Inside Deraa

The story of this ancient town is the story of the Syrian uprising: state brutality, funerals and growing fury.

|

| The uprising that spread all over Syria was sparked in the ancient town of Deraa [REUTERS] |

The only outside visitors the people of Deraa are allowed to receive these days are friends and family attending funerals.

To access the city where Syria’s uprising began a local reporter simply had to tell the guards at the first checkpoint the truth: The husband of his wife’s cousin had been killed while protesting for freedom and he was there to help bury him.

At three more checkpoints on the road into the city, security men scoured the car for cameras, recorders or laptops, anything that could be used to document the death and destruction that has been wrought on this ancient and increasingly arid farming town on the border with Jordan.

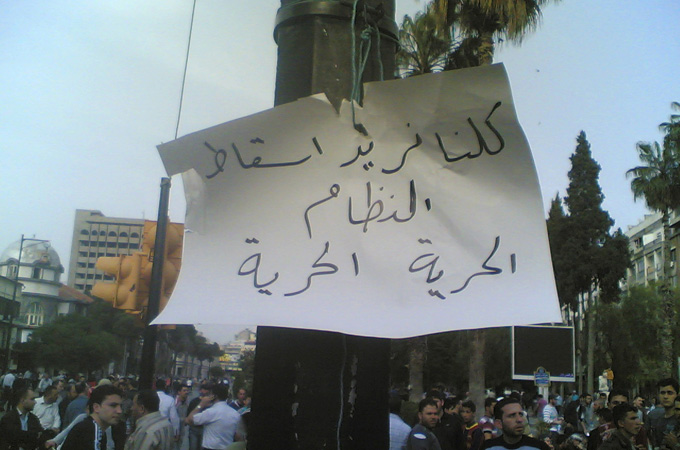

It was here on March 6 that the spark that lit the Syrian uprising was struck: The arrest, detention and torture of 15 young boys for painting graffiti slogans of the Arab revolution – “As-Shaab / Yoreed / Eskaat el nizam!” “The people / want / to topple the regime!” on a wall, copying what they had seen on television news reports from Cairo and Tunis.

The boys, aged between 10 and 15, were taken to one of the cells of the local Political Security branch, under the control of General Atef Najeeb, a cousin of President Bashar al-Assad.

There in the gloomy interrogation room the children were beaten and bloodied, burned and had their fingernails pulled out by grown men working for a regime whose unchecked brutality appears increasingly to be sowing the seeds of its undoing.

Human Rights Watch recently documented multiple cases of torture, including of children, among hundreds of cases of protesters arrested over the past month.

The story of Deraa is the story of the Syrian uprising: A single incident of brutality by a lawless secret police that ignited protests, which in turn escalated in size and scope fuelled by the ever increasing numbers of people killed by security forces.

Family blood

The disappearance of Syrian citizens, even children, inside the cells of one the state’s notorious security branches might not have ordinarily been anything unusual for a people accustomed to living for half a century under emergency laws.

But the arrested boys were from almost every large family of Deraa: The Baiazids, the Gawabras, the Masalmas and the Zoubis.

In the largely tribal society of Syria’s south, family loyalty and honour run deep. So, after days of failing to locate the boys through official channels, the parents and families of the missing, along with local religious leaders, marched on the house of the Deraa governor Faisal Kalthoum after Friday prayers.

READ MORE: Syria’s Civil War Explained

The governor’s security guards initially struggled to beat the protesters back before riot police were called in and used water canons and tear gas. Then armed members of Political Security turned up and opened fire on the protesters.

“A large number of security arrived and started shooting at people and injured some of them,” said Ibrahim, a relation of one of the arrested boys.

“When the people saw the blood, they went crazy. We all belong to tribes and big families and for us blood is a very, very serious issue.”

The gathering, which had started out with around 200 people, quickly swelled to several hundred as news spread around Deraa that Political Security had opened fire.

“We were asking in a peaceful way to release the children but their reply to us was bullets,” said Ibrahim.

“Now we can have no compromise with any security branches.”

Another relative of one of the children said he had witnessed the contempt with which General Najeeb of Political Security had treated the family delegation.

“Security prevented the ambulances from coming to take injured people to the hospital. We will not forget that,” said Mohammed, a 28-year-old who moved back to Daraa two years ago after working in Dubai.

Since protests erupted in Deraa, Mohammed’s brother-in-law has been killed and his brother injured.

There were also unconfirmed reports that General Najeeb had taunted family members, telling them to forget about their children and go home and sleep with their wives to make some more.

Prevented from reaching hospital, the enraged protesters took the injured to the Omari Mosque in the heart of Old Deraa.

Mosque stormed

On March 18, several hundred protesters in Deraa called for an end to corruption, the release of the boys and greater political freedom. Security forces opened fire and killed three. Two days later, furious crowds set fire to the offices of the Baath Party, calling for the first time for freedom and an end to emergency law.

