Is inflation a problem? And if so, who will feel the most pain?

Inflation is in the news because the prices of goods that everyone around the world depends on are going up – like food and fuel. Here’s what you need to know.

As economies recover and big ones continue to benefit from massive injections of government stimulus, a wonky and sometimes scary buzzword has crept back into the conversation: inflation.

Broadly speaking, inflation is when prices rise and the money in your pocket doesn’t stretch as far as it used to. A little bit of inflation is no bad thing. But too much of it can be really, really damaging to economies and livelihoods.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsCommodity prices at eight-year highs, raising inflation concerns

Fed’s Powell ‘honest about the challenge’ amid inflation concerns

US Treasury chief says inflation risk is ‘small’ and ‘manageable’

So is inflation becoming a problem? And if so, who would it hurt the most?

First of all, why is everyone talking about inflation right now?

Inflation is in the news because economies are gearing up again.

As factories and supply chains groan back to life, it’s causing transport bottlenecks, rising shipping costs, and shortages of commodities like copper and oil to produce things.

Another reason inflation is going up is that some governments – notably that of the United States – are spending a lot of money to help their economies recover their pre-pandemic mojo.

So do I have to worry about rising material prices?

You do if factories pass those increased costs on to wholesalers who then pass them on to retailers who then pass them on to you – the consumer – in the form of higher prices.

Are factories passing on higher material costs?

Well, let’s take a look at producer prices, which measure the change in prices that factories charge to wholesalers. In China, producer prices rose 4.4 percent in March on a monthly basis, compared to 1.7 percent in February.

In the US, producer prices rose 1 percent in March over the previous month, which was double the rise seen in February.

Simply put, producer prices are going up.

Is that just a problem in the country where it’s happening?

Not necessarily. China is an exporting powerhouse, so as inflation rises there, it threatens to feed inflation around the world.

What about prices for consumers?

Those are spiking, too. US consumer prices jumped 0.6 percent in March – the biggest monthly jump since August 2012. Nearly half of that rise was due to climbing petrol prices, which rose 9.1 in March from the month before.

In China, consumer prices rose to 0.4 in March.

So will prices continue to climb?

That is a hotly debated question right now among economists and policymakers – especially in the US.

Why?

Because they can’t agree on whether these price surges will prove temporary, or if the US economy is in danger of “overheating”, thanks to the $1.9 trillion in coronavirus relief aid that Congress passed in February. That massive stimulus added significantly more firepower to consumer spending – the engine of the US economy that drives some two-thirds of growth.

What does it mean when an economy ‘overheats’?

When an economy is overheating, demand for goods and services grows so quickly that it outpaces supply, driving up prices. That can incentivise firms to take on debt in order to boost their capacity, in the expectation that the good times will only get better.

That doesn’t sound so bad.

It is, should prices start spiralling viciously upward. Some are worried that if that happens it could prompt the US central bank, the Federal Reserve, to raise interest rates – which cools demand and economic growth.

Then all that spare capacity businesses sunk money into would likely be idled, which means businesses start to lay off workers.

Oh.

Yeah, you get the picture.

So is the Fed going to raise interest rates?

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has repeatedly – and I mean repeatedly – said the Fed will not raise interest rates until the economy has recovered from the ravages of COVID-19. Especially the jobs market, where there’s still a lot of healing to do. Of the 22 million jobs lost to pandemic lockdowns in spring 2020, some 8.4 million have yet to be recovered.

What kind of inflation might I be feeling right now?

If you have a car, you’re likely feeling pain at the pumps.

In the US for example, nearly half of the gain in monthly consumer prices in March was due to rising petrol prices.

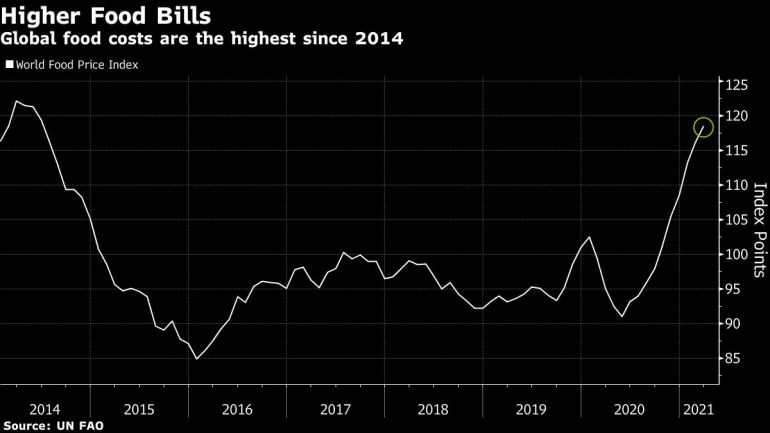

Globally, food prices are also surging. The United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization Food Price Index, which tracks changes in international prices of commonly traded food commodities, rose for the 10th consecutive month in March to its highest level since 2014.

Does everyone feel that pain equally?

