The tides of mosques

Protesters were hoping Ramadan would prove a turning point, yet the powerful regime managed to quash most dissent.

|

| The Syrian government has responded to peaceful protests by deploying military forces [Reuters] |

This is the final instalment of a three-part feature by Al Jazeera journalist Nir Rosen. For the previous chapters, click here: Ghosts in the mosques [part one], Syria’s symphony of scorn [part two].

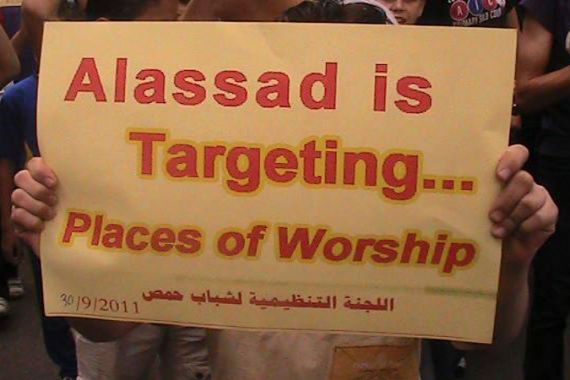

Syrian protesters have been denied access to public spaces, such as the squares that have become famous in Yemen and Egypt. This has led to mosques playing an even greater role than they already would have.

With the number of dead from the uprising reaching possibly five thousand, funerals have also provided an opportunity for communities to gather and express their ire.

Funerals are a convenient place to express opposition to the regime because attendance in a funeral does not imply active opposition, and mourners are protected by the crowds. One of the few times a portrait of President Bashar was destroyed in Aleppo was during the funeral of Mufit Ibrahim al-Salqini. Often Saturday funerals have had greater crowds than the Friday demonstrations that preceded them. And while security forces have certainly shot at protesters during funerals they have been more reluctant to do so.

On August 19, a friend named Abu Salah drove me to a daytime funeral and demonstration in the eastern Homs slum of Bab Assiba.

Abu Salah was a businessman who lived in the western neighbourhood of Waer and helped the opposition. He drove a car with fake license plates and delivered aid from wealthy areas such as Ghota, Inshaat and Hamra to the poorer neighbourhoods across town – such as Bab Assiba. We stopped to pick up a friend of his, a man with a beard but no moustache, a sign of conservatism.

As we drove, he received a call letting him know that his cousin, Nawar Nawriz, had died from injuries received the previous night – when attackers had shot at the Fatima mosque while he was praying. After being wounded he was taken to a “field hospital” – a safe house used as a clinic.

Abu Salah told me that opposition supporters donated blood themselves, but they lacked the packs to hold the blood and they needed morphine and medicine to prevent infections and to meet medical needs.

We continued to driving to the Muhata area and passed the Military Security department. A white Peugeot station wagon was parked on the road leading to it, inside and outside the car sat men with rifles.

We entered the Karm Ashami district, passing the Bisman security checkpoint. Abu Salah told me it was known as a very cruel checkpoint because it was between a Sunni area and the Alawite areas of Hadara and Akrama. We entered Bab Hud and continued through Bab Turkman and on to Safsafi. The narrow and rough streets had old houses made of large stones. Many shops and buildings were damaged by automatic weapon fire, including large gashes from heavy calibre rounds.

We left the car parked in the Zaafaran neighbourhood, and walked through alleys pocked with bullet holes, crossing the main road to Bab Assiba.

Every wall, from top to bottom, was ravaged with bullet holes from seemingly every angle. There had been fierce battles here between Syrian security forces and armed opposition fighters. Down the road, at its entrance, was a tank by the checkpoint we bypassed by walking in. Parts of the barrier on the road between the two neighbourhoods had been broken to make space for cars to sneak through at night. Most of the shops in Bab Assiba were closed. There were old signs on the walls calling for a general strike.

We walked to the Mreiji mosque where a large crowd was gathering, waiting. The mosque was full of mourners praying. I asked Abu Salah if people would be concerned that we were strangers. He told me not to worry; if anybody stopped him, there were code words he could use that would reassure them.

