MF Hussain: The legacy of painting India

Celebrated Indian artist, exiled during his final years by attacks from Hindu right,leaves a rich legacy at home.

|

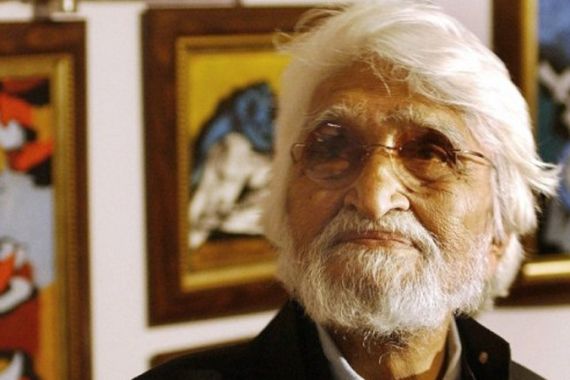

| Members of the Indian art community remember MF Hussain [AFP] |

He was one of India’s most renowned artist and his paintings fetched millions of dollars at international auctions. But he did not have a studio and walked barefoot most of the time.

“Wherever you go, the first thing they see is your footwear, then they will decide your status,” he told al Jazeera in an interview last year. “I said ok, you recognise me as I am.”

Maqbool Fida Hussain died in self-exile in London on June 9 at the age of 95, leaving behind close to 40,000 paintings, an open debate about the state of India’s democracy, and tremendous respect for Indian art on the international stage.

“On different levels, Hussain made the idea of a contemporary artist real in India – an artist as a wandering free spirit, but he also made the market,” says Ram Rahman, photographer, art-activist – and a friend of Hussain.

“He always believed that Indian art had not been given its due recognition,” says Dadiba Pundole, whose Pundole Art Gallery in Mumbai has exhibited Hussain’s work since the 1960s. “So he tried to push the boundaries, not only in his style and subject matter, but also in how exhibitions were presented.”

Despite having a remarkable body of work displayed in museums and galleries around the world, friends say Hussain saw himself as a folk painter. A globe-trotter, Hussain constantly moved around, painting wherever he felt a spur of inspiration and often leaving behind a mark of his work.

“He worked 18 hour days at times, but he did it his way,” Pundole says.

Hussain constantly drew for newspapers and for his favourite restaurants around India where he dined. “If an inspiration came to him while having a cup of coffee, he would call for a canvas and brush – or even chalk and blackboard,” says Rahman. Numerous small cafes around India have precious sketches and paintings of his hanging on their walls.

“He was an exceptionally modest man,” remembers Dr Oliver Watson, the former director of Qatar’s Museum of Islamic Art. In 2008, the museum exhibited a series of Hussain’s paintings, the beginnings of a relationship with the country that would end with Hussain dying a Qatari citizen. Watson says the artist personally saw to the hanging of each piece.

“He took a pen and wrote the captions and details of each piece by hand on the wall next to it.”

Humble beginnings

Born in 1915 in Western Maharashtra, Hussain was raised by his grandfather, who fixed lanterns for a living. His father remarried after his mother passed away before Hussain was two years old.

| IN VIDEO |

|

|

| MF Hussain spoke to Al Jazeera’s Riz Khan on the program One on One in 2010 |

As a child, painting was one of Hussain’s hobbies, soccer being the main other. He never had much interest in formal schooling or acquiring a degree.

“This brush in my hand – if nothing happens, I will whitewash the wall of the people – but I will never leave this,” Hussain recalled telling his father.

When he was seventeen, Hussain moved to Bombay. He slept on pavements while he searched for work. His love for the movies landed him a job as a painter of cinema hoardings. The skills that he learned working with large brushes and expansive canvases would become a trademark of his art that always sided on grandiosity.

In the 1940s, when Hussain made his first splashes as an artist, the art scene in Bombay was quite small. Dominated by well-educated figures such as Francis Newton Souza of the Progressive Artists Group, they looked towards European Modernism for inspiration. Hussain, who was discovered by Souza, came onto the scene with an entirely different mentality.

“Hussain came from a humble background, a really working class,” says Rahman. “What distinguished him right away was that he brought the subject of working class and a theme of ordinary life.”

