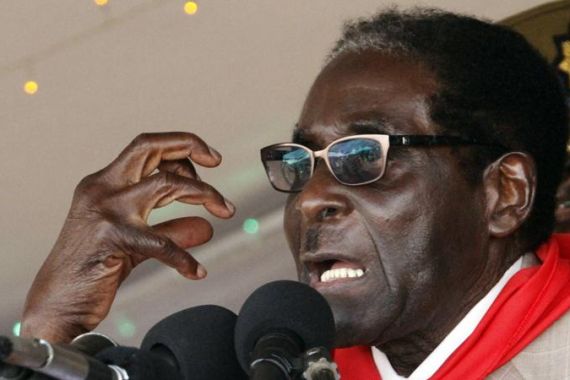

Zimbabwe braces for Mugabe surprises

Upcoming election could be the strongman’s last, and he has vowed to fight like a “wounded animal”.

The news didn’t come as a surprise, it was expected.

I was in Harare the day European Union countries made the announcement they were going to take only a few individuals off the sanctions list.

The sanctions were imposed in 2002, for what the EU called gross human rights violations in the country.

The state media was lambasting the EU and Western countries. It was as if Zimbabwe government officials felt insulted by the EU.

We heard the usual rhetoric from Zimbabwean politicians: “[T]he EU is racist, they want to punish us for our land reform programme….for our indigenisation policies…”.

Some politicians were livid because they believe Zimbabwe has tried to shed it’s bad image in the last five years. International journalists have been allowed into the country to work.

The government of national unity between President Robert Mugabe and Prime Minister Morgan Tsvangirai didn’t unravel, and political violence levels have gone done significantly since the contested 2008 election.

But the EU believes Zimbabwe can do more and has promised to review their decision if the country holds free and fair elections.

I met Rugare Gumbo at the headquarters of the Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) in Harare. He’s Mugabe’s party spokesperson.

He was literally shaking with anger, and that’s when I suspected ZANU-PF officials were going to retaliate.

A week later, Zimbabwe’s foreign minister, Simbarashe Mumbegegwi, voiced his belief that Western countries won’t be impartial if they send election observers for July’s presidential election.

ZANU-PF officials have said they will instead allow in election observers from the regional body the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the African Union, the trade group called the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, .

Independent election observers

Tsvangirai’s party, the Movement for Democratic Change and Western nations have said the only way Zimbabwe’s elections can be free and fair is if international observers are allowed into the country.

From previous experiences, however, once the decision is made not allow anyone in by ZANU-PF, it’s almost impossible to change things.

So what does that mean for international journalists hoping to cover what could be Mugabe’s last election?

It could mean people of specific nationalities won’t be allowed in. The only way into the country is sneaking in through one of the borders by road. Many have done it in the past. But if they get caught, they will be arrested.

I suspect officials will let in countries perceived to be friendly, for example Sweden, France, Canada and others.

That way they can try to claim they aren’t shutting out international media.

But it will, ultimately, be up to the SADC to expose any irregularities in the polls.

They have been criticised in the past of siding with Mugabe and ignoring glaring irregularities. It remains to be seen if will they be impartial this time around.

There is speculation among some political analysts here that if Mugabe wins the presidential election he may not want to serve a full five-year term. After all, he is now 89 years old.

As the independent newspaper, Newsday, wrote: “President Robert Mugabe says he now feels lonely both at home and in government as he is now surrounded by ‘small people’ he cannot relate with on an equal footing because of [an] age difference.”

Some Zimbabweans think their president may possibly step down and hand over power to the first vice president.

And, if this is Mugabe’s last election, what surprises does he have up his sleeve?

He’s said in the past he is going to “fight like a wounded animal” to win.

Interesting times are ahead for a country that was once the breadbasket of Africa. In recent times, it has had one of the highest inflation levels in the world, and now it’s trying to claw its way back into the international platform.