Al-Assad attempted to defuse local anger by sending a delegation of high-ranking officials with family ties to Deraa to reassure tribal leaders that he was personally committed to bringing to justice those who had opened fire.

The delegation included Faisal Meqdad, the deputy foreign minister, whose former boss, Farouk al-Sharaa, now vice-president, is also from the region.

But the delegation’s most important figure was General Rustom Ghazali, one of the highest ranking members of Syria’s Military Intelligence, who was head of Syrian intelligence in Lebanon when prime minister Rafiq al-Hariri was assassinated, and who faced questions in the subsequent international investigation into the murder.

As a man from the area and a senior member of al-Assad’s inner circle, Ghazali was there to give assurances to Deraa leaders that the situation could be calmed down.

In a gesture of goodwill the 15 children were released, having spent two weeks in jail.

But the marks of torture on their sons only fuelled the rage of local tribal leaders. Now the demonstrators against the regime numbered in their thousands.

In the early hours of the morning of March 23, just 48 hours after Ghazali’s meeting in Deraa, Syrian security forces stormed the Omari mosque, which had become a focus for the growing protest movement. Troops threw in stun grenades before opening fire, killing five people, including a doctor who was working to treat those injured in previous protests.

Footage on YouTube claiming to show the aftermath of that raid shows plain clothes gun men parading around inside a mosque with blankets lining its walls and blood stains visible.

Locals said the men who actually stormed the mosque were Syrian special forces, with unconfirmed reports that they belonged to the army’s fourth division, under the command of Maher al-Assad, the president’s brother.

“We want the president to punish all of those who killed and injured the people of Deraa,” said Mohammed’s mother, an Arabic-language teacher, visibly shaken with sorrow and anger.

“We supported his father [Hafez al-Assad] and he appreciated us by nominating a Zoubi as prime minister, Sharaa as foreign minister and Suleiman Qaddah as the Baath Party’s leader. But instead, President Bashar sent our own sons, the Syrian army, to kill their brothers and sisters. A traitor is the one who kills his brothers.”

The following day, the much reviled Governor Kalthoum, whose residence was burned down, was sacked. General Najib was also removed from his position. Over a fortnight later, al-Assad referred the two men to court to investigate their role in igniting and handling protests in the city.

But the sackings did little to abate the anger of locals.

“Why didn’t President Assad visit Daraa himself and say sorry to the people,” said Mohammed. “We are 100 per cent Syrian and he should show us real sympathy and respect.”

Funeral protests

The Deraa protests began to grow exponentially, falling into a familiar and tragic pattern: The funeral for those killed a day earlier would swell into a mass rally against the regime and security would open fire, killing more and guaranteeing an even larger turnout at the next funeral.

On March 24, the government issued a decree to cut taxes and raise state salaries by 1,500 Syrian pounds ($32.60) a month.

A day later tens of thousands turned out for funerals in Deraa shouting: “We do not want your bread, we want dignity.” Security opened fire and killed 15.

A group of enraged protestors tore down the statue of Hafez al-Assad, the former president, whose name most Syrians hardly dared whisper, such was the fear he once inspired. Pictures of Hafez’s son, Bashar, were ripped and burned.

In one week of protests in and around Deraa at least 55 people had been killed by security forces. Across the country the pledge to Deraa became a unifying chant of the protest movement: “With our souls, with our blood, we sacrifice to you Deraa.”

‘Foreign plot’

In his first public statement on the crisis, al-Assad blamed the uprising on a “foreign plot” and said those killed in Deraa had died as a sacrifice for national stability. The speech only fuelled the anger of families like Mohammed’s.

“He didn’t ask the MPs to stand for a minute’s silence and he said those who were killed were sacrificial martyrs,” said Mohammed. “But here in Deraa, the army and security deal with us like traitors or agents for Israel. We hoped our army would fight and liberate the occupied Golan, not send tanks and helicopters to fight civilians.”

By April 8, the fourth consecutive Friday of protests, the chants on the streets of Deraa were pure fury. “Hey Maher you coward, take your dogs to the Golan,” shouted the protesters, 25 of whom were killed on that one day.

One week later, a delegation from Deraa held their first direct talks with the president. But for many residents of a city that once prided itself on sending its sons to top positions in government the surprising transformation of Daraa into the centre of Syria’s uprising is unlikely to be easily reversed.

“They think we want new roads or a new hospital. No! We want to lift the state of emergency, release all political prisoners and allow our relatives who live in Jordan, Saudi Arabia and other countries to return to Syria. We want to buy and sell our land without permission from security,” said Ayman, an opposition activist from Deraa.

“My uncle is suspected of being a member of the Muslim Brotherhood and so was forced to live in Saudi Arabia. Every day my grandmother prayed to God that she could see her son, but she died without ever seeing him again. What we want now is freedom.”