By the 1970s, Hussain had grown to prominence, exhibiting alongside artists such as Pablo Picasso. His focus on distinctly Indian themes brought Indian art to eminence at the international level as he began appearing in exhibits and auction houses.

“Hussain, more than anyone else, really delved into the vast corpus of Indian mythology,” says Rahman. “Ever since he was a child, he had grown fascinated with the tales of the Ramayana. He even acted in some performances as Hanuman when he was a child.”

The other fascination of his art was the female form. And in his search for the perfect form, he watched a movie featuring Madhuri Dixit, the Indian actress and Hussein’s friend, sixty seven times. Each time in a theatre.

“The whole search in the female form is for my mother,” Hussain said in interview.

The exile years

In 1996, at the height of communal violence in India, Hussain became a target of the Hindu right wing. An article in a Hindi magazine that dug up a series of nude paintings of Indian goddesses from the 1970s became the basis for calls of blasphemy. His home and several galleries that displayed his work were attacked by violent protestors. Under the auspices of Shiv Sena, the Hindu right wing political party, numerous cases were filed against him in local courts that were then sent to Delhi. MF Hussain, all of a sudden, was the villain.

“It was not Hussain who attacked Hindu religious sensibilities,” says Bruce Lawrence, professor of religion and humanities at Duke University. “It was politically minded Hindu right wing activists that made him their special project for vilification, harassment and destruction of his art or threats to those who exhibited it.”

Ram Rahman points to the fact that such campaigns had started long before they turned on Hussain. The destruction of the Babri Masjid in 1993 is a prime example. “The Hindu right tried to reframe the notion of modern Indian culture, impose a mono-culture that was Hindu and excluded Muslims, Christians, and even Buddhists,” Rahman says.

“He was a soft target for he was a practicing Muslim at the height of his career and popularity,” Pundole agrees. Despite the controversy, Pundole’s gallery continued to display Hussain’s paintings throughout the period. “Not to prove a point, but simply because of the quality of his art.”

A narrowly partisan group intensified a massive campaign against him, displaying his nude paintings of goddesses along with fabricated titles and captions. They also coupled the paintings next to Hussain’s fully-clothed depictions of female Muslim figures, claiming Hussain was deliberately defaming Hindu goddesses.

“He was never a radical artist, not attempting to shock anyone,” says Rahman. “He was not trying to go against traditional iconography, rather he followed traditional iconography.” Rahman points to the fact that traditional sculptures of Indian goddess, even in temples, are bare-breasted. There are numerous depictions of the goddess Kali in the nude. For Muslim depictions, there is no tradition of nudes. Hussain simply followed the existing iconography, said Rahman.

“In Calcutta … all these goddesses, there are thousands of them already there,” said Hussain himself. “I wanted to communicate. I thought my metaphor, my images should connect with the greatest Mahabharata and Ramayana, which is the folklore of the country.”

In his defence, Hussain also pointed out that the attacks on him were not from religious specialists. “They [religious gurus] have not spoken a word against my paintings, and they should have been the first ones to have raised their voices. These politicians, who have nothing to do with religion, take out all these rath-yatras “processions”], for political reasons only,” he said.

As the attacks on Hussain increased and other political parties did not resist the Hindu right – fearing they would lose votes for being soft – Hussain moved to Dubai in self-exile. He spent his final years shuttling between Dubai and London.

At the time of his death, 95 years old, he was working on three major projects: a history of Indian civilisation, a series of paintings on Arab and Islamic civilisation, and another series on the history of Indian cinema.

“His art, especially the large amount of work he did in his 90s while in exile, stands as an indictment to the shortfall of Indian democracy,” says Bruce Lawrence. “Ironically, Maqbool could not be stopped, or stunted, by the demagogues and thugs who attacked at home.”

As one of his final projects before he left India in 2006, Hussain took on the designing of the store for a shoe-maker friend at Mumbai’s Taj Mahal Hotel. From the shelves to the ceiling to the furniture he obsessively planned everything. At the entrance of the store, Hussain’s bare feet are cast in bronze.

He died in exile, but the marks of his bare feet and long brush remain across India – and museums around the globe.

Follow Mujib Mashal on Twitter: @mujibmashal