Coronavirus toll in New York City exposes wider inequalities

Geographic data shows a disproportionate number of low-income area residents suffering amid the coronavirus outbreak.

Under normal circumstances, low-income residents of New York City face heightened risks of economic dislocation, adverse health outcomes and workplace dangers. But in the age of the coronavirus, pre-existing inequalities are exacerbated by a disease that claims lives from all walks of life, but takes a far bigger toll on the less affluent.

Low-income areas in many United States cities tend to contain higher percentages of minorities. On a local level, maps of new cases call attention to the disproportionate number of people in working-class and deprived neighbourhoods suffering from the coronavirus.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsBoeing to offer staff voluntary layoffs, early retirement: Report

US Democrats mull next virus bill, Trump targets infrastructure

“In theory, while the virus is an equal-opportunity offender, the impact is certainly not going to be felt equally,” Ashwin Vasan, a public health expert at Columbia University told Al Jazeera. “We live in a deeply unequal society. And that plays out in every dimension of life.”

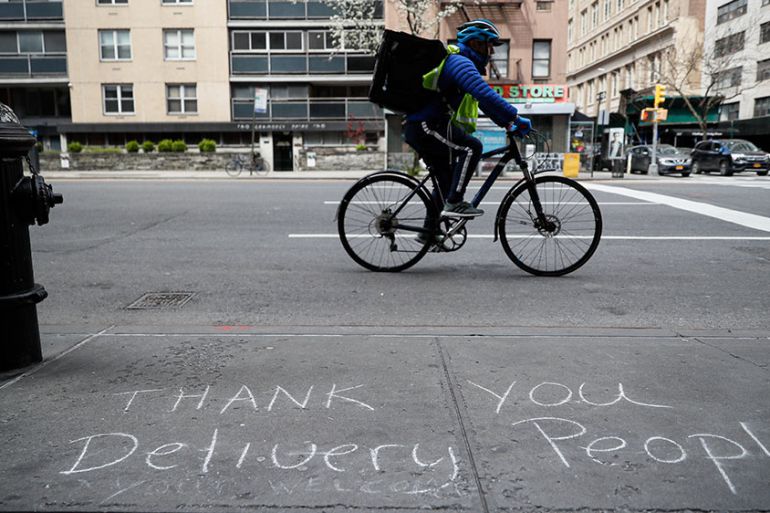

Members of lower-income communities are at greater risk of becoming hospitalised and getting even sicker, Vasan noted, because they often live in more crowded conditions. And many hold jobs that place them on the frontlines of the pandemic, such as warehouse workers for delivery services that have become a lifeline to millions of Americans under lockdown.

Low-income Americans are also more likely to receive insufficient medical care, while financial insecurity can multiply the negative consequences for households coping with the stress and strain of the coronavirus.

‘Endangering workers’

Labour strikes this week served as a stark reminder of the elevated risks faced by low-income, hourly wage earners, as well as health professionals on the front lines of the pandemic.

Workers with grocery delivery service Instacart and Whole Foods staged walkouts to protest against a lack of health protections. So did Bronx hospital nurses.

“People who have been underpaid for decades are now being called ‘essential’ employees,” Zach Lerner, the senior labour organising director at New York Communities for Change, told Al Jazeera, adding that they face an impossible plight of “having to worry about how to pay their bills and keep their families safe”.

Workers at an Amazon.com Inc distribution warehouse in the New York City borough of Staten Island walked off the job on Monday to demand that the facility be shut for two weeks for deep cleaning after employees had tested positive for COVID-19.

One of the strike organisers, Chris Smalls, was dismissed by Amazon, prompting New York City Major Bill de Blasio to order an investigation into the matter. Amazon maintains that Smalls was fired for violating social distancing guidelines and refusing to stay quarantined after being exposed to a colleague who had tested positive for the coronavirus.

Smalls issued a statement saying he would continue speaking up – despite being axed – for safety improvements “in the middle of the worst pandemic of our lifetimes”.

Dual health and financial threats

In the New York City metropolitan region, health equity experts say that African-Americans and Hispanics will disproportionately continue to wage an uphill battle against the twin scourges of physical and economic exposure to COVID-19.

Data released on Wednesday by city officials suggests that the virus has hit minority areas, many of which are populated predominantly by immigrants, especially hard.

Among the hotspots are parts of western Queens and the south Bronx – areas with the lowest median incomes in the city.

According to the Migration Policy Institute, “six million immigrant workers are at the frontlines of keeping US residents healthy and fed”.

Foreign-born Americans are over-represented in many professions, from physicians’ offices to food production. Mass layoffs have hit those sectors particularly hard, with the hospitality and restaurant industries among the most affected.

While the $2.2 trillion stimulus package includes individual cash payments for most Americans and enhanced jobless benefits that now extend to the self-employed and gig workers, many low-wage New Yorkers are still falling through that safety net.

Undocumented immigrants – and their spouses – are not eligible for stimulus payments, and even those legal immigrants who do file and pay taxes using an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number, or ITIN, instead of a social security number, will be ineligible.

Dawn Miller, a 56-year-old resident of the borough of Brooklyn, was laid off last month from her job in a college cafeteria. She has a pacemaker and cannot pay her rent. But she fears if she takes another customer-facing job she will greatly increase her risks of virus exposure.

“I’m scared to go out there,” she told Al Jazeera. “I live paycheque to paycheque, but I don’t want to take that chance right now.”

Miller has been unsuccessful in her attempts to secure state unemployment insurance money. And though she is spared from eviction temporarily, her housing situation is precarious.

|

|

‘Barriers to care’

A new Axios-Ipsos Coronavirus Index showed that many better-off white-collar Americans are still getting paid and able to work remotely from home, whereas many lower-income and blue-collar workers do not have that option. They are forced to risk exposure on the job or are sent home without pay.

A Pew Research Center study published last week found that Hispanics in the US are more worried than other groups about being sidelined physically and financially by the pandemic.

Many of the nation’s 60 million Latinos work in customer-facing leisure, hospitality and services industries. They are also less likely to have health insurance than other groups.

“Latinos are more likely to say they are concerned about the [impact of the] outbreak on their own personal health and finances than the US public overall,” Mark Hugo Lopez, Pew’s director of global migration and demography research told Al Jazeera.

According to Pew’s findings, some 50 percent of Hispanics surveyed see the disease as a major threat to their personal financial situation, compared to 34 percent of the overall public. Some 49 percent of Hispanics see it as a threat to the day-to-day life of their local community, compared to just 36 percent of the overall public.

Columbia’s University’s Vasan, who is also president of mental health nonprofit Fountain House, says that while the Pew findings found elevated anxiety levels among Latino communities, “the great unifier here is income level”.

“We’re going to continue to face vulnerabilities like this,” Vasan noted. “Whether Hurricane Katrina or Superstorm Sandy or earthquakes, they always end up falling down on the poor. This is an opportunity to reach into those cracks that are being exposed.”