No. Rising prices of basic staples are exacerbating inequalities within and between nations. That’s because for low-income households, essentials like food and fuel eat up a larger share of their monthly budgets.

In the US for example, a gallon (3.8 litres) of regular petrol cost an average of $1.92 on April 6, 2020. A year later, it’s up to $2.85, according to the US Energy Information Administration. That 93-cent increase might not seem like much, but it amounts to an extra $11.16 to fill up a small car’s 12-gallon tank.

Who else feels the pain disproportionately?

Inflation also hurts people on fixed incomes – like older folks – because they receive the same benefit each month but due to price increases, they can’t buy as much as they used to with it.

What are the long-term effects of all this?

This disparity has contributed to a K-shaped recovery from the coronavirus recession. The groups that were on top, to begin with – wealthy people, for example, who own houses and stock portfolios and have kept working from home during the pandemic – keep rising, while the bottom – low-wage workers – continue to decline as their purchasing power declines, spurring wider inequality.

Yikes. What about a country where food prices have soared?

People need to eat, and price surges don’t make that any less true.

In Nigeria, inflation hit a four-year peak this February led by a 21.79 percent surge in food prices. The country is already experiencing high rates of unemployment and crime, and experts warn the increase in prices of everyday goods could spark unrest.

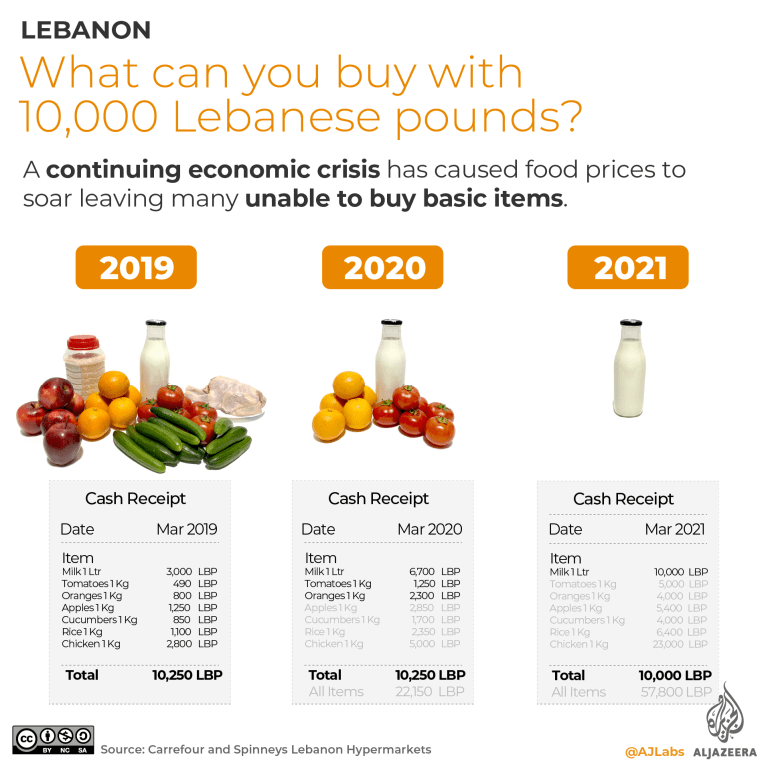

In Lebanon, a country that was already in the throes of its worst economic crisis in decades before COVID-19 struck, the plummeting value of the local currency has decimated purchasing power, causing food prices to soar to five times what they were in 2019.

What about hyperinflation? What is that, exactly?

When prices continue to rise at a rapid pace, an economy can experience hyperinflation, which is generally defined as inflation of 50 percent or more per month.

That makes an economy and a society extremely unstable: the price of goods like bread can literally double in a matter of days, and consumers can need baskets of currency to pay for everyday goods. People don’t know what their money will be worth from one day to the next, which can lead to hoarding and shortages.

That’s horrendous. Is there a country experiencing that right now?

Yes, Venezuela – another economy that was on its knees before COVID-19 struck – is currently experiencing a 2,665 percent annual inflation rate. It takes 400,000 bolivars — the equivalent of 20 US cents — to buy a round-trip transit ticket in the capital of Caracas.

Before hyperinflation hit in 2017, the exchange rate was around 10 Venezuelan bolivars to the US dollar. In August 2018, it jumped to a record 2,45,016 million bolivars to the dollar, and is now about 1,885,284 bolivars to the dollar, according to US Federal Reserve data.

Faced with that plummet in value, the Central Bank of Venezuela recently issued new bills worth more to avoid people having to carry armloads of smaller bills into stores to buy goods. There is now a one-million bolivar bill.

Are there any upsides to inflation?

A little inflation is a good thing because it keeps the economy humming along.

How so?

Because if people think prices will go up slightly, they are less likely to delay purchases. This is why the Fed set its target inflation rate at 2 percent over the longer run. But it has said it is willing to tolerate inflation trending above that target rate for a while as the economy recovers.

Any other benefits to inflation?

If people – or countries for that matter – are deep in debt, inflation can help ease the burden because they are servicing those debts with a currency that is worth less than it was when they borrowed money.