Villager number nine

For some Kashmiris, the conflict means being reduced to a number in an Indian army register.

|

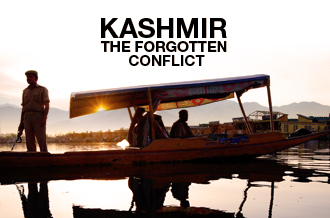

| Military checkpoints dot the Kashmiri landscape [Credit: Showkat Shafi] |

In one of the remotest villages in Bandipora, about 72kms from Srinagar, the capital of Indian-administered Kashmir, an old two-storey wooden house sits on a picturesque hilltop. It is surrounded by coils of barbed wire interspersed with empty alcohol bottles. It is no longer a home; the Indian military have turned it into a military camp. But before the military paint, troops and barbed wire arrived, it was the most beautiful house in the village. Not anymore.

Now an Indian soldier sits in the garden, close to the road and beside a neglected flower bed. On the table next to him is a worn-out register where he notes the number of every vehicle entering the village. Any person going into or leaving the village must register at the camp. Vehicles are checked, the purpose of the visit enquired and multiple entries made in the soldier’s book.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsChina’s economy beats expectations, growing 5.3 percent in first quarter

Inside the pressures facing Quebec’s billion-dollar maple syrup industry

Manipur’s BJP CM inflamed conflict: Assam Rifles report on India violence

The military camp is the gateway into and out of the village. At any point in the day, the soldiers know exactly who is at home and who is away. Just as it has been for decades.

To reach the village you must navigate a difficult mountainous track. The road is in bad shape and remains cut off from the rest of the valley as a result of heavy snowfall during winter. It is a journey that would take hours on foot.

On the road we encounter an old man carrying a hen he purchased in a nearby town. He has already walked for hours and still faces an arduous climb to reach his home. We stop to give him a lift and the old man, who says he knows everybody in his village, including the soldiers, offers us any help we may need while there in return.

Stammering as he talks, he explains that there is a boed-doh (holy day) coming up at one of the shrines in Bandipora. The hen, he says, is to be fed well until the boed-doh when she will be sacrificed. He caresses her from time to time to keep her calm.

Suspicion

As we approach the military camp, the soldier rises from his chair – clearly surprised to see an unknown car.

The old man climbs out first. Turning to the soldier, he raises his hands, expecting to be recognised. But the soldier is more interested in the unfamiliar faces inside the car. Suspicious looks are exchanged. The soldier enquires about the purpose of our visit, checks our vehicle, our identity cards, quizzes the driver and then goes on to make multiple entries in his register.

But the old man is uneasy. The soldier has not recognised him and this worries him. Hen still in hand he approaches the soldier again, repeatedly saying: “Number nine, number nine ….”

|

He stresses the ‘nine’ because that is what the old man is to the soldier – ‘number nine’. That is how he has known him over the years – reduced to a lifeless number entered into a register.

“Number nine?” the soldier asks, looking up from his register.

“Han, jinaab (Yes, sir),” the old man quickly replies in Urdu, without stammering.

“Kahan gaya tha (Where had you been)?” the soldier asks.

“Koeker lanay jinaab (To buy the hen, sir),” the old man says in the best combination of Urdu and Kashmiri words he can muster.

Then, much to the discomfort of the hen, the old man raises her as evidence for the soldier who smiles at the gesture. The hen flaps her wings in a futile effort to break free but her legs are tightly tied together.

The soldier recognises the old man’s number from the register and crosses out the entry he had made earlier in the day when ‘number nine’ left the village. The old man smiles with relief. His number has been identified. He has been recognised.

Once back in the car, the old man explains how that exercise is repeated every time somebody enters or leaves the village. The soldiers have assigned numbers to the villagers. If their number is on the register of the military camp, the villager exists. Numbers matter to the soldiers, names do not. The register is heavy with page upon page of numbers.

Sometimes, the old man says, the soldiers confiscate the villagers’ identity cards. They are returned only when the villager returns to the village. And sometimes they are not returned at all. The villagers cannot ask for them to be returned because they are only supposed to address the soldiers when answering their questions.

Some hours later when leaving the village, the same soldier stops us, checks the vehicle and makes another entry in his register. We are leaving behind the people of this beautiful village; people who have been reduced to numbers.

As we drive along a road in Bandipora, we notice another army checkpoint with a by now familiar message for the people of Kashmir: ‘Prove your identity.’ And on the door of yet another checkpoint, the words: ‘All suspect. All respect.’