From trade to TikTok: How US-China decoupling affects everyone

Four decades of policies that encouraged China to become more economically integrated with the world are unravelling.

Before he died in 1994, former United States President Richard Nixon had an “uh-oh” moment of historic proportions, at least according to his speechwriter William Safire – a moment of doubt that is reverberating to this day.

“I asked him – on the record – if perhaps we had gone a bit overboard on selling the American public on the political benefits of increased trade [with China],” Safire wrote in an opinion piece for The New York Times in 2000.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsPolitics and convenience drive Mexico to be US’s top trading partner

Will Xi and Biden mend US-China relations at the APEC summit?

UK warns of Russia laying ‘sea mines’ to deter Black Sea cargo ships

“That old realist, who had played the China card to exploit the split in the Communist world, replied with some sadness that he was not as hopeful as he had once been: ‘We may have created a Frankenstein’,” Safire quoted Nixon as saying.

Last month, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo invoked that apocryphal mea culpa in a speech at California’s Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, as he and his boss, President Donald Trump, attempt to put China back into a Cold War-like deep freeze.

Pompeo said Washington and its allies must use “more creative and assertive ways” to press the Chinese Communist Party to change its ways on unfair trade practices, human rights abuses and efforts to infiltrate US society, calling it the “mission of our time”.

The irony, of course, is that their late Republican hero had made thawing out China’s relationship with the West the centrepiece of his presidency – while he was not battling political scandals, that is.

“There is no place on this small planet for a billion of its potentially most able people to live in angry isolation,” Nixon famously wrote in October 1967, setting the tone for his policy of detente towards China once he entered the White House in 1969.

The decades that followed have seen China rise from the ashes of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution to become the world’s second-largest economy. Today, it is anything but isolated, even if not everyone is its friend. Few, if any, countries can say they are not affected by China, either politically, economically or both.

But as the economic war between the US and China morphs into a rapidly escalating political dispute, threatening their phase-one trade deal reached in January, the close ties the two countries have built up since the 1970s are unravelling. This is creating opportunities for some commercial interests on both sides, but also risks for others.

And while the two giants slug it out, many smaller economies are being forced to take sides. The collateral damage of the great US-China decoupling is spreading.

Front lines

Some aspects of the decoupling of the world’s top two economies had begun even before Trump took office in 2017. Rising costs in China, increased automation – and growing anger at Beijing’s appropriation of intellectual property in exchange for access to its markets – had already been pushing some Western companies to start looking at alternatives to China.

But the US-China trade war forced many firms to move quickly.