Men emerged from the mosque shouting “God is great!” over and over, led by one man, sitting on someone’s shoulders, holding a loudspeaker. The crowds carried a stretcher with a body wrapped in white cloth, with the head exposed. He had been killed the previous night in the mosque when a bullet allegedly ricocheted off a wall in the mosque, hitting the back of his head and coming out of his eye.

His body was followed by that of an eight-month-old girl. Locals told me she was the daughter of the mosque’s sheikh, Anas. The procession marched down a road taking both to the newly named “Martyrs Cemetery”.

The mosque’s walls and windows were riddled with bullet holes. Many of the young men standing outside looked hardened and tough, even thuggish. I stuck close to my local guides. Many men had beards, but shaved their moustaches – a sign that they were religiously conservative.

When it was over, we crossed the road back in to Zaafaran. Its Saad ibn Ali Waqas mosque was also full of bullet holes. As we departed, my friend said to himself: “Rise, oh Assi River, rise. Every day we have a martyr.” It was an opposition slogan that rhymes in Arabic, referring to the symbolic Assi River that runs through Homs. Three days later my friend would be arrested after a demonstration in Homs’ Clock Square.

|

| Opposition is widespread in Syria, young girls even take part; the text reads: ‘freedom peacefully’ [Reuters] |

Rent-a-thugs

While most of the population of Homs appears to support the uprising, Syria’s largest city, Aleppo, has remained docile, frustrating many in the opposition. The morning of the following Friday, I drove north to this wealthy majority Sunni city.

The road to Aleppo was mostly empty; in anticipation of demonstrations, the city was blocked with two checkpoints staffed by security men in civilian clothes, rifles slung over their shoulders. They turned many cars away.

“Aleppo is closed today,” a security officer told one driver, “Come back tomorrow.” Some businessmen managed to beg their way past the checkpoint.

We approached the checkpoint, and when the guard saw my US passport, he asked me why we were “making war” on them. All I could do was smile apologetically. Between me calling a friend who had good connections and them not being able to find a legitimate reason to turn me away, they let me through, and so we continued on to Aleppo.

Once there, I met two young activists who took me to one of the poorer neighbourhoods called Sakhur. Aleppo’s first martyr from regime gunfire was killed in Sakhur a week earlier. Its people were known for being tougher, more defiant, and also more violent; they resisted the security forces, and in fact recently killed a few.

Sakhur, Salahedin and Seif Addawleh were the city’s three opposition strongholds. On the road between Shaar roundabout and the airport bridge, there were about a hundred security men in the Bab Allah park, which was just across from the Abu Bakr mosque. There were maybe ten security men standing in front of the mosque, equipped with clubs, teargas and shotguns.

|

“Damn your soul, Hafez!“ – Syrian protesters |

Further down the hill were security men with rifles, and at the bottom of the road, next to the Gaza school, were four men wearing body armour and carrying rifles.

About five hundred men sat in the mosque listening to a somniferous sermon about Ramadan which avoided anything political. After the sermon and the prayers, there was a resounding silence. Unlike other mosques I had been to nobody, called out “God is great!” to mark the start of the demonstration. Instead the men shuffled out without a word under the gaze of the security men. One man murmured “pray for the Prophet,” and one man quietly responded “Our God prays on the prophet Muhammad”.

Several hundred youth walked up the hill to gather. They pulled out banners and flags, and began to call out the standard anti-regime refrains: “The people want the downfall of the regime!” and “Damn your soul, Hafez!”

They marched towards the mosque, performed an about face, and walked back down the hill, turning a corner. Dozens of state security forces followed them. Men from the neighbourhood stood idly by, leaning against the walls, watching. Shop owners hastily shuttered their shops.

Security forces closed off the entire neighbourhood, bringing in buses full of armed men. That day, Sakhur was the only neighbourhood in the city that had held a protest after the Friday prayers.

