

Al Jazeera asked Cake how the shrimping industry in Louisiana was doing.

|

| Shrimp boats at dock in Louisiana during prime fishing season. The seafood industry continues to be severely affected by BP’s oil disaster [Erika Blumenfeld/Al Jazeera] |

“The issue with the shrimpers is that the spawning ground for the shrimp was out where BP used most of the dispersants to sink the oil,” Cake said. “As far as how the industry is doing?”

He pointed to rows of shrimp boats tied up to a nearby dock.

BP’s Gulf of Mexico disaster is, to date, the largest accidental marine oil spill in the history of the petroleum industry. BP has used at least 1.9 million gallons of toxic dispersants to sink the oil, in an effort the oil giant claimed was aimed at keeping the oil from reaching shore.

The dispersants are banned in at least 19 countries, including the UK.

Meanwhile, fresh oil, either from natural seeps, oil platform wreckage, the Macondo 252 reservoir itself, or all four, continues to flow into the Gulf of Mexico.

Natural seeps

Al Jazeera spotted two BP research vessels in the area in question.

“These vessels are conducting research on natural oil seeps as part of the Natural Resources Damage Assessment [NRDA] process,” Tom Mueller, a press officer with BP America, told Al Jazeera. “They were parked over a known natural seep on the bottom of the Gulf, collecting samples and documenting the natural seep activity in that area using a remote operated submarine and acoustic sensing equipment.”

According to Mueller, the intent of the NRDA study is to learn more about the locations of natural seeps and test samples taken from them, and the current study should conclude the end of October.

|

| A BP research vessel floats in oil sheen in the area near the site of the April 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster [Erika Blumenfeld/Al Jazeera |

BP, whose Macondo well gushed at least 4.9 million barrels of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico last year after the Deepwater Horizon rig exploded and sank to the bottom, has denied that the oil is coming from their well.

“We can tell you that we recently sent a remote operated submarine down to inspect the Macondo well cap and the relief well cap,” Mueller, added, “Both are intact and show no evidence of any oil leak. So no oil is leaking from the Macondo well.”

Leifer remains concerned that the seep, given its proximity to the Macondo well, could be oil in the reservoir that entered a layer of mud and has migrated into a natural pathway that leads to the seabed.

“I see these new observations [of the seep] as the canary in the coal mine that indicates something could be changing at the seabed and should not be ignored and hope it goes away,” he said.

Given Overton’s findings that the oil does appear to be from Macondo, Leifer added, “It’s not necessary to be alarmist, but this is something that deserves setting an alarm off to investigate”.

His concerns are that if the seep increases in volume, “It could be a persistent, significant, continuous oil spill again, and that would require BP to go back and re-drill, and block off the pipeline even deeper than they already did, or else they would be liable for whatever the emissions are, forever, because it’s not going to stop for a very long time”.

Dr Ian MacDonald, a professor of biological oceanography at Florida State University who uses satellite remote sensing to locate natural oil releases on the ocean surface, confirmed that there are natural seeps in this region of the Gulf of Mexico, but believes more investigation is necessary in order to determine the cause and source of this particular site.

“The question for science is: Are the rates of seepage consistent with what they were prior to the blowout?” MacDonald told Al Jazeera. “Is the amount of oil we’re seeing now unusual with respect to historic levels? Can this oil be traced back to these formations?”

Anthropogenic seeps

MacDonald sees the heightened attention to the way the oil industry operates in the Gulf of Mexico that occurred as a result of BP’s oil disaster as a silver lining, but said, “It’s never the case that the natural processes [seeps] excuse pollution that human activities add to the water”.

He added, “The ecosystem is adjusted to the natural seeps, and the bottom communities have adapted over thousands of years, and that’s not the case with these blowouts”.

Leifer, like MacDonald, pointed to the natural seeps in the area.

“There is natural migration in the area around Macondo, and one of the sites we’ve studied is MC118, about 18 km away,” but added, “The concern is not that human activities caused a fault, but by creating pathways outside the [well] casing, they are allowing oil to travel along the well pipe then migrate horizontally until it intersects an existing vertical fault migration pathway, then reach the sea bed.”

His concern, shared by other scientists, is the possibility that the volume of oil flowing from the seep, if it is related to the Macondo area, could increase with time.

“We should be having sonar works done of that area, and the public needs to be informed of the findings,” Leifer said. “That survey should be repeated every three or six months to confirm that the seepage is not becoming larger and more widespread.”

‘Worst crisis I’ve ever seen’

As concerns about the possibility of new oil persist, fishermen and scientists continue to deal with the aftermath of BP’s disaster.

“We are in the worst crisis I’ve ever seen,” Brad Robin, a sixth-generation fisherman and seafood proprietor told Al Jazeera while out on a boat surveying the crippled oyster population where he fishes, “The [oyster] industry might do 35 per cent this year.”

Dr Cake, who along with University of New Orleans oyster biologist Prof Tom Soniat, invited Al Jazeera to accompany them, Robin, and Robin’s son Brad along to check for recovering oyster populations.

The marsh area outside of Yslovskey, Louisiana, was severely affected by massive fresh water diversions that were made from the Mississippi River. The choice was made in an effort to flush the marsh in order to prevent oil from washing in, but the fresh water has killed all the oysters, and Cake believes dispersed oil came in anyway.

Further complicating things, Cake has pinpointed at least two invasive species that do not bode well for a recovery of Louisiana’s oysters.

|

| Dr Ed Cake, left, has identified at least two invasive species that could have a devastating impact on the Gulf of Mexico’s oyster industry [Erika Blumenfeld/Al Jazeera] |

“We are finding sponges growing on our oysters,” Cake told Al Jazeera, “They encrust the oyster shell and that prevents new spat [baby oysters] from attaching to grow new oysters. We don’t know why this is happening, but we think it came in response to the fresh water and oil. This is the first time we’ve seen it.”

The sponge is chalinula loosanoffi, and is from Ireland, the upper East Coast of the US, and in The Netherlands.

Cake has also found a worm, poydora aggregata, from Maine, that attaches itself to oysters and fouls their shells.

“I’m worried these sponges and worms could wreak havoc on the industry,” Cake said.

Last year’s oyster harvest in Louisiana was cut in half, to a 44-year low, due to BP’s oil disaster. Scott Gordon, Mississippi’s director of the Shellfish Bureau of the Office of Marine Fisheries, said this summer, “I fully expect to have 100 per cent mortalities of the oysters in the western Mississippi Sound”.

Prof Soniat explained that the oyster industry is afflicted with “multiple impacts”.

“First the oil spill took away their fishing season,” he said of the banning of fishing in the wake of BP’s disaster. “Second, the fresh water diversion took away the oysters; and third, the program of having oystermen harvest shells from their leases to try to re-seed other areas killed the oyster reefs.”

Meanwhile, concern over ongoing oil seeps, whether they be natural or anthropogenic, persists, and scientists are calling for further investigations.

“I don’t understand why we’re seeing so much more oil out there right now than we’ve seen in the past,” MacDonald said. “We need to dig in and investigate and see what is going on.”

Leifer said that the amount of oil out near the Macondo site “definitely seems larger than typical natural seepages found in the Gulf of Mexico; both because of that and its location, there is a greater concern that should require a larger public investigation”.

The possibility that brings the greatest concern is that oil is leaking from the reservoir straight out of the ground. This situation could be impossible to stop, because the vent would increase in size over time due to the highly pressurised reservoir.

Follow Dahr Jamail on Twitter: @DahrJamail

See a photo gallery of the current oil leaks in the Gulf of Mexico.