For Pakistan, monsoon rains bring fresh fears

Yet to recover from last year’s devastating floods that left millions homeless,the country braces for heavy rainfall.

|

| The UN says two to five million people could be affected by this years floods [GALLO/GETTY] |

Last summer, devastating floods caused by heavy monsoon rains swept across Pakistan, disrupting the lives of close to 20 million people. Nearly 2,000 Pakistanis were killed, 1.5 million houses were destroyed and over 11 million people displaced from their homes.

“The world has never seen such a disaster,” UN secretary general Ban Ki-moon declared during a visit to the flood affected areas.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsTurtles swimming to extinction in Malaysia as male hatchlings feel heat

Could shipping containers be the answer to Ghana’s housing crisis?

Thousands protest against over-tourism in Spain’s Canary Islands

Most of the displaced have returned to start rebuilding their homes, government and UN officials say. But some had nothing to return to, so they remain in displacement camps. Those who did return fear that they might lose it all once again.

The Pakistani government and the United Nations have sent out flood warnings already as the Monsoon season this year arrived a week earlier than usual. Heavy rains will continue through most of July and August as the monsoon moves from northern India and sweeps across Pakistan.

History to repeat?

The UN says that in the most likely of scenarios, 2.7 million people will be affected by this year’s floods in one way or another. In the worst case scenario, as many as five million people could be in need of help.

Millions of people affected by last year’s devastation are still in a fragile stage of recovery and additional millions have recently been displaced due to violence and military operations in the country’s north west, where a growing insurgency is eroding government control.

The country also faces economic stagnation; Pakistan owes at least $59bn dollars to various agencies and it is safe to say that the country is bracing for another grave humanitarian situation.

| ||

“Pakistan is disaster prone, with a natural fault line running from south to north of the country,” said Manuel Bessler, country head of UN Office for the Co-ordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA).

A repeat of flooding of last year’s scale is unlikely. Pakistan’s Metrological Department expects 10 per cent less rain fall than usual, except in certain areas where the rainfall will be above normal.

“We are not expecting country-wide flooding, but some localised flooding,” said Arif Mehmoud of the Meteorological Department. “But it is difficult to tell at this point. We have to wait and see.”

Pakistan was heavily criticised for its slow reaction to provide relief last year.

A state of emergency was not declared early on. People were particularly annoyed by the fact that President Asif Ali Zardari went ahead with his trip to Europe, flashing smiles at cameras as most of the country drowned in water.

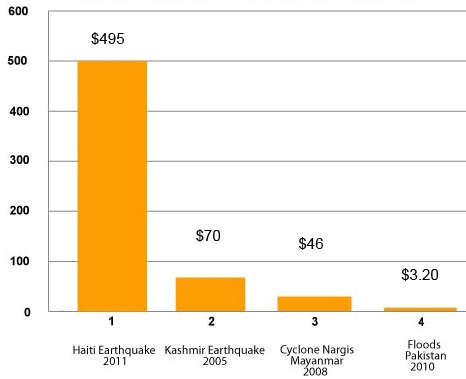

The UN, despite desperate attempts, could not collect the funds it required to meet the immediate needs of the millions affected. Ten days into the disaster, the UN only had $3.20 per person- an abysmal sum compared to $495 for the 2011 Haiti earthquake.

“From last year’s floods, we have learned our lessons,” said Bessler. “We, the humanitarian community and the government, have to be better prepared.”

Vulnerabilities

Since February this year, different branches of the Pakistani government, the UN and other aid agencies have met regularly to draw contingency plans for disaster relief.

“We have been developing scenarios of what could possibly happen,” Bessler said. “Our most likely scenario is that about 2.07 million people will request help in one way or another. In the worst case, up to 5 million people can be in need of help—their life stock will be lost, their schools will be swept away, or they will get displaced.”

While low safety standards in construction and frail dams make a large part of the country vulnerable to floods, the UN is most concerned for mountainous areas in north and north west – particularly Khyber Pakhtunkhwa – where heavy currents could cause tremendous damage.

| |

| Certain areas are particularly prone to monsoon floods |

“Mudslides could wash away bridges and roads and cut off villages again,” Bessler said. It is in these areas that rainfall is expected to be more than normal.

“Our seasonal forecast for rainfall is 10 per cent below normal, but in some areas – like Punjab, Kashmir, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa – it seems to be more than normal,” says Mahmoud of the Meteorological department.

“Last year, we struggled to bring water and medical equipment to these areas,” says Bessler. “We did not have enough containers to store drinking water, so we have made that one of our priorities this year.”

Co-ordinators for relief efforts say security is a concern in providing aid to five of Pakistan’s administrative units. In Balochistan, Khyber Pakthunkhwa, FATA and parts of Sindh and Punjab the “security situation (is) limiting access and presence of humanitarians,” the Inter-agency Contingency Plan for the Monsoon Season declares.

“It is absolutely not safe for us to go there directly,” one aid worker said about FATA. “We have to be accompanied by local forces or the army.”

Politicised aid

Analysts and aid workers are concerned that in areas where the government struggles to provide aid, often times insurgent organisations step in. In the process, they establish themselves a support base among local residents.

Dr Mohamad Taqi, a physician who writes regular columns for the Daily Times newspaper, was travelling with a group of doctors to provide aid in the aftermath of the 2005 earthquake.

“The first ambulance that I saw had ‘Al-Rashid Trust’ written over it and an army lieutenant was hanging on it as it passed in front of us.”

Al-Rashid Trust has been on the UN sanctions list since October 2001 for allegedly being involved in financing of al-Qaeda and the Taliban. “The Trust also had links to militants in Kosovo,” the UN sanctions committee says on its website.

“In the Balakot region of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, there was probably only one or two group of secular aid workers,” Taqi said.

In Pakistan’s north west – particularly FATA, where insurgent groups already have a stronghold, the fear of exploitation is even more real. People in desperate need of aid could be courted by extremist groups if mainstream aid organisations fail them.

“Most extremist groups have the Hizbullah model in mind—they organise along social service line and it is easy for them to step in when there is humanitarian need,” Taqi said. “Unfortunately, our social and secular parties do not have that structure and are no help in crisis.”

“In a disaster situation like last year, all hands on deck are needed and we appealed to any humanitarian agency to come and help,” said UN’s Bessler. “But of course it is a concern. Some groups claim humanitarian assistance but have other political agendas.”

Bessler, however, points to the fact that several religious groups were doing tremendous work in providing relief in last year’s disaster.

“It is not for the UN to censor who is political and who is humanitarian. That is the government’s job.”

Correction: The initial map in the article highlighting areas “prone to monsoon floods” had inaccurate border demarcations. The map has been corrected and we apologize.

Follow Mujib Mashal on Twitter: @mujibmashal