Demonstrators in Aleppo had hoped to establish a sit-in at the central Saadillah al Jabri Square next to a park – now full of security officers – but local regime supporters had attacked them in the past. Attempted demonstrations in the university had also been suppressed and student activists punished.

That night I went with two activists to the Qutaiba mosque in the wealthy area of Suq Mahalia. Two different groups of opposition coordinators had agreed to stage a demonstration there that night. When we drove by, we saw at least thirty thuggish men standing in front of the mosque. They wore civilian clothes, some with impressive gullets and many were bearded. They were older than most security men. Some had clubs stuffed into their shirts, behind their backs. These men were known as shabiha – civilian thugs hired by regime supporters and assisted by the security forces. Other shabiha loitered on the side streets in groups. They wore shabby dark clothes and did not belong in the neighbourhood. Not far away was the bus that had brought them there. It had a large picture of Bashar al-Assad on it.

Young demonstrators cautiously approached the street leading to the mosque. They wore trendy clothing and looked like students. They did not have the tough look I had seen in other demonstrators.

They spoke in codes about demonstrations, often referring to them as football matches – for instance, they might call their friends to ask, “Which field are you at?” When they saw security, they called their friends and said “There are lots of players from the other team here,” or “the referee is here,” or “it’s very dirty there”.

When they saw the shabiha that night, they turned away and the protest was cancelled. Somehow security men always seemed to know in advance.

“It’s busted,” one of the activists with me said.

A cautious delegation

A United Nations delegation, tasked with assessing whether there was a humanitarian crisis in Syria, visited Homs on August 22. They met with the governor, and even though they were accompanied by an escort from the ministry of foreign affairs, they were granted permission to visit anywhere they wanted; the escort did not even object, much to their surprise. But the foreign ministry did insist that no filming was allowed.

|

“One, one, one, the Syrian people are one“ – Najati Tayyara, leftist Alawite speaker |

Demonstrators and opposition activists were desperate to get their attention, so they staged a protest in Clock Square. The last time they did that was in April, in an attempt to replicate Egypt’s Tahrir Square.

In that sit-in, the leftist Alawite speaker Najati Tayyara was welcomed with cheers of “one, one, one, the Syrian people are one!” At about one in the morning, security forces attacked the demonstrators with live fire, killing some.

Protesters carried signs that read “SOS”. They had leaflets in English, and pleaded with members of the UN mission. “They will slaughter us after you leave,” implored one man.

The overly cautious UN security advisers warned members of the delegation that if they even opened their windows a little bit to receive a piece of paper, they would be expelled from the rest of the mission.

When they realised they could not talk to the delegation, demonstrators grew more aggressive, though not threatening. Some laid down in front of the UN vehicles.

The UN mission, without a guide, did not know where to go, and decided to call the governor’s office for assistance. Security forces arrived with clubs to disperse the protesters, who replied with stones, some of which accidentally landed on UN vehicles.

“They turned savage on us,” said an opposition leader who was present, in reference to the security forces. “Clock Square is a red line for them so security came and shot at us. First they shot into the air. It hit the glass and the walls. We stayed so they stayed. Then the Khalid bin al Walid Brigade came and shot at them.”

The Khalid bin al Walid Brigade was a Homs-based unit of defectors from the Syrian army, who had joined the opposition and conducted operations to defend demonstrations as well as to attack security forces. Several protesters were killed by security forces, and in turn at least two of them were killed by armed opposition members. One policeman was shot, and a colonel in the army named Ali Nidal Hassan was killed, allegedly by an opposition sniper.

“Ali Hassan died because of the UN delegation,” his boss said. He had been assigned to secure the area around the UN delegation because security had intercepted phone calls discussing a planned operation in the area.

That night, my friend Suheib took me to Midan in Damascus. Its status as a rebellious neighbourhood went back to the 1920s when residents rioted against the French. Through the 1960s to the 1980s, it was a hotbed of conservative opposition to the Baath party.

Since the latest uprising, security and armed thugs were posted in various parts of the neighbourhood. We drove through very dark streets looking for mosques. We heard one shot fired and saw a commotion down the street not far from the Ghazwat Badr mosque.

