South Sudan braces for trouble

In the religiously mixed border towns residents fear they will be on the frontline of any post-referendum violence.

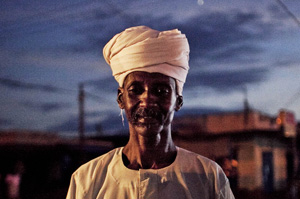

The scene after dark in this lively market in the northernmost tip of southern Sudan is more reminiscent of the Middle East than of East Africa, but both regions are represented here. Northern Sudanese men in jalabiyas and skullcaps smoke shisha alongside lanky, dark-skinned southerners. Ethiopians serve roast chicken in an outdoor restaurant next to a tea shop run by Darfuris.

This unique merger of cultures in the southern town of Renk is symbolic of Sudan’s immense diversity, and the thriving town benefits from its ties to both the north and the south.

On its surface, Renk is reminiscent of the late southern rebel leader John Garang’s vision of a “New Sudan” – a place where the enormous diversity of Africa’s largest country can be of mutual benefit to its peoples instead of a cause for conflict or exploitation.

Since Sudan’s long civil war ended in 2005, the town of Renk has reaped some significant dividends from peace. Twenty-four hour electricity illuminates the town, courtesy of the national grid connection from the north. Cheap goods are available thanks to the paved road running to Khartoum.

Meanwhile in Juba, the southern capital, unreliable “city power” means only expatriates and wealthy Sudanese have consistent electricity due to generators, and products imported from Kenya and Uganda are expensive given the day-long or more journey by road from both countries’ capitals.

Desire for independence

Despite the current economic benefits of north-south relations in Renk, the desire for independence among southerners is strong here. Like many other towns across the south, Renk has been holding pro-separation rallies on the ninth of each month in anticipation of January 9, the date currently set for south Sudan’s independence referendum.

It is believed that southerners will vote overwhelmingly for separation. “I support separation because I want to feel like a human being,” said Siham Abdelatti, 36, a tea seller in Renk’s bustling market.

Abdelatti’s grandparents fled from Darfur more than a century ago to escape slavery and settled north of Renk in a small village near the border.

| IN PICTURES: DRAWING NEW LINES |

|

|

Her father married a southern woman from the Dinka tribe, and she said she is proud of being a “mix of northern and southern Sudan,” although she is careful to stress that she is a southerner who has the right to vote in the upcoming referendum.

Hussein Bashir, a young northern Sudanese man from a town near Khartoum, peddles bananas, apples and grapefruits at his father’s stand in the night market. He says his family moved here in 1997 because they did not have the means to have a similar business in the north.

“We’re comfortable here,” Bashir said, pulling bananas hanging from the top of the stand and putting them in a paper bag for an older southern Sudanese man with skin much darker than his own. “We don’t want to leave because of the referendum but the politics are out of our control.”

Traders from the north have varying degrees of connection to the south – from purely commercial reasons for staying to more permanent links like intermarriage.

Ayuel Yuar, 30, embodies the mixed identity of border communities. He hails from the southern Dinka Abilang tribe but, as a Muslim, serves as a member of Renk’s Islamic Council.

Yuar explained that tensions in Renk are not between Muslims and Christians, but between the competing political agendas of northerners and southerners. “[The northern government] will use religion as a tool of war again because before they were using jihad as a means of fighting the south,” he said. “The southern government will not use religion because it is a secular government. But there will be consequences for Muslims in the south like me. I am afraid,” he added.

‘Pulling at the root’

The majority of Sudan’s known oil reserves lie south of the border, and experts say a substantial proportion of the country’s remaining known reserves are in northern Upper Nile. Some fear that the government in Khartoum will not peacefully relinquish control of them.

The multinational oil consortium Petrodar began pumping oil out of the Melut Basin area south of Renk in mid-2006. At that time, the oil blocks in the area were expected to produce 300,000 barrels-a-day, which were exported through a 865–mile pipeline to Port Sudan on the Red Sea. Petrodar’s production in the area accounted for more than half of Sudan’s total crude output in 2006.

“The north will not just accept and say goodbye to us,” said William Chuol, the police commissioner in Renk. “There will be a pulling at the root.”

Despite their determination to vote for separation and form an independent south, everyday citizens of Renk and local government officials alike are well aware that they live in the zone that would quickly become the frontline if conflict between the northern and southern armies resumes. Military experts say that Renk could be reached by heavy artillery from the northern side of the border.

The southern army’s division headquarters sit on the edge of Renk. The capital of Sudan is roughly 270 miles away, but the northern Sudanese military is massing troops at the current borderline between north and south.

Military observers from the United Nations mission in Sudan have the mandate to monitor the status of forces and the equipment of both the northern and southern Sudanese armies, but the UN does not have the access or ability to regularly patrol on the northern side of the border.

“If the north refuses the outcome of the referendum, then there will be problems,” said Deng Akwei, the Renk county commissioner. “If fighting begins it will be on the border and it will continue from there.”