Trade to human rights: Trajectory of Trump’s China policy

Trump doubles down on punishing Beijing economically over Uighurs, while Biden’s China policy remains unclear.

United States economic policy and foreign policy have always been intimately entwined. But what was traditionally a discreet symbiosis cloaked in noble rhetoric of promoting global stability and human rights has been explicitly and unapologetically wedded under President Donald Trump.

Nowhere is that more apparent than in his administration’s myriad confrontations with China.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsTrump v Biden: Who do US consumers think will win in November?

‘War will benefit no one’: Global concern over US-China tensions

Chinese-owned TikTok asks US judge to block Trump’s download ban

Trump has famously labelled COVID-19 the “China virus”, accusing Beijing of covering up the initial outbreak and sowing the seeds of a global pandemic.

Tensions between the world’s two largest economies have steadily escalated since Trump entered the Oval Office promising to get tough on China for what he has described as unfair practices.

It is a promise he has made good on many times over. From slapping tariffs on hundreds of billions of dollars worth of Chinese imports to curbing the global might of Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei, declaring Beijing a currency manipulator, and effectively forcing China’s ByteDance to partner with US companies to keep TikTok US up and running, the Trump administration’s China policy has used economic pain as a cudgel to try and create an edge for the US.

Human rights appeared to only marginally factor into this transactional approach. But in the run-up to the 2020 election, they have increasingly taken centre stage.

Meshing trade with human rights

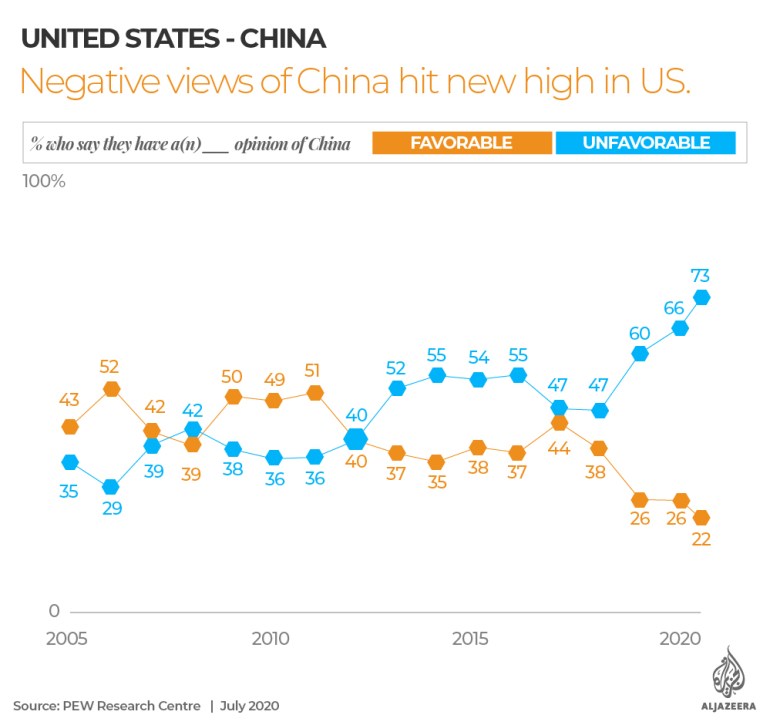

The US public’s view of China has dimmed considerably on Trump’s watch.

A recent survey by the Pew Research Center found 73 percent of US adults view China unfavourably – the most negative view in 15 years and a staggering 26 percentage points higher than 2018.

Since March, when coronavirus lockdowns swept the nation, triggering the sharpest quarterly recession on record, negative views of China spiked 7 percentage points, Pew found.

That same survey showed a majority of Americans – nearly three-quarters – favoured promoting human rights in China over US-economic relations.

That preference was strongest among Democratic and Democratic-leaning voters.

Earlier this month, the US Customs and Border Patrol agency issued orders blocking imports of certain products from the Xinjiang region of China, citing concerns about forced-labour involving Uighur Muslims.

In August, the United Nations said it had received credible reports that more than a million Uighurs have been held by the Chinese government in massive internment camps.

Beijing describes them as “re-education camps” that provide vocational training.