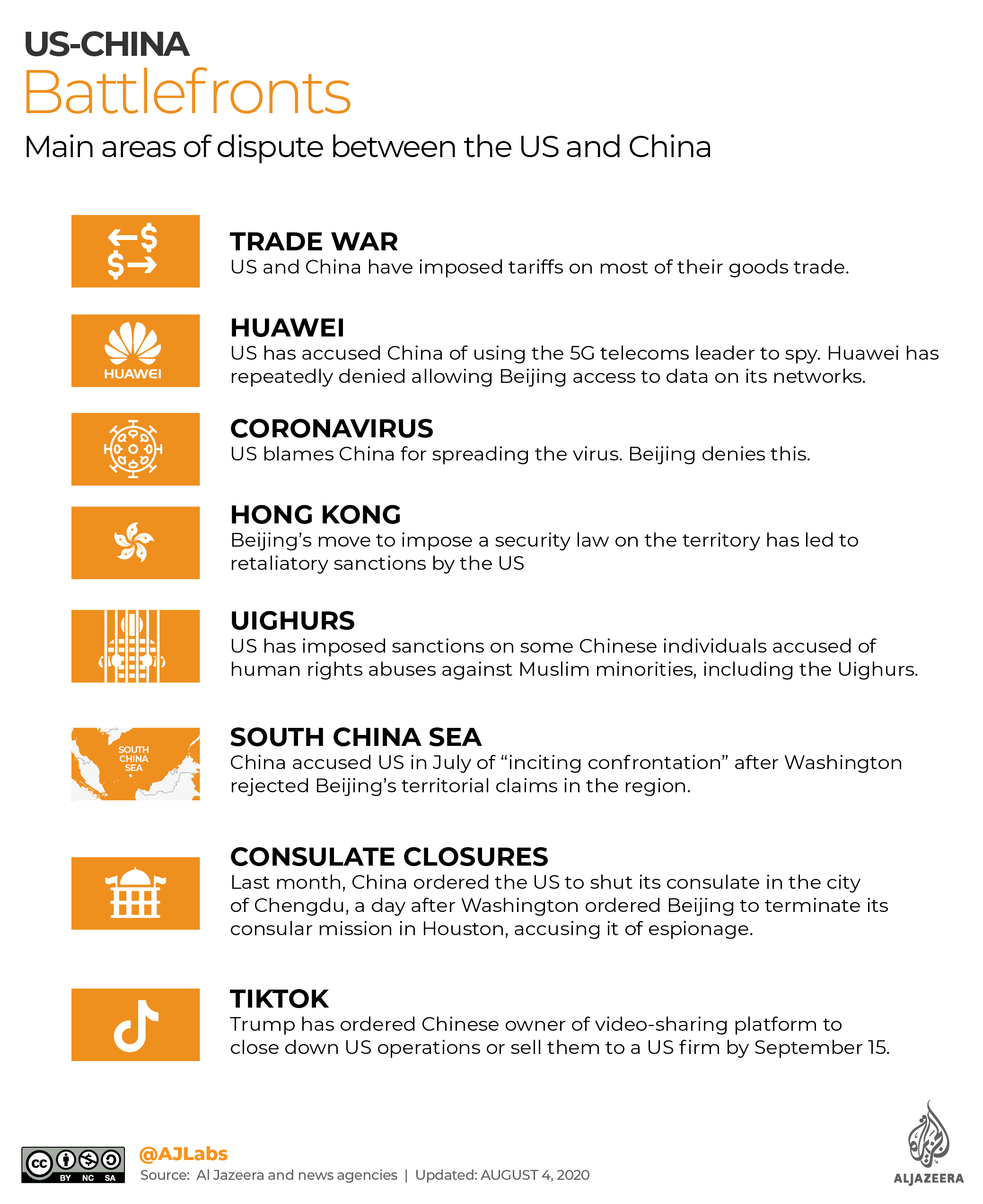

There are now a number of fronts along which the two countries are engaged in direct economic or political conflict.

These include punitive tariffs placed by the US on about $370bn worth of Chinese imported goods, and retaliatory levies by China; the US’s accusations that Chinese telecommunications equipment maker Huawei Technologies helps Beijing snoop on its enemies; the coronavirus; a row over Beijing’s move to impose a security law on Hong Kong; US sanctions on some Chinese individuals linked to alleged human rights abuses against Uighurs and other minority Muslim groups; territorial disputes in the South China Sea; and most recently, the tit-for-tat closures of each other’s consulates in Houston and Chengdu.

All these developments have pulled the two superpowers further apart. The tariff war in particular has made a sizeable dent in both economies.

The US Federal Reserve estimates the conflict (PDF) has resulted in a net loss of employment among US manufacturers in the first half of 2019, while the Federal Reserve Bank of New York says the trade war wiped $1.7 trillion off the value of US-listed firms over the two years since it began.

Meanwhile, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development says higher US tariffs on Chinese goods resulted in a 25 percent dropin Chinese exports to the US, and tens of billions of dollars of losses for Chinese firms.

One direct consequence of the trade war has been to force some US companies that had over several decades outsourced manufacturing to low-cost centres – including China until recently – to accelerate plans to move some of those activities back home, a process known as “reshoring”.

Research firm Enodo Economics says the sectors most likely to do this are makers of cars and electrical machinery, wood processors, chemical firms and companies involved in railways, shipping, aircraft and pharmaceuticals.

But reshoring might be easier said than done.

Modern manufacturers farm out the production of components to other companies, which might in turn hire others to make the bits that go into those parts, and so on down the value chain. Thus, moving one part of such a supply chain somewhere else would require a complex – and costly – rearrangement of capital and labour, affecting countless numbers of people, many in economically disadvantaged countries.

And the difficulty of moving highly interdependent production lines appears to be playing into China’s hands.

“Trade tensions between mainland China and the US appear to have raised, not lowered, the reliance of third markets on inputs from mainland China,” according to research by global banking giant HSBC.

“Mainland China continues to raise its global market share as a component supplier in electronics, pharmaceuticals, and autos,” HSBC said in a July research note sent to Al Jazeera.

Winners and losers

But more broadly, the economic realignment of the US-China axis is forcing almost every country that deals with them to rethink what they do.

Several Asian countries could become beneficiaries of the great decoupling. And the US’s disengagement from multilateral trade agreements appears to be pushing those countries towards China’s sphere of influence.

“For most economies in Asia, China has already eclipsed the US not just as a trading partner, but as a source of final demand,” wrote Frederic Neumann, HSBC’s co-head of Asian economics research, in a note to clients.