Men hastily told the children on the street to find somewhere safe to hide. One man, Khalil, was standing outside his building waving kids in. Security forces grabbed him, accusing him of helping protesters. He was forced into a station wagon as his young son cried and screamed desperately. Locals watched helplessly. Others restrained his son, consoling him.

Two security men with pistols stood in front of the station wagon and waved people away. Minutes later, two electricians showed up looking for Khalil. He had been waiting on the street corner for them as they had agreed so they could repair something.

I strolled by and watched from the door of a grocery store. Suddenly, a teenager no older than 15 sprinted by me shouting in terror as two security men in sloppy green uniforms holding truncheons chased after him. They were followed by at least ten other security men, who laughed as they jogged; it seemed fun for them. They were older, in their 40s, and overweight. Soon, others followed. At least one carried a rifle and another one carried a tear gas launcher.

I bought a drink from the grocery store and went back outside, continuing to observe the events as they unfolded. Moments later, dozens of security forces marched by me. A riot control policeman with a helmet, shield and a club marched towards me. I tried to force a smile and wave. He marched right past me.

The men of the neighbourhood could do nothing but watch the grim procession. Some gathered afterwards to discuss what they saw and what might happen to Khalil.

“He’s never coming back,” said one man.

|

| The flag is an important symbol for the Syrian protesters who are in opposition to Bashar al-Assad’s state [Reuters] |

A tough crowd

The next night, Suheib picked me up again. He told me that the day before, he had seen nine buses full of security entering the suburb of Kisweh. That night, we drove to Harasta.

We came upon a traffic jam, the cause of which was a checkpoint, holding up cars and searching them. Plain clothed security officers – armed with pistols – sat on a corner, drinking tea. Uniformed men strapped with rifles were stopping cars and checking IDs.

Suheib circumvented them, taking a different route through narrow side roads on the perimeter of the area. We were confronted with another checkpoint leading to Zamalka. I turned up the Western pop music on the radio. I was dressed formally to reduce suspicion. As I started to pull out my identification, the soldier just waved us by instead. We must have looked harmless enough.

The main street in Zamalka seemed normal. People were out shopping. At 10pm that night, we drove through crowded Arbeen. Its main market street was overflowing with shoppers, especially women and children, forcing us to drive slowly. As we waited for the crowds to part, I noticed how conservative the area was. All the women wore the hijab. Most only revealed their eyes. Others wore a burqa, concealing their faces entirely.

We continued on to Harasta. Some shops were closed and there were fewer people out, but there was no demonstration.

|

“One of the men, Abu Ibrahim, stopped two colleagues seated on a motorcycle and asked them for their opinion.“ |

As we looked for a way out of town, the streets grew darker, unlit and emptier. The narrow street we wanted to pass through was blocked by a couple of stern young men. One, bearded with angular features, told us it was closed and waved us in a different direction. Suheib insisted we had to go through, so he let us pass.

We passed the Sheikh Musa mosque. On the other side there was another makeshift checkpoint. Informal local security blocked the street. They were older, in their 30s or 40s. Some sat on motorcycles. They were bearded and tough-looking. Suheib parked the taxi, and we walked to the mosque.

A few hundred men emerged and demonstrated for about ten minutes. We stood on the perimeter and watched. I felt uncomfortable as a stranger. The local men conducting security stared at me, recognising that I was an outsider. This prompted me to suggest leaving.

Suheib adroitly approached some of the older local toughs providing security for the protest and asked them how we could leave Harasta safely, avoiding checkpoints. One of the men, Abu Ibrahim, stopped two colleagues seated on a motorcycle and asked them for their opinion. The one seated up front was a large, thick, bearded man. The man behind him was short and wiry, also sporting a beard.

My friend introduced me to them, and had a brief conversation with them. They explained that the demonstration behind us was composed of men from several mosques who joined together. As we spoke we heard a loud bang.

“Go see,” Abu Ibrahim told the man on the motorcycle, who spun around and sped away.

