China: A force for peace in Sudan?

Beijing has invested billions in the oil-rich country and may now have to step up to ensure stability prevails.

|

| While southern leaders want political independence from the north, economic realities may keep them tied to the north[Reuters] |

As the world anxiously watches the southern Sudanese vote on whether to secede, one country has more to lose than most if civil war returns to Sudan.

With an estimated 24,000 of its citizens living there and billions of dollars worth of investments in the country, China is the key foreign player in Khartoum.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWhat’s slowing down America’s clean energy transition? It’s not the cost

Global coal use to reach record high in 2023, energy agency says

COP28 Dubai is over: Four key highlights from the UN climate summit

When the US oil giant Chevron pulled out of Sudan – beginning in 1984 when three of its employees were killed and culminating in 1992 when it finally sold all of its Sudanese interests – the state-owned China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) stepped in.

It now has controlling stakes in the biggest energy consortiums operating in Sudan, giving China an estimated 60 per cent share of the 490,000 barrels of crude oil produced daily.

It also constructed the 1,500km pipeline that connects the oil fields of the south with Port Sudan in the north – from where the oil is exported.

But with oil accounting for more than 90 per cent of government revenues in the south, compared to just over 40 per cent in the north, there is a possibility that Khartoum could close the pipeline should the south vote for independence.

This decision would not only be devastating for the underdeveloped and oil revenue-dependent south, but would also disrupt China’s oil supply.

Friends in the south

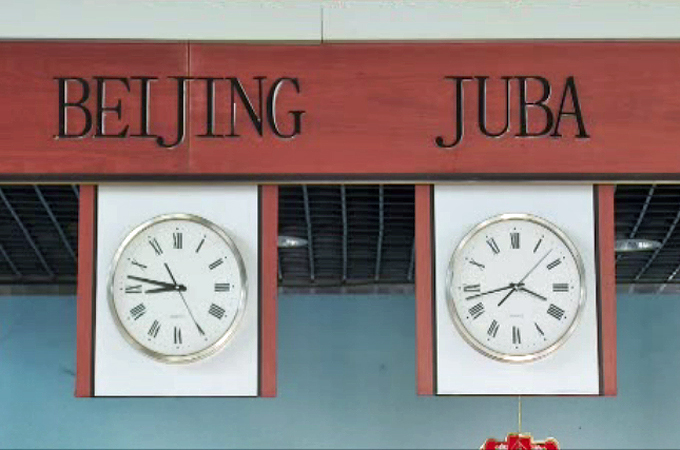

|

| To secure access to south Sudan’s resources, China has started building closer ties with Juba |

To counter this and to secure access to the south’s resources after secession, China has started to build closer ties with the south.

Beijing, to the chagrin of the West, has supported the right of African nations to run their domestic affairs without outside interference, which partly explains the booming trade between the continent and the Asian power.

But by communicating with the government of South Sudan while it is not an official sovereign entity, it is partially abandoning its ‘non-interference policy’ and its traditional reluctance to engage with separatist movements – motivated in part by its own experiences in Tibet and Taiwan.

Richard Dowden, the director of the Royal African Society, says this is because the “Chinese priority is oil”.

“They openly opposed the independence option to start with, but then realised that it would happen and now say they are neutral,” Dowden explains.

“They are beginning to realise that a strict ‘non-interference’ policy is political and diplomatic nonsense. The very relationship between China and an African state is a political act that has implications. The relationship creates a political dynamic that implies support for the ruling group.

“The Chinese are beginning to realise that since so much of African politics is driven by groups or individuals below the official state level they will have to understand and engage with these dynamics. That means meeting leaders of the opposition, negotiating with local chiefs and kings in areas where the Chinese operate even though they have no status at official national level.”

A Chinese consulate was established in Juba, the southern capital, in September 2008. In November 2010, it was upgraded to ambassadorial level, and Li Zhiguo, China’s former envoy to Bahrain, was appointed consul general in Juba.

