China’s parliament: What it is likely to say about the economy

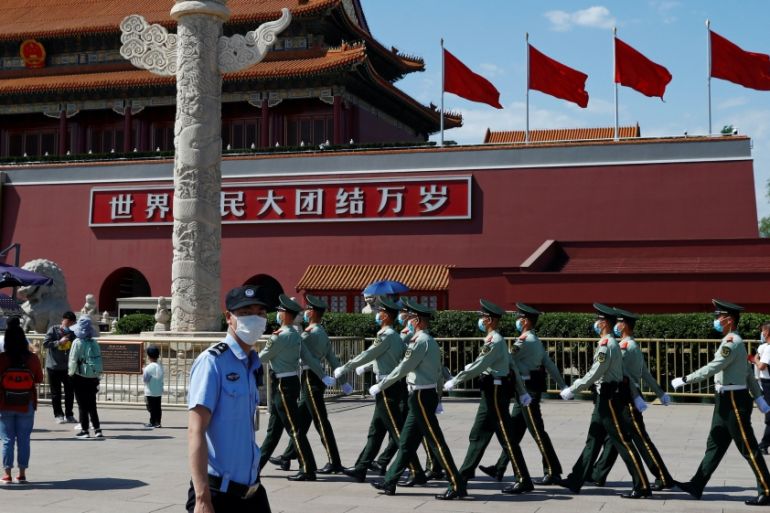

The National People’s Congress is due to unveil measures to cushion the economy from a historic virus-driven slowdown.

China’s annual session of parliament – or the National People’s Congress (NPC) – is hardly the world’s most exciting political event. In fact, it is usually highly predictable and frequently referred to as a “rubber stamp” of the Communist Party’s latest policy proposals.

The biggest issue facing the people and government of China this year is, of course, the coronavirus pandemic and the devastation it has brought to the country’s economy. And most of the policies being proposed will be aimed at protecting people and companies from the plunge in economic activity in the first quarter.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMexico’s teachers seek relief from pandemic-era spike in school robberies

‘A bad chapter’: Tracing the origins of Ecuador’s rise in gang violence

Why is the US economy so resilient?

One of the highlights of the NPC – which kicks off on Friday – in normal times is the government’s target for the growth in its gross domestic product (GDP), the most commonly used measure of economic activity.

So what is the government’s GDP growth target expected to be this year?

This is where things get interesting. Some economists say that because of the coronavirus, the government may abandon its growth forecast altogether.

“There is … a good chance that the government may drop a numerical GDP growth target for 2020, which would be the first time in two decades,” HSBC’s China economists said in a report to clients earlier this month.

Why is that such a big deal?

China’s central government uses its GDP growth target to determine a whole raft of economic policies, including how much to spend, what parts of the economy – be it helping the poor or building infrastructure – need the most attention, and which regions receive the most money.

When Premier Li Keqiang addresses the roughly 3,000 delegates at the congress – which has been shortened to about a week and delayed from March because of the outbreak – he would have to perform a delicate balancing act when it comes to proposing an economic growth target.

A target that is set too high would trigger a rush of spending by provincial officials to meet that goal, possibly raising debts to dangerous levels. If the target is too low, some could interpret that as an admission of failure.

Why would too low a growth target this year be seen as a failure of the government?

The pandemic could not have struck at a worse time for the central government in many respects. It had set itself the goal of doubling the size of the Chinese economy by this year compared with its level in 2010. But the closure of schools, factories, ports and the services sector between January and April has all but eliminated the possibility of it achieving that stated policy target.

Just how badly has the economy been damaged by the pandemic?

Figures released last month showed that China’s GDP shrank in the first three months of this year compared with the same period in 2019. That was the first contraction since China began releasing quarterly GDP data in 1992.

Never mind the government’s forecasts, what do other economists say China’s growth rate is likely to be?

The average of a poll of economists by the Reuters news agency last month showed private-sector economists expect China’s GDP to grow by 1.3 percent in the second quarter as shops, factories and offices slowly return to work. That would mean China will have narrowly avoided a recession, defined as two consecutive quarters of negative growth.

Over 2020 as a whole, China’s economy is forecast to grow by 1.8 percent, the poll showed. That would be the weakest annual performance since 1976, the final year of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, and less than one-third the 6.1 percent rate achieved in 2019.

Has the government ever missed its growth target in recent years?

Not really. This chart by Bloomberg shows that for most of the early part of this century, China’s growth rate far exceeded its own forecasts.

But much of that growth was funded by ever-larger amounts of debt, and it resulted in over-inflated prices of assets such as property, leading to a rise in inequality and the danger of social unrest. It was also largely fuelled by cheap exports, which angered its trading partners, most notably United States President Donald Trump who launched a trade war against Beijing soon after taking office.

So, over the last 10 years, China has tried to execute what economists call a “soft landing”, in other words, attempting to bring its growth rate down to more manageable levels without causing too much pain among people and companies.

So if the focus is not on GDP growth this year, what will dominate the NPC’s economic agenda?

“Beijing will likely emphasise the unemployment target this year, as it was added as a key target only in 2018,” writes Houze Song, a research fellow at MacroPolo, the in-house think-tank of the Paulson Institute in Chicago.

“Targeting employment rather than growth is a significant change, one that has been accelerated by the economic devastation from COVID-19,” says Song.

The urban unemployment rate stood at 6 percent in April, down slightly from the record high of 6.2 percent at the peak of the coronavirus pandemic in China.

The high level of unemployment is likely to have a continued effect on private spending and investment, Pauline Loong, managing director of research consultancy Asia-Analytica told Al Jazeera.

“As long as people feel that this virus is going to continue or that hasn’t been contained, there is very little in the way of stimulus that the government can do,” Loong said.

But even those figures could be understated. The Economist Intelligence Unit estimates unemployment could reach 10 percent this year, with about 250 million people experiencing wage cuts of between 10 percent and 50 percent.

What else is the government doing to boost the economy?

Alleviating poverty is likely to be another central theme of this year’s NPC. The government has set itself the ambitious task of eradicating absolute poverty – which it defines as people living on less than 2,300 yuan ($324) per year – by the end of 2020 and becoming what it describes as a “moderately prosperous nation”.

“China is determined to complete the world’s biggest poverty-relief project as scheduled,” the official Xinhua news agency said in a commentary last month.

Beijing is also trying to stimulate growth by spending heavily on infrastructure. But this does not just involve roads and railways. The government’s so-called “New Infra” plan would see it expanding its 5G mobile phone networks, building a large data centre and electric car charging networks, and investing in artificial intelligence among other hi-tech projects.

Some analysts have their doubts about these plans.

“Frankly, elements in the ‘New Infra’ scheme are not brand new, with the exception of the big-data centre project,” says Iris Pang, chief economist for Greater China at Dutch bank ING in a research note. “The big-data centre idea seems to have emerged from the COVID-19 crisis, with many office workers forced to work from home.“