Abu Ibrahim showed me the shotgun pellets still embedded in his face and body from when a civilian security man shot at him from out of a car. The two men on the motorcycle led us out. Before crossing into Arbeen they told us to wait. They drove ahead to look for checkpoints.

They told me they coordinated with the guys from Arbeen and Zamalka as well to monitor the movements of security forces. They returned and said it was safe for us to go. We drove through Arbeen to Zamalka and back into central Damascus.

Not quite the Golan

The next Friday, August 26, was of particular significance, because it was the last one of Ramadan. In occupied Palestine, Israeli security forces took extra measures against Palestinians in anticipation of demonstrations, and in Syria security forces did likewise, suspecting further gatherings.

The Syrian opposition named that day “Friday of patience and persistence”. In the Omar Mosque of Homs, Sheikh Mahmud al Dalati told his followers that victory would surely be coming. He praised the people’s unity. He said he never imagined that he would see people from Ghota, Inshaat or Hamra, wealthy areas, crying and carrying on their shoulders the body of a man from Khaldiyeh, a poor area. People had also become more religious, he said, reading the Quran for the first time, or reading it several times when they had never read it before. A demonstration followed as usual. “Israel, Assad is with you to death!” people shouted, mocking their president.

In advance of the noon prayers and the anticipated demonstration, the head of state security in the Damascus suburb of Duma, Lieutenant Colonel Samer Breidi, gathered some 300 men from state security and riot control police with shields and clubs for a briefing. Dozens of them brought their AK47s. Breidi lost his temper when he saw this.

“What do you think, you’re going to liberate the Golan?” he shouted at them, cursing at them as he angrily hit and kicked his men.

He ordered that only eight men would be allowed to carry rifles with live rounds, and they would be the guards on the buses

|

“A security friend told me to stay in that night because they were expecting a lot of trouble, and the regime response would be harsh.“ – Nir Rosen, journalist |

transporting the other men. They were ordered to remain on the buses with their rifles. Ten men were assigned to carry shotguns with rubber bullets. Three men were assigned to carry tear gas launchers. The rest could only carry truncheons.

Ali Mamluk, the Sunni head of State Security, wanted to avoid killings, said someone who worked closely with him. Other security agencies were less disciplined and more likely to lose control. Samer Breidi was known as a man less prone to violence. He would get on the phone and beg Military Security generals not to intervene, promising that he could take care of the situation.

That Friday, protesters burned two garbage dumpsters and several tyres. The fires were put out with water cannons. Security forces fired tear gas at the demonstrators. Military security was attacked with small dynamite sticks, sound bombs and Molotov cocktails. Two members of military security were shot, as were at least three protesters.

At the same time, according to State Security, Sheikh Osama Rifai of the Rifai mosque in Damascus’ Kafar Susah, asked in his Friday sermon that women not attend the night time tarawih prayers later that day. Early the next morning, clashes would take place inside and outside mosques, which would give the opposition a fillip, and provoke rage at the violation of a mosque and assault on a leading cleric known to be anti-regime.

That night I was back in Homs. I had been warned by friends in the opposition and security forces to be careful and to expect clashes. A friend in the opposition showed me how to approach the protests by the Omar mosque while avoiding places where there might be checkpoints.

A security friend told me to stay in that night because they were expecting a lot of trouble, and the regime response would be harsh. I took the back streets to the mosque, but there was no sign of security. The main street was full of teenagers preparing for the protest. They blocked off the entrance to the street as usual with bricks and garbage dumpsters.

Many teenagers stood outside the mosque waiting for the demonstration to begin. About twenty women joined the demonstration on its fringes, shouting: “The people want the downfall of the regime.”

But no security forces came that night.

Turmoil at the mosques

Early the next morning in Damascus, clashes erupted outside the Rifai mosque in Kafar Susah. An opposition friend of mine was present in the demonstration but could not say exactly what happened.

