Book records Palestinian art history

In the process of seeking an alternative to the Zionist account regarding the creation of her own country, Israeli Gannit Ankori may have finally brought Palestinian art out of the shadows.

An associate professor of Art History at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Ankori has spent much of the past 20 years interviewing Palestinian artists with the intention of understanding the meaning and significance of their work.

After discovering their art had been largely ignored by the West, she became persuaded to amalgamate her research and is now publishing an English-language book devoted entirely to Palestinian art.

Her book dispels a commonly accepted myth that there was no art in Palestine prior to the creation of Israel and subsequently relays the significance of the 1948 Nakba (Catastrophe) on the development of the milieu.

It also explores the effects of other important events such as the creation of the Paltestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and the Palestinian intifadas (uprisings), while simultaneously taking an unprecedented look at persistent themes in Palestinian art.

Ankori is also the author of two books and numerous articles about Mexican artist Frida Kahlo and issues related to exile, hybridity and postcolonial identities. She is currently visiting associate professor at the Women’s Studies in Religion programme at Harvard University.

Aljazeera.net’s Ismail Elmokadem spoke to Ankori in Boston last week:

Aljazeera.net: You begin your book with an anecdote that signified the point at which you started to question the “Zionist Master narrative”. How did this lead to researching Palestinian art?

Ankori: I was travelling in a car from Jerusalem to the Galilee with an American journalist and a Palestinian writer to see a play by the Palestinian theatre company Al-Hakawati.

We had just passed Canada Park and the American asked: “What is this beautiful place?” I told him what I had been taught: “This is Canada Park, a wonderful place for picnics. The pine trees were planted as part of the Zionist ideology of making the desert bloom.”

The Palestinian responded: “Yes, this place, Latroun, is now called Canada Park. The trees were planted as part of the Zionist effort to cover up three Arab villages that were destroyed and depopulated after the war of 1967.”

|

“I was shocked… I realised that I had to actively re-learn the history of my homeland” |

I was shocked. I had no idea. As soon as we passed by Canada Park, I didn’t answer any more “American” questions. I realised that I had to actively re-learn the history of my homeland. My quest to understand Palestinian art was related to this journey and to my need to uncover the narratives that had previously been repressed and covered up.

This was in the mid-1980s and I found out – to my great astonishment – that there was virtually no research literature to be found on the subject, just a handful of articles mostly by artists. The only way to find out about Palestinian art was to embark upon primary research.

Were most Palestinian artists interested in contributing to your book?

All the Palestinian artists that I’ve been in touch with have been extremely helpful and generous in discussing their art and granting me permission to reproduce their work. My contacts with some of them have spanned many years by now and have developed into profound and meaningful friendships. The book itself is dedicated – as stated on the first page “to the Palestinian artists who inspired it”.

So, no opposition from Israelis?

On the Palestinian side – in two decades I have encountered opposition from only one individual. Most of the opposition has come from Jews and Israelis, usually people who couldn’t care less about art and culture, who attack me on issues of ideology and politics. They have called me terrible names and consider me a traitor.

It is very sad.

I have been brutally attacked by right-wing Israeli fanatics who dislike every aspect of my project: my friendship with Palestinians; my respect and empathy for their culture; my belief in the immense importance of their art and my attempt to listen and write about the narratives and meanings imbedded within it.

What is the significance of the 1948 Nakba in Palestinian art?

I do stress the Nakba – as a defining site of collective memory of great magnitude. The Nakba (literally: catastrophe).

The significance of the Nakba cannot be over-emphasised. It had a devastating impact on the developing art of pre-1948 Palestine. It also had a variety of influences on post-1948 culture and the continuous shadow of this traumatic “memory site” continues to effect second and third generation artists.

|

|

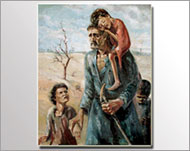

Ismail Shammout’s painting |

In Ismail Shammout’s 1953 painting Whereto?, the excruciating pain of exile that is expressed is based on Shammout’s own expulsion from Lydda in 1948.

Exiled artists were inevitably reacting to their new surroundings, responding to new cultural stimuli and to the influence of their host countries. Much of contemporary Palestinian art is therefore hybrid in nature – amalgamating native components with elements from the new environment.

You also make reference to events like the creation of the PLO in 1960 and the first intifada having an important effect on Palestinian art.

In the book I really try not to reduce artworks to mere illustrations of political milestones or events. Generally, though, after the establishment of the PLO images of fighters populate mainstream Palestinian paintings and posters. Before that – the images were mainly of refugees and of the lost homeland as an idealised object of desire.

The first intifada (December 1987) effected the art of several leading artists of the West Bank and Gaza. Artists like Sliman Mansour, Vera Tamari, Nabil Anani and Tayseer Barakat, for example, began to create from indigenous material in a more poetic and abstract vein.

|

|

Sliman Mansour’s Salma, 1984 |

I think the images of the uprising that were broadcast on TV made the overtly political paintings seem obsolete. The artists began to express their sense of identity or pain or rebellion in a more personal and less manifest manner. They said that in a sense the intifada also liberated them as artists.

In the 1980s I noted that many of the artists were using images that related to national identity that they had utilised before – the map of Palestine; embroidery; archaeology; calligraphy – but that instead of painting iconic images, they constructed collages, assemblages or earthworks composed of fragments of these elements.

The fragments conveyed a strong feeling of rupture and pain. Their collation into a work of art, however, also revealed a strong desire for healing and mending.

You also coined a new term in relation to Palestinian art – Disorientalism. What do you mean by this?

This neologism – with its deliberate phonetic and semantic ambiguities – was coined in the late 1990s and denotes my profound indebtedness to Edward Said’s theoretical insights concerning the Western construction of an imaginary orient.

|

|

Untitled by Raeda Saadeh, 2003 |

The implications suggested by this term are intentionally multivalent. They include the suggestion that the creation and study of Palestinian art entail the dismantling of an exclusively Western perspective, and the alternative, self-empowerment of oriental artists.

The term Disorientalism also alludes to a literal – ie geographical – “loss of the orient”. Hence, it is grounded in history and is linked to the exilic trauma of the Nakba.

Where do you think Palestinian art is headed?

Ironically, the tragedy of exile and dispersal has placed many Palestinian artists in an interstitial position between their oriental matrix and the dominant culture of the West.

From this “in-between” position, within a third space of hybrid creativity, Palestinian art has the power to undermine hierarchies, to invent new categories, to rupture the east-west divide, and to build bridges between cultures and peoples.

If we open our eyes and hearts – Palestinian art can show us what we need to see.

Artwork images published courtesy of Reaktion Books, London, 2006.