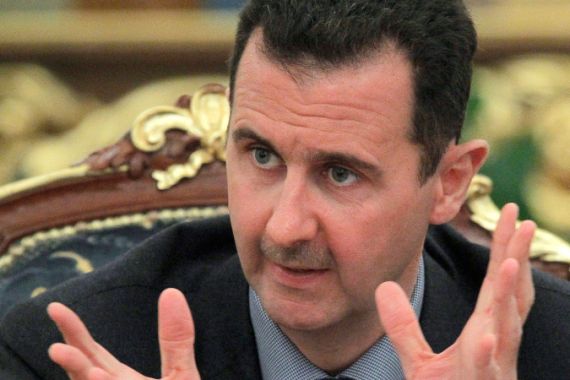

Syria: Simmering unrest a worry for Assad

The Syrian president insists his country is different, but it shares some economic problems with its neighbours.

Drought is a growing economic problem in Syria, despite a number of new government irrigation projects [EPA]

Drought is a growing economic problem in Syria, despite a number of new government irrigation projects [EPA]The Syrian government is struggling to contain a week-old uprising in the southern city of Deraa, the deepest popular unrest since president Bashar al-Assad took office a decade ago.

It is not the first political rumbling in Syria this year: Several small protests took place across the country last month, including a demonstration against police brutality in Damascus, the capital, which ended when the interior minister showed up and promised to punish the offending officers.

But it is the Deraa protests which bear the most resemblance to the rallies that have swept Arab countries since December. Protesters have chanted “God, Syria and freedom,” and “the people demand the downfall of corruption,” the latter a variant on the familiar slogan (“the people demand the downfall of the regime”) which has become the standard of this year’s Arab revolts.

Syrian officials, clearly unnerved, have flown thousands of security forces into the city and brutally cracked down on demonstrators. They have blamed the protests on foreign powers, accusing organisers of stockpiling smuggled weapons from Israel.

Concessions and crackdowns

Popular protests have been slow to kick off in Syria, where many have bitter memories of former president Hafez al-Assad’s brutal repression of opposition groups in Hama. Assad dispatched elite army units to quell that uprising in 1982; tens of thousands of people were massacred, and much of the city was demolished by tanks and aerial bombardment.

The younger Assad has taken something of a middle path in Deraa. He has deployed thousands of security forces to the city, with lethal effect: at least ten people have been killed since protests began, in addition to many others wounded or arrested.

At the same time, though, he has made a few conciliatory gestures to protesters, like releasing the children whose arrests – they were detained for writing pro-democracy graffiti – helped spark the protests, and sending a delegation of government ministers to meet with protesters.

So a key question, it seems, is whether he can contain the protests in Deraa. They have not spread widely outside of the city, save for scattered (and small) demonstrations in Damascus, Homs and Banias. Syria’s restive Kurdish minority has shown little interest in joining the fray.

The protesters in Deraa have chanted pro-democracy slogans, but they also have more localised grievances: farmers are struggling with water shortages, and the city is straining to cope with an influx of migrants from dried-up agricultural towns in eastern Syria. The city’s leaders have also demanded the sacking of the governor and the local security chief.

Ameliorating those grievances could buy the Syrian government a reprieve from protests.

Layers of insulation

Assad likes to insist that Syria is different than its neighbours. As he told the Wall Street Journal in January, “we are not Tunisians and we are not Egyptians.”

It is a true enough statement: there are notable differences between Syria and its Arab neighbours, many of which tilt in the regime’s favour. It is a predominantly Sunni country ruled by an Alawite minority, for example, a dynamic which gives Assad an extremely loyal power base in the government and military.

Perhaps the most notable difference is Assad’s foreign policy, which has (to an extent) insulated him from popular protest. Foreign policy has been a common theme of several Arab uprisings: In Egypt, for example, it was common to hear slogans criticising former president Hosni Mubarak’s relations with the United States and Israel.

Assad’s foreign policy shields him from some of the criticism directed at the leaders of neighbouring states [EPA]

Assad’s foreign policy shields him from some of the criticism directed at the leaders of neighbouring states [EPA]Assad has made overtures towards Israel, but always insists on the return of the Golan Heights as a precondition for talks; while the Syrian-Israeli border has remained quiet on his watch, he continues to support Hezbollah; and he has refused to align himself too closely with the US or Europe. All of these policies have proved fairly popular at home.

Tensions with the West also give Assad a useful foil for Syria’s economic troubles, which he can attribute to the effects of international sanctions.

Assad alluded to this in his Wall Street Journal interview, when he mentioned a friend whose medical lab is unable to import equipment from the United States because of sanctions.

“That influences the life of the people if you don’t have the right calibrator for lab analysis, for example,” Assad said. “This means that you are giving wrong results to people. You diagnose somebody with cancer while he doesn’t have cancer. What did the people do to the United States to deserve this?”

A microeconomic gap

Assad told the newspaper that he expected to sustain 5 per cent annual economic growth rates for the next five years. But despite the cheerful proclamations from Damascus, the Syrian economy is undoubtedly troubled on a micro level: the unemployment rate is between 12 and 20 per cent, depending on who you ask, and 14 per cent of the population lives below the official poverty line.

Youth underemployment is a particular problem; it’s not uncommon to find taxi drivers with advanced degrees in Damascus or Aleppo.

And there is perhaps growing frustration with the divide between rich and poor: At one rally, there were chants of “down with Makhlouf” – a reference to Rami Makhlouf, the president’s first cousin and a businessman who controls billions of dollars of Syria’s economy.

Makhlouf’s riches are endemic of the corruption within Syria’s ruling elite, a growing point of frustration for many in the country. His connections earned him lucrative deals for oil exploration and power plants, and give him virtual veto power over foreign firms seeking to do business in Syria.

Syria does not have quite the same grinding poverty that’s on display in, say, the slums of Cairo, but officials are clearly worried that a worsening economy will lead to political unrest. The government unveiled a new unemployment aid fund last month, and Syrian officials acknowledged that they sped up its launch in response to the uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia.

In an editorial “on change or reform in Syria,” Ibrahim al-Amin, the editor of Lebanon’s influential Al-Akhbar newspaper, argued that future economic reforms in Syria would be inevitable.

“What happened and is happening in the Arab states proves the impossibility of keeping things as-is in Syria, or in any other Arab country, when it comes to the level of freedom or to economic policies,” he wrote.

Follow Gregg Carlstrom on Twitter: @glcarlstrom