A Japanese imperial soldier’s crusade against war

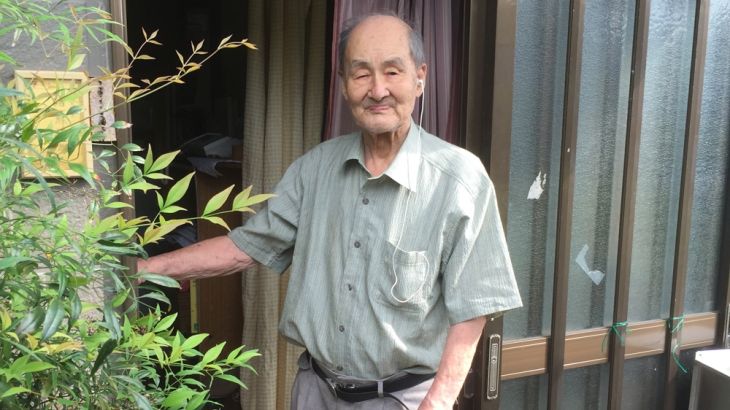

Tokurou Inokuma, 86, says his experience during World War II forged his principle against armed conflict.

Tokurou Inokuma retains much of the self-reliance and self-discipline drilled into him as a young imperial soldier. But he disavows almost everything else he was taught.

The military I joined invaded other countries, abused and humiliated their people, and I was one of its member, and that is an inescapable truth.

Dealing with the loss of his wife, and the effects of a stroke, he lives by himself in a tiny half-bungalow in Yokosuka, south of Tokyo.

Everyday provisions are stacked on the kitchen floor; laundered clothes hang neatly from a rail; his curtained-off bedroom-cum-office is packed with files and photographs.

At 86, Inokuma is the youngest surviving former member of Japan’s Imperial Army.

He signed up at the age of just 15, despite his father’s objections. It was 1943, and Japan had decided to recruit teenage “special military cadets” to swell the ranks of its army.

He was full of the patriotic fervour and racial superiority he’d been taught. His first experience of battle, a US air-raid on his mainland military base, came as a harsh first lesson in the reality of war.

“We were raided by carrier-based aircraft for two days in February 1945,” he recalled.

“This was when I lost 20 comrades. I managed to evade the machine-gun fire, but for the first time I realised that war was not something simple or easy. The fight was a matter of either killing or being killed, and I felt it down to my bones.”

‘Attack number one’

But it was when he was assigned to join the Japanese forces in Manchuria, in China, that his faith in the rightness of the cause started to fray.

“The idea was to build an ideal, prosperous nation of five ethnic groups. Not by the force used by the West, but by the rule of Eastern virtue.

“What was it really like? As a child soldier, I wanted to see it for myself. My very first shock, that made me think, ‘What is going on?’, was when I was going out into town for the first time.

“There was a uniform inspection, and we were told we could not leave without totsugeki-ichiban.”

Related: Is Japan’s grief over WWII aggression profound enough?

Totsugeki-ichiban was the slang for a condom. Perhaps tellingly, for an army accused of systematic abuse of Asian women, it translates as “attack number one” or “attack champion”. Inokuma protested.

“I was a child soldier, so I wouldn’t need such things. I said, ‘Why should I carry it? Is this what a proud Imperial soldier would do? Go to comfort stations, brothels?’

“When I said that, the superior officer said, ‘Are you insulting me?’. He pummelled me, kicked me, stomped on me and I was covered in blood. My first outing in China was banned. I cannot forget this.”

Even after Japan’s surrender on August 15, 1945, Inokuma’s war went on. The Soviet army attacked, leaving Japanese forces unsure whether to fight, commit mutiny, or run for their lives.

Inokuma was caught, and spent two years in a Siberian labour camp, watching fellow soldiers starve to death.

‘War is killing’

Now, he and a dwindling group of like-minded former soldiers campaign to ensure no other young Japanese men and women find themselves fighting on foreign soil.

|

|

Inokuma is a vehement opponent of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s policy of loosening the constitutional restrictions on the military, allowing troops to fight overseas in defence of an ally. It’s a policy the government calls a “normalisation” of Japan’s status, as the surrounding security environment changes.

For Inokuma, it’s a betrayal of the pacifist post-war constitution.

“Without knowing war, and giving it excuses like protecting the nation and remilitarising. It is abominable, an absolute nonsense.”

As an aeronautical communications officer he never, had to kill, he said. But he still feels a collective guilt.

“The military I joined invaded other countries, abused and humiliated their people, and I was one of its member, and that is an inescapable truth.”

So what would he say to that 15-year-old boy, now?

“Don’t do such a stupid thing as to become a soldier! That is what I would say. I am the living evidence. War is killing. It is nothing other than killing.”