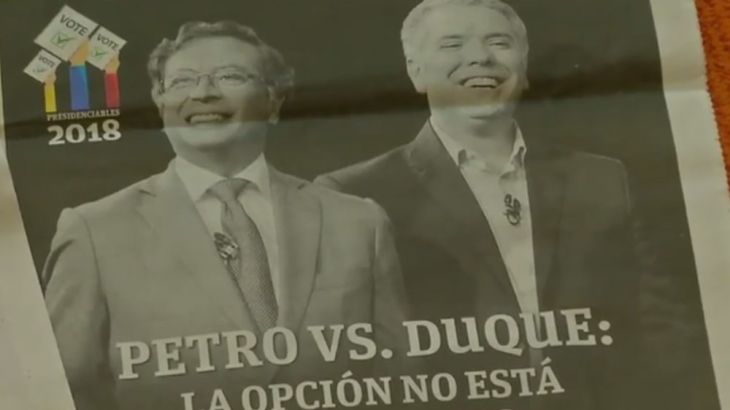

Colombia’s presidential runoff: What to expect

Second-round showdown between Ivan Duque and Gustavo Petro will likely impact a still fragile peace agreement with the FARC.

If you were once an M-19 Marxist rebel and a fan of Venezuela’s deceased populist leader Hugo Chavez, it would be difficult as an elected president to convince moderate Colombians that you would not be a threat to Colombia‘s political and economic stability.

It is precisely that fear factor, aggressively promoted by right-wing opponents, that left-wing presidential candidate Gustavo Petro must overcome before runoff elections on June 17.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsFull jury panel seated on third day of Trump’s New York hush-money trial

Jacob Zuma’s nine lives: How South Africa’s ex-president keeps coming back

A flash flood and a quiet sale highlight India’s Sikkim’s hydro problems

And he is wasting no time.

Speaking before a large crowd of supporters on Sunday, he said he had no intention of taking from the rich to give to the poor.

“No, I want to make the poor rich, to allow them to become part of the middle class that should be the majority, not the minority,” Petro declared.

Petro will have an uphill battle in trying to win over votes that went to the political centre, especially to Sergio Fajardo, the centre-left Progressive Party candidate and former governor of Antioquia State, who narrowly came in second place to Petro.

“I think that Petro’s programme is not a left-wing programme,” Liberal Party politician Jaime Castro said.

“It is fundamentally a populist one,” he added.

“Some consider him a left-wing politician, because he was an urban guerrilla, and because for a while he was a member of the left-wing party, Democratic Pole. But today the essence of his campaign is imminently populist.”

Can Ivan Duque win?

Conservative candidate Ivan Duque, who won 39 percent of the votes against Petro’s 25 percent, still has to fight to make it past the finish line first in the runoff.

He has little political experience and is widely seen as the stand-in for Colombia’s still popular, but controversial former right-wing President Alvaro Uribe.

He favours forcibly eradicating coca crops and opposes abortion and same-sex marriage. But most of all, he wants to alter the landmark peace agreement signed between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) rebels in 2016, that put an end to half a century of civil conflict.

“It’s not true that I want to destroy the agreement. But we can’t let the rebel kingpins make a laughing stock of our democracy and our laws. They must be held accountable for crimes against humanity and serve prison terms. Otherwise, there will never be peace in Colombia,” Duque told me.

Weakness of traditional political parties

The first round of Colombia’s elections underscored the weakness of Colombia’s traditional political parties.

Their candidates scored very poorly, defying the old maxim that their “political machinery” could always be counted on to get out the vote.

Still, Duque represents a regression to the staunchly anti-labour, anti-left wing and pro-big business policies of Alvaro Uribe, despite all of his efforts to paint himself as his own man.

His second round campaign is focusing on his vow to be “the president who will unite all Colombians and end class warfare”.

What is clear is that Colombians have narrowed down the choices for president to two candidates who represent radically different options for the country’s future.

However, many people who voted for neither one do have a third choice.

“I don’t want either of these two extremists to be my president, so in the runoff, I will cast a blank ballot,” Juan Carlos Ramirez told me.