Ecuador unrest: What led to the mass protests?

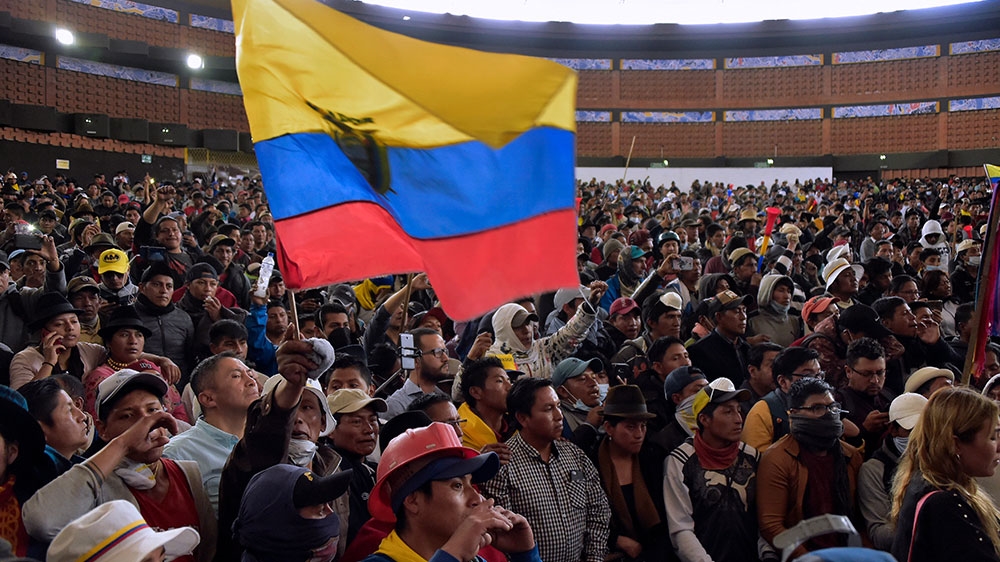

For more than a week, mass anti-government demonstrations over fuel subsidy cuts have paralysed parts of the country.

Quito, Ecuador – Mass anti-government protests have paralysed Ecuadoran transportation and other services for more than a week.

Protesters are angry over President Lenin Moreno’s decision to cut decades-old fuel subsidies and implement tax and labour reforms.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWhy are nations racing to buy weapons?

Parallel economy: How Russia is defying the West’s boycott

US House approves aid package worth billions for Ukraine, Israel

“The people, united, will never be defeated,” demonstrators chanted as they briefly breached a security line and entered the National Assembly on Tuesday.

The protests have at times turned violent with police using tear gas, pepper spray and sound bombs on demonstrators, some of whom have responded by throwing rocks and Molotov bombs. At least five people have been killed and hundreds wounded. More than 700 people have also been arrested.

It is the worst unrest the country has seen in more than a decade.

As things continue to escalate in Ecuador, Al Jazeera takes a look at what prompted the protests and where they may be headed.

1. What prompted the protests, and when did they start?

Protests began on October 3 when President Lenin Moreno cut petrol subsidies that had been in place in the country for 40 years. The cuts saw the price of diesel more than double and petrol increase by 30 percent, overnight.

The government also released a series of labour and tax reforms as part of its belt-tightening measures it was forced to undertake when it agreed to a $4.2bn loan with the IMF.

Some of the more controversial reforms include a 20 percent cut in wages for new contracts in public sector jobs, a requirement that public sector workers donate one day’s worth of wages to the government each month, and a decrease in vacation days from 30 to 15 days a year.

2. Who is protesting and why?

Transportation unions (taxis, trucks and buses) were the first to organise a national strike, blocking roads and highways and bringing the country to a stand-still Thursday and Friday of last week. After talks with the government, national transportation union leaders called off the strike last Friday.

But mass protests continued, with thousands from the indigenous movement, student groups, human rights organisations, labour unions, and local transportation unions taking to the streets throughout the country.

They have pledged to stay in the streets until the government reverses the reforms and cuts. They argue they are bearing the brunt of the measures, which is untenable for many in a country where the minimum wage is just $394 a month.

“The proposed reforms mean eliminating labour rights that workers have long fought to achieve,” Maria Voada, 56, told Al Jazeera in a violent protest Monday. These reforms, “affect the people, the popular lower classes”.

3. What does Moreno and his government say?

President Moreno called a national state of emergency last Thursday only four hours after the first protests began, which put more riot police and army officials on the streets across the country.

He has remained firm that he will not repeal the reforms or reinstate petrol subsidies, which he claimed distorted the economy and cost the country $60bn.

Over the past week, Moreno has moved the government out of the capital Quito, denounced the violence, and accused protesters of being part of a larger plan to destabilise the government, orchestrated by former President Rafael Correa, who lives in Europe. Moreno served as vice president under Correa, and was elected in 2017 based on continuing his left-wing platform. But weeks after the election, he broke with most of Correa’s policies.

Correa has denied any involvement with organising protests, but has been encouraging new elections.

4. Is there a chance at dialogue or the protests ending soon?

It is hard to see an end in sight, as protesters are demanding the government call off the state of emergency, reinstate petrol subsidies, and repeal the labour and tax reforms – calls Moreno has already refused.

The president has called for a dialogue with the indigenous movement, which is the most organised and numerous of the groups involved in the protests.

But Jaime Vargas, leader of the national indigenous movement CONAIE, told Al Jazeera he will not speak to the government until it agrees to repeal the reforms. The indigenous movement also has their own grievance. They are also protesting against extraction activities in their territory, a fight that has been ongoing with the state for over 12 years, Vargas said.

5. What is Ecuador’s history with political instability?

Ecuador has an extended history with political unrest and instability

Since 1997, the Ecuadorians, largely led by the organised indigenous movement, have forced three presidents out of office.

The last overthrow was the right-wing government of Lucio Gutierrez in 2005. Gutierrez tried to implement a series of harsh austerity measures after agreeing to a stand by an arrangement with the IMF in 2003.

Vargas said it is not the intention of the indigenous movement to remove the current government.