For instance, HSBC says, Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea could see significant gains in income by 2030 from their membership of two major regional free trade agreements. China is a big player in one of them, while the US is not a part of either.

But for some companies, the US-China divorce is proving to be particularly awkward.

After Beijing enacted its Hong Kong security law, London-based banks HSBC and Standard Chartered publicly supported the move, breaking their silence on political matters despite intense opposition to the legislation by many in the territory. Both lenders count Hong Kong as their biggest market. Even before the security law controversy, pro-democracy protesters had attacked HSBC’s iconic bronze lions – named Stephen and Stitt – outside its Hong Kong office in January over its perceived ties to Beijing.

TikTok, the Chinese-owned video-sharing app that has become wildly popular with teens the world over, has found itself in Trump’s crosshairs. Trump accuses its owner, ByteDance, of allowing the Chinese government to gather the data of TikTok’s users, something TikTok has denied.

That controversy has drawn in US tech giant Microsoft, which is now trying to buy TikTok and sever all the social media platform’s links with Beijing.

If the deal succeeds, it would be a prime example of how a successful US-Chinese commercial relationship – most of the funds that ByteDance raised came from the US – has unravelled. An editorial in the Beijing-backed China Daily newspaper on Tuesday complained that the US is “bullying” Chinese tech firms.

Meanwhile, India has its own issues with China over data security. After the two engaged in a deadly border skirmish in June, India banned nearly 59 Chinese mobile apps, including TikTok.

The battle of Huawei

But it is Huawei that provides arguably the best example of just how far the fissures from the US-China split have reached.

The Chinese firm reportedly owns the highest number of patents relating to equipment running the newest-generation 5G mobile phone networks.

The stakes for 5G are huge. Research firm IHS Markit estimates that by 2035, 5G technology will help to create more than 22 million jobs worldwide and generate $13.2 trillion worth of economic output annually. That is roughly the amount that US consumers spent last year, or the combined consumer spending of China, Japan, Germany, the United Kingdom and France in 2018.

The US claims Beijing can use Huawei’s equipment to gain access to confidential data, something Huawei has long denied. The Trump administration has banned American telecommunications firms from doing business with Huawei.

But the US is also pressuring its allies to ditch Huawei, leaving many countries that rely on the firm’s equipment to build affordable 5G networks in a quandary.

For instance, after initially allowing Huawei in January to build parts of the UK’s so-called non-core 5G network, with some security restrictions, the European Commission gave a similar green light to its member countries to do the same.

The US turned up the pressure on the UK to reverse its decision, and in May, London said it would review it. Last month, the UK also banned Huawei from its 5G roll-out.

And following that decision, the European Commission said member countries must take urgent action to diversify their 5G suppliers, without mentioning Huawei by name.

The winners of such a diversification could be Finland’s Nokia and Sweden’s Ericsson, direct competitors to Huawei. They scored one such victory last month, when Singapore – a small trade-dependent Asian nation with deep economic, political and cultural ties to China – announced that it would choose the two European firms for its 5G network over Huawei.

But Nokia and Ericsson are themselves reliant on China for many of the components that go into their network equipment. They operate factories employing thousands of people in the country.

The Wall Street Journal reported last month that Beijing is considering retaliatory measures against the two firms if the EU follows the US and UK in banning Huawei, citing people familiar with the matter.

Nokia and Ericsson could relocate their Chinese manufacturing plants, perhaps to another part of Asia, but at a significant cost. And for countries forced to use competing firms, the costs of building 5G networks without Huawei could be much higher.

The result could be delayed roll-outs of 5G, or worse still, systems in one country that are incompatible with those in another, reducing the smooth flow of information and knowledge across borders, reinforcing and accelerating the breakdown of global commerce and progress.

But as high as the stakes are with 5G and other disputes, right now, nothing could be more important than how the deteriorating US-China relationship is affecting the global fight against the coronavirus.

A coordinated response to the pandemic in its early stages might have saved countless thousands of lives. Instead, the mutual suspicion and outright hostility between the two nations has resulted in missed opportunities to fight the virus and protect the global economy.

Trump pulled the US out of the World Health Organization in May, blaming it for helping China cover up the pandemic early on.

Thomas J Christensen, a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a former US deputy assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs, wrote in May: “The finger pointing and politically driven accusations between the worlds’ two leading powers … might have catastrophic results, particularly when the virus spreads to the world’s most impoverished nations.

“China and the United States should be behaving like confident great powers, not like insecure and tragically flawed players in an ancient Greek drama.”