In October 2010, a delegation of Chinese government leaders visited Juba, where they met with the secretariat of the south’s ruling Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM). Salva Kiir, the leader of the SPLM, and other southern Sudanese government ministers, have also visited Beijing and multiple projects have progressed in the region.

Chasing Chinese investment

Ian Taylor, a professor of international relations at the University of St. Andrews’ School of International relations and author of China’s New Role in Africa, says: “China has implemented various projects in the south and plans more, like building universities, hospitals … and water projects.”

After years of neglect, the underdeveloped south is in desperate need of investment and, according to He Wenping, the director of the African Studies section at the Institute of West Asian & African Studies (IWAAS) at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, understands that “oil cooperation between the north and south is the key for their future development”.

“China’s involvement in the field, including post-referendum economic construction in many other fields, is also important,” He added.

But many southerners have complained about the refineries that have been built on their land and the resulting environmental problems, like water contamination and sprawling lakes of toxic waste, and say that they have seen little of the wealth generated by oil production.

The Chinese are allegedly involved in negotiations over a new 1,400km pipeline, which would link South Sudan to the Kenyan port of Lamu, where it also intends to develop infrastructure. Once completed, the pipeline could serve as an alternative route for the land-locked south.

This development would see about 80 per cent of oil revenue shift from Khartoum to Juba. And despite the assurances of Liu Guijin, China’s special envoy to Darfur, that “China wishes to cooperate with the north and the south,” some suspect that Chinese investments will shift along with the revenue.

But while Beijing’s approach towards Juba is pragmatic, with securing the oil flow the central goal, China has invested an estimated $15bn in the north and is likely to want to maintain its relationship with Khartoum.

Furthermore, Khartoum has proved itself to be a reliable trade partner and ally, while a new government in the south will be an unknown figure in China’s calculations.

So, while CNPC is setting up a branch in Juba, the company remains headquartered in Khartoum.

“It [the secession of the south] wouldn’t have [a] big influence on the current China-Sudan relations,” He says. “While maintaining the traditional good relations with the north, China will also establish good relations with the south.”

From bilateral to trilateral

|

| The Chinese-built Merowe Dam provides Sudan with a stable power grid and revenues from energy sales [EPA] |

But with both the north and south rearming, Beijing is keen to ensure that the referendum does not result in renewed instability, which could threaten its multi-billion dollar investments and potentially impact its growing interests in neighbouring countries like Ethiopia, Chad and Libya.

“Beijing is a supremely pragmatic actor. It is in China’s best interests that the vote goes smoothly and the probable secession by South Sudan is permitted to go ahead peacefully,” Taylor says.

China has sent a delegation to the south to observe the referendum and a foreign ministry spokesman has stressed Beijing’s hopes that the vote will be held in a “fair, free, transparent and peaceful atmosphere and that all parties involved should be committed to peace and stability”.

In turn, the government of South Sudan has assured China that its investments will be protected if the south secedes from the north.

“We have given assurances to the Chinese leadership delegation to protect the Chinese investments in southern Sudan, and are desirous to see more investment in the future,” Pagan Amum, the secretary general of the SPLM, reportedly said.

But despite China’s growing ties with the south and the south’s need for investment, southerners may not have entirely forgotten Beijing’s traditional support for Khartoum. And as US sanctions will only apply to the north should the south secede, the new country could potentially be open to new investors from the West.

Beijing’s efforts to turn its bilateral ties into trilateral relations may just pay off, however, and the repercussions of this could stretch far beyond oil production.

He says China has already played a key role in “consolidating the smooth implementation of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement [the 2005 agreement that brought the civil war to an end and which included the provision of a referendum on independence for the south]”.

Dowden suggests that China could be just as critical to ensuring that peace is maintained after the referendum as, should the south vote to secede, the two sides enter a six-month transition period during which thorny issues such as border demarcation and oil revenue sharing will be negotiated.

“They could be a force for peace if they play their cards right and understand what is going on,” Dowden says. “One of their most important pools of oil lies under the border so they will be desperate to make sure a war does not break out.”