Actinoform clouds revealed

A look at a cloud only revealed by viewing from outer space.

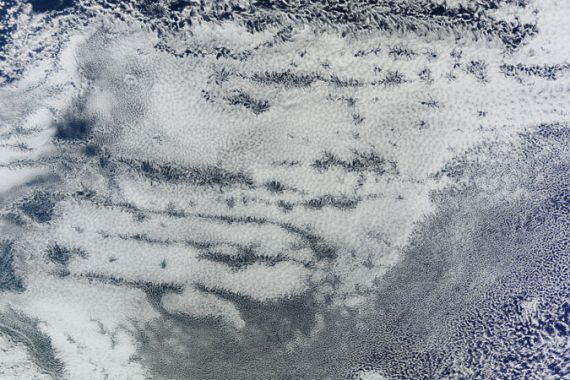

Actinoform cloud captured by NASA’s Terra satellite off the coast of California. [Nasa]

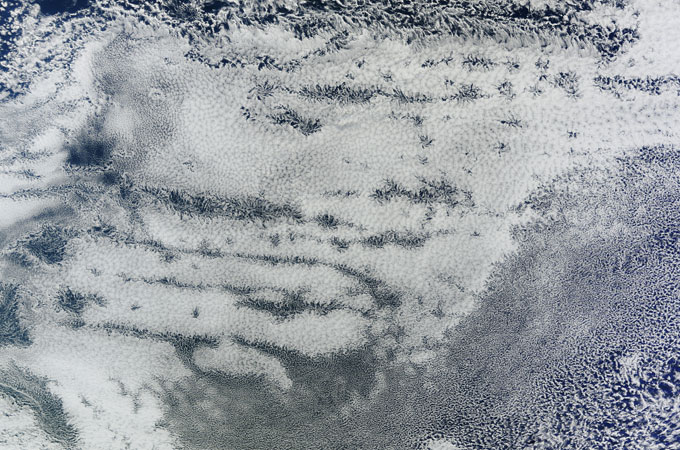

Actinoform cloud captured by NASA’s Terra satellite off the coast of California. [Nasa]

When the British chemist and amateur meteorologist, Luke Howard wrote his Essay on the Modification of Clouds in 1803, it soon became accepted as the cloud ‘bible’.

Howard’s system was based on a lifetime of careful observation. He identified three main categories – cumulus, stratus and cirrus – based on their perceived characteristics. Cumulus clouds are lumpy, like cauliflowers; stratus are layered; cirrus are wispy.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsAfter the Hurricane

World’s coral reefs face global bleaching crisis

Why is Germany maintaining economic ties with China?

He refined his classification to accommodate transitions between the clouds – cirrostratus, stratocululus etc and he introduced etages: ‘high’, ‘medium’ and ‘low’ cloud heights.

Until the 1960s, Howard’s classification held good. In total, there were nine of each etage, making a total of 27 cloud types. Supplementary features were also identified, such as precipitation streaks ( virga) and undulations (mammatus).

In recent years our way of looking at clouds has changed. As weather observations on the surface of the earth become increasingly automated, visual observations are increasingly becoming the preserve of the ever more sophisticated satellite systems orbiting the globe.

Since the first Tiros satellites began sending back grainy, black-and-white images in the early 1960s, it has become apparent that our weather systems are much more complicated than previously thought.

Instant occlusions, comma clouds, conveyor belt theory all came about as a way of explaining the strange shapes and patterns revealed by satellite imagery.

It is the same with the clouds themselves. The image above is of actinoform clouds, first identified in the 1960s.

Even as recently as 2000, the clouds were not included in the Glossary of Meteorology which is considered to be a definitive reference work.

This may be because it was thought that actinoform clouds were simply stratocululus clouds undergoing a transition from an ‘open cell’ to a ‘closed cell’ structure. (‘Open cell’ clouds look like an empty honeycomb whereas ‘closed cell’s look like the compartments have been stuffed with cloud.)

Certainly, viewed from below, they do not display the distinctive radial structure observed from above. (Actino derives from the Greek word for ‘ray’.)

Research is still being carried out on these clouds but they are common off the western coasts of continents, particularly Peru, Namibia, Western Australia and Southern California. In these regions cool ocean waters are overlain by areas of high pressure.

This limits convection but when the clouds show the presence of actinoforms, there is an increase in drizzle. The link between actinoforms and precipitation is still being studied but they may play their part in ‘May Gray’ and ‘June Gloom’ weather patterns in California.

Whatever the mechanism for their formation there is no doubt that satellite images have revealed a truly distinctive and fascinating type of cloud.