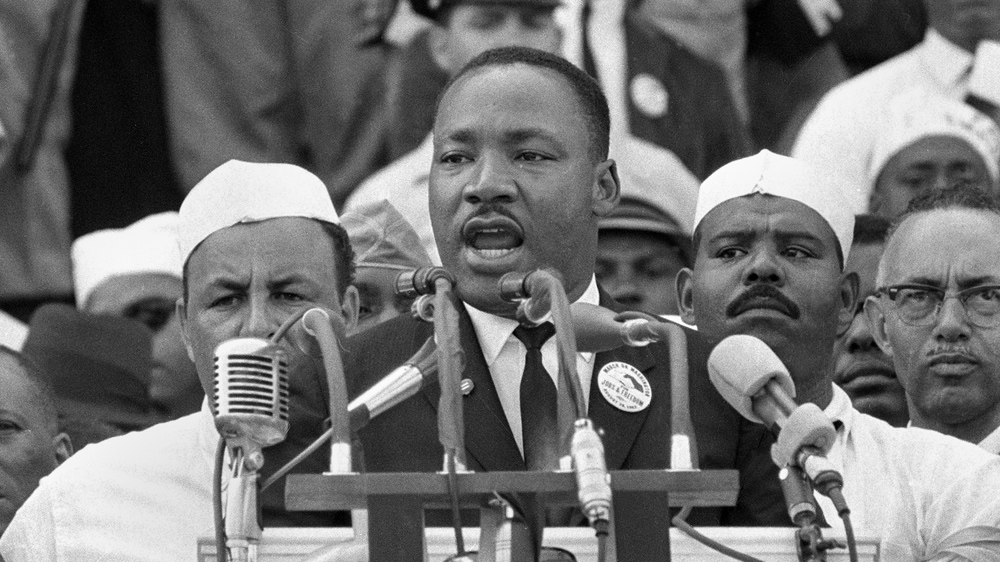

Memphis, 50 years after Martin Luther King Jr’s assassination

Decades after King’s assassination, the southern US city still faces the racial problems the late civil rights leader fought against.

Martin Luther King Jr travelled three times to Memphis, Tennessee in 1968.

The first time, he spoke in support of black sanitation workers who were striking.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsFears of discrimination in Thailand despite looming same sex marriage bill

Hong Kong legislature passes tough new national security law

Why is India’s Citizenship Amendment Act so controversial?

The second time, he watched a march disintegrate into a riot and his reputation as a non-violent activist shatter.

The final time, King left Memphis in a coffin, the victim of an assassin’s bullet.

The sanitation workers had been on strike since February. They wanted more money, better working conditions and respect.

Henry Loeb, the mayor, was refusing to recognise the workers’ union and demands – even after two workers had been crushed to death by accident while sitting inside a rubbish truck.

Race was at the heart of the tension between the workers and the city, but the impact was economic.

Black people earned far less than white people, and their living conditions proved it.

King wanted to highlight that. His long-term goal, according to his biographer Taylor Branch, was to launch a “Poor People’s Campaign” – a multiracial effort to eradicate poverty.

King’s model was The Bonus Marchers of the 1930s – World War I veterans who rallied in Washington, DC, to ask for help making the transition from the military to civilian life.

“The Bonus Marchers who went there didn’t convert the nation then. But 12 years later, people talking and thinking about this enacted the GI Bill for returning soldiers, which turned out to be, one of the greatest steps forward for [the American] middle class – for education, for jobs, for the American people,” Branch told Al Jazeera recently.

“[King] was hoping by analogy, the ‘Poor People’s Campaign’ would start working on the American psyche and would do something along the lines of the GI Bill to set that in motion,” he said.

“He was trying to present these issues and didn’t get that far.”

Branch, the Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer of King, and a co-executive producer of a new documentary on the last years of his life, King in the Wilderness, said King was driven in the last years of his life to help the US confront big challenges such as the war in Vietnam, racism and poverty.

His vision was controversial, said Branch. King’s fellow activists thought he was overextending himself.

So too, apparently, did many of King’s white supporters.

“The polls showed that even as early as 1965, most Americans were saying that in the polls that ‘black people have gone too far. We’ve given them a lot. We have given them the 1964 Civil Rights Act. We have given them the Voting Rights Act’,” Branch said.

“Already you were seeing the beginning of backlash psychology,” he added. “‘What about white rights? And anything you do from civil rights taking something away from me’.

“That politics was being cultivated, and is still being cultivated. I think we are in it today.”

Indeed, 50 years after King’s death, the city of Memphis and surrounding Shelby County are still facing the problems he was targeting.

A new report finds that black median income is still half of white median income – unchanged since 1968.

Twenty-nine percent of black people in Shelby County live in poverty, compared with 9.4 percent of white people.

A total of 48.3 percent of black children live in poverty, compared with 11.4 percent of white children.

What is more, a separate analysis says that of US cities with more than a million residents, Memphis is the poorest community and that every racial and ethnic group has seen its numbers of poor residents increase.

The challenge facing those commemorating King’s death is whether they can find the will to attack the causes of poverty, not just in Memphis, but across the US – and whether they will be able to report significant progress 50 years later.