He told me that at about 3:30am, after the tajahud prayer, men emerged from the mosque shouting “God is great” and other chants on the way home. They were shot at with plastic or rubber-coated rounds from close range. Other men inside the mosque, and barricaded it to protect the sheikh after a rumour spread that security officials were coming to arrest him. After some negotiation, people started to leave. But then the shouting and shooting resumed, and the sheikh was injured.

According to state security, clashes broke out in the mosque’s rear entrance after a demonstrator broke a bottle from breakfast (being served inside the mosque), and stabbed a security officer in the neck.

“Then security forces went crazy,” my security source said.

State and military security shot people with rubber-coated bullets and only outside the mosque, he told me. The man who attacked the security force member fled inside the mosque. Inside, people barricaded themselves and refused to hand him over.

|

“Protesters also mocked Bashar al-Assad and state Mufti Hassun, while praising the incendiary exiled Sheikh Adnan al Arur. “ – Nir Rosen, journalist |

Demonstrators threw stones, bricks and bottles from inside the mosque at the security forces, he told me. Eventually security forces were able to capture the man. During the raid on the mosque, one angry security member hit the sheikh on the head with a club.

The man who allegedly stabbed the security officer with a broken bottle was captured. Beneath an apartment building they beat him so violently and for so long that my source in security expected he would not survive.

This was not the first time that the mosque had been besieged by security and thugs, however. Even in March, security forces would beat protesters coming out of the mosque. That said, chances are that if someone from state security was indeed killed, it was likely by protesters who were already under attack, activists told me.

That night I attended the demonstration in Homs’ Old Waer district. The location had been moved away from the fire department to the lot outside the Rawda mosque, as the fire station was now occupied by soldiers and security officers. Women and old men had joined the demonstration. “Down down with the regime and down with the Baath party!” they said. Protesters also mocked Bashar al-Assad and state Mufti Hassun, while praising the incendiary exiled Sheikh Adnan al Arur.

Two wounded protesters were brought into the nearby Birr hospital. One man was from Khaldiyeh and had been shot three times near to the Abbas mosque. The other man was shot in the side of his neck and his ear in the Jurt Ashiyah neighbourhood. A doctor treating them at the hospital was angry at the activists for not coming in to film the two wounded men.

Elsewhere in the city, a man named Bassim Khazandar was killed, while another was injured by what activists described as a nail bomb. At the hospital, we got word that a Red Crescent ambulance that had just left was stopped by security, who then took it over and drove away with it. The activists I was with hurried away.

No end in sight

I went to Bab Omar the following night with a friend. His eight-year-old son whispered shyly in his ear, asking him if he could come with us to the protest.

|

“It’s written on our flag – Bashar is a traitor to the nation!“ – Syrian protesters |

The opposition had hoped Ramadan would be a turning point, but it was soon coming to an end. Contrary to their hopes, the Syrian regime had succeeded in limiting protests, and it was the Libyans who were celebrating, thanks to international military intervention. The opposition was slowly beginning to believe that, without an armed rebellion or international military support, they may never overthrow the powerful regime.

Thousands gathered in Bab Omar for the demonstration. They changed the words of a song called “Where are the millions,” by the Arab nationalist pop star Julia Boutros. “Where, where, where are the millions,” they sang, “Millions of Arabs? Where are Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the Emirates? Where is the no fly zone? See what happened in Kafar Susah?”

As I watched them, I remembered how regime supporters described protesters as Islamic extremists. “Look, a terrorist!” a local guide pointed at a young demonstrator and smiled as he mocked regime propaganda. The men danced in a circle while one demonstrator played a drum. They sent salutations to Al Jazeera, Al Arabiya and Sheikh Adnan al Arur. They damned the Syrian media. They burned a picture of Bashar al-Assad.

“The people want the execution of the president!” they shouted. “The people want a no-fly zone!”

“It’s written on our flag – Bashar is a traitor to the nation!”

One man with a microphone pretended to be al-Assad, and offered the demonstrators whatever they wanted in order to placate them.

He then asked them what they wanted. In thunderous unison, he got his answer: “Go!”

You can follow Nir Rosen on Twitter @nirrosen