The CBP orders followed on from earlier blacklists of Chinese companies suspected of using forced labour – part of a flurry of activity that has seen human rights move to the forefront of the Trump administration’s confrontations with China this year.

On July 9, the US slapped sanctions on Chen Quanguo, a member of China’s powerful Politburo, and three other senior officials, accusing them of serious human rights abuses against the Uighurs.

Later that month, more officials and the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps or XPCC were blacklisted by the US Treasury for alleged human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

Known as “bingtuan”, the XPCC runs vast agricultural enterprises across Xinjiang, and is described by the US Treasury as a paramilitary organisation that is subordinate to the Chinese Communist Party.

The Trump administration revoked Hong Kong’s preferential economic status this summer and blacklisted officials from Hong Kong and the mainland in response to a sweeping national security law that threatens to chill liberties in the semi-autonomous territory.

The US also ordered the Chinese consulate in Houston to close. Beijing retaliated by ordering the US to shut its consulate in the southwestern city of Chengdu.

Together, these actions have kept the spotlight on Trump’s increasingly hostile approach to China in the run-up to the November 3 election, as he seeks to depict his opponent, Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden as weak on foreign policy, generally, and China, in particular.

“China will own the United States” if Biden wins, Trump has said.

But according to former US National Security Adviser John Bolton, Trump’s focus on promoting human rights through economic penalties represents a U-turn.

Bolton wrote in his recently published memoir the president had been uninterested in the plight of China’s Uighurs, preferring to take a soft line as he tried to broker a resolution to the trade war with Chinese President Xi Jinping and boost Chinese imports of US goods to curry favour with US voters.

In The Room Where It Happened, Bolton wrote of a meeting between Trump and Xi in Japan last June, during which Trump “stressed the importance of farmers and increased Chinese purchases of soybeans and wheat in the electoral outcome”.

Bolton wrote that during the same meeting, Trump told Xi building the camps for Uighurs “was exactly the right thing to do” and urged Xi to go ahead.

Trump now appears to have meshed his approach to trade with human rights, pre-empting Biden, who has significantly hardened his rhetoric against Beijing, even referring to President Xi as a “thug”.

2020 double-down

Trump’s belligerence towards China resonated with voters on the campaign trail in 2016. Before he even took office, he telegraphed his intention to shake things up dramatically, when he broke with nearly 40 years of US foreign policy by becoming the first US president-elect to accept a congratulatory phone call from the president of Taiwan.

Under the “one China” policy, which the US has acknowledged since 1979, Beijing views Taiwan as part of China.

Once in office, Trump declared trade wars to be “good” and launched his with China, levying tariffs on Chinese goods that prompted Beijing to slap retaliatory sanctions on US goods – actions that have damaged both economies.

As the US elections have drawn near, Trump has been doubling down on his tough stance on China.

In August, the US approved the sale of F-16 fighter jets to Taiwan. Beijing was incensed.

Trump also signed an executive order banning any transactions with the Chinese owners of the immensely popular apps TikTok and WeChat.

Meanwhile, Biden has yet to set out policies specific to China, but some analysts say he would be expected to hold Beijing to account on human rights abuses, intellectual property violations, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the unresolved trade dispute.

Biden had long pursued the line that the US did not regard China as a competitor, though analysts say the pandemic has changed his approach.

Many foreign policy wonks believe a Biden administration would likely reset and reprioritise US relationships with allies and international organisations such as NATO; check China’s growing influence within the UN agencies; and reassert leadership on matters of global importance, which has been glaringly absent throughout the COVID-19 crisis.

Where Beijing stands in terms of presidential preference is open to debate.

China, along with Russia and Iran, has been suspected of working to undermine the US election, according to William Evanina, director of the National Counterintelligence and Security Center. He said last week China views Trump as “unpredictable” and does not want to see him re-elected.

Yu Jie, an analyst at London’s Royal Institute of International Affairs, however, said Beijing has yet to decide on a more favoured candidate, but would likely prefer the more predictable approach of a Biden White House.

It is not a choice between a good or bad relationship, she told Al Jazeera, but what sort of a bad relationship does Beijing want with Washington.

“I don’t think China has made up its mind yet [which candidate it prefers] because there is a realisation that, irrespective of who occupies the White House for the next four years, the relationship with the United States is going to be a